Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: December 10th, 2019 in Wetland Restoration

By Clare Sevcik, DNREC’s Nonpoint Source Program

Riparian buffers are planted areas specifically next to waterways, such as streams, ponds, wetlands, and rivers. These areas are extremely important to keeping our waters healthy. They do so by filtering and trapping nutrients and sediment out of waters before they enter our local waterways.

Different types of plants can be found in buffers, ranging from grasses to mature trees. The type of plants present in the buffer has an effect on how it may function.

Usually, riparian buffers are classified into two types, grass or forest. As the name suggests, grass buffers are dominated by grasses. Grasses are tremendously effective in slowing down the flow of water, but are still not as efficient as our next buffer type in improving water quality and quantity.

Forest buffers are dominated by larger plants, such as shrubs and trees. Planted forested buffers are usually made up of a variety of species that will grow to different heights to recreate a natural forest. These plants are bigger, therefore hold onto more water and have more water processing ability. One thing to note is that the type and placement of each tree requires a lot of forethought and planning to make sure the buffer is successful.

Buffers serve a number of important roles in the ecosystem. First, they are a waterway’s first defense against runoff. As rainwater flows across the land, it picks up various pollutants. Buffers help by slowing down this water, giving plants a chance to remove pollutants, such as sediment and nutrients, and allowing the water to seep into the ground. Excess nutrients in waterways can be a huge issue because it can cause algae to bloom and wreak havoc on the water quality in a process called eutrophication.

In a heavy rain event, unprotected and unsecured banks can erode due to flooding and runoff. Both types of vegetated buffers help maintain shorelines by stabilizing the banks and holding together the sediment. Forest buffers especially boast large root systems that can hold sediment extremely well once the plants are established. These root systems are able to hold onto the sediment and prevent the flooding from carrying it further downstream.

Lastly, forest buffers are also important to support local wildlife and a healthy ecosystem. Most waterways benefit from shade from established trees with a good sized canopy along the bank. This shade helps to regulate the water temperature, preventing the water from warming excessively, as warmer waters may encourage large algal blooms and cause unnecessary stress for fish and other aquatic organisms. The root systems from these trees can also provide nursery habitat and shelter for animals.

Riparian forest buffers provide more benefits and protection for waterways than grass buffers, so many states are looking to implement these as best management practices (BMPs) to improve water quality. For example, about a third of Delaware is located in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. Therefore, Delawareans in that 1/3 of the state have an impact on the Chesapeake Bay. Installing riparian buffers in these areas can help Delaware meet its goals for reducing pollution to the Bay, which is a beautiful and vital resource in the Mid-Atlantic region.

Delaware is among six Chesapeake Bay Watershed states – along with Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York – and the District of Columbia committed to a federal-state initiative to develop a pollution “diet” that will help restore the water quality of the Chesapeake Bay and its tidal waters by 2025.

All of these states are working to improve the Bay’s waters by implementing projects, or Best Management Practices (BMPs), throughout the watershed. Delaware’s most recent, and final, strategy for implementing BMPs can be found in Delaware’s Chesapeake Bay Phase III Watershed Implementation Plan (WIP). In addition to implementing BMPs, Delaware has committed to a wide array of goals and outcomes that were outlined in the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement.

Because Delaware signed onto the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement, the State has been specifically designated federal funding to help meet Chesapeake Bay goals. These funds are categorized into two grants, the Chesapeake Bay Implementation Grant (CBIG) and the Chesapeake Bay Regulatory and Accountability Program (CBRAP).

The CBIG focuses on funding projects consistent with the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement goals and outcomes: sustainable fisheries, vital habitats, water quality, toxic contaminants, healthy watersheds, stewardship, land conservation, public access, environmental literacy, and climate resiliency. This grant is awarded based on Request for Proposal submissions to DNREC’s Nonpoint Source Program.

The CBRAP grant focuses on implementing and expanding their jurisdictions’ regulatory, accountability, assessment, compliance, and enforcement capabilities in support of reducing nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment loads delivered to the Bay to meet the Water Quality Goal of the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement and the Bay TMDL.

Different federal funding sources are also available to cost-share other BMPs. In particular, the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP) focuses on the agricultural sector, and offers incentive payments to landowners in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed portion of Delaware to implement BMPs. There is a particular focus on creating new or improving existing forested buffers on their properties.

If you are interested in learning more about buffers and the grant programs please contact Brittany.Sturgis@delaware.gov (CBIG), Sara.Wozniak@delaware.gov (CBRAP), or Patti.Webb@delaware.gov (CREP).

Written on: September 16th, 2019 in Living Shorelines

By Chris Pfeifer, Cardno

On a warm July morning not long after the official start of summer, some 2 dozen volunteers gathered at Sassafras Landing, an unimproved boat launch popular with kayakers and duck hunters inside the Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife’s Assawoman Wildlife Area (AWA) near Frankford. Their mission: transplant nearly 5,200 plugs of native marsh grass onto what otherwise appeared to be a pristine white sand beach. The efforts that day were the final phase in constructing a living shoreline, and the culmination of more than a year’s worth of planning and design by a multidisciplinary team of scientists and engineers from the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC), the Delaware Center for the Inland Bays, and Cardno, a local consulting firm.

Nearly a year before, members of the design team waded along this very shoreline. What they encountered, unfortunately, was all too common in Delaware’s Inland Bays. Along most of the shoreline, ragged undercut banks choked with Phragmites were all that remained of the fringing salt marsh that once occupied the transition zone where land meets water.

Over time, most of the Spartina alterniflora, the dominant plant species of Delaware intertidal salt marshes, had been whittled away by erosion. Analysis of aerial photos confirmed the loss of about 11 feet of fringe marsh from this shoreline between 1992 and 2017. That’s about a ½ foot per year on average. It may not sound like a lot, but inches add up over time.

Salt marshes play an important role in combating shoreline erosion and protecting adjoining uplands. The leaves and stems of marsh grasses absorb and dissipate wave energy, while the dense, intertwining roots help bind the soil. Although marsh loss due to erosion is never a good thing, wider marshes can withstand the damage without sacrificing too much of their protective function. But narrower marshes, like at Sassafras Landing, are less able to sustain the loss. And in some places, the stakes are higher than others.

Such is the case at Sassafras Landing where the ever-narrowing marsh fringe helps protect and maintain an important feature just landward of water’s edge: a low berm of mounded soil constructed decades ago to separate the tidal waters of Miller Creek from 35 Acre Pond, one of five non-tidal freshwater impoundments within AWA managed for wildlife and ecological diversity. In the narrowest part of the berm, hastily piled rocks line an indentation in the shoreline; a stop-gap to repair erosion from a coastal storm that almost breached the berm several years ago and an ever-present reminder of the ongoing threat from shoreline erosion.

It was clear to the team that something was needed to address the shoreline erosion, but what? As a partner in a statewide initiative to increase awareness of alternatives to traditional “hard armoring” practices like riprap and bulkhead, the Delaware Center for the Inland Bays selected Sassafras Landing as a living shoreline demonstration project.

The term “living shoreline” refers to a suite of shoreline stabilization and erosion control techniques that use natural materials like wetland plants, oyster shells, and coconut fiber “biologs” to repair damaged shorelines and increase their resiliency to the adverse effects of erosion and sea level rise. Sometimes more structural components like rock are used in combination in what’s known as an “armored living shoreline.” Regardless of these variations, all living shorelines seek to sustain, enhance or restore ecological functions and maintain or reestablish connections between uplands and aquatic habitats across their natural gradients.

After evaluating several different living shoreline techniques in relation to site conditions and project goals, the design team selected an armored living shoreline treatment known as a rock toe sill. This treatment consists of a linear arrangement of free-standing rocks (the “sill”) just offshore parallel to the eroding shoreline. The area between the toe sill and the shoreline is then backfilled with clean sand, graded to appropriate elevations, and planted with native vegetation to create or restore a protective marsh fringe.

Information about parameters like shoreline orientation, topography, fetch, tides, wave energy, and water depths were gathered through a site evaluation process and then used to refine the conceptual design. After several iterations, the design was finalized. It included 5 segments of low-profile rock toe sill spanning just over 400 linear feet. Taking sea level rise into consideration, each sill is between 7-8 feet wide at its base and 2-3 feet tall, putting the top of each sill 6 inches above the average water level at high tide. Since only the highest high tides will overtop the sill, 5-foot gaps were included between each segment to allow for tidal exchange and passage of aquatic organisms. The western ends of all but one sill flare outward to shield the gaps from exposure to the northeast, the direction of the most powerful storm-driven wind and waves, and the longest fetch. As added protection, mesh bags containing oyster shells line the inside of each opening to help absorb wave energy and retain fill.

Once the design was finalized, permit applications were submitted to DNREC’s Wetlands and Subaqueous Lands Section and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Due to the amount of fill required, the project did not qualify for DNREC’s Statewide Activity Approval for living shorelines, and instead received an individual subaqueous lands permit. Authorization from the Army Corps was granted under Nationwide Permit 27 for Aquatic Habitat Restoration, Enhancement, and Establishment Activities.

Funding for project construction was received through the 319 Nonpoint Source Program Grant and in-kind contributions from several of the groups involved. Construction of the toe sill, backfilling, and grading were all performed in-house by the Division of Fish & Wildlife’s Little Creek construction crew. Staff from AWA, Cardno, and Delaware Center for the Inland Bays oversaw the construction activities.

Earthwork was initiated in early June and was completed over the next four weeks. Which brings us back to where we started. As the final step, nearly 5,200 plugs of three different species were planted in zones according to their hydrologic preference. Spartina alterniflora, known commonly as smooth cordgrass, was planted at the lowest elevation. Spartina patens (saltmarsh hay) followed higher on the shoreline, above the level of daily tidal inundation. Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) was mixed in at the highest elevation where the new shoreline meets the berm.

Just two short months after completion, the Sassafras Landing living shoreline is indeed coming alive. Aside from a few dead or missing plugs, which is to be expected, the planted grasses are thriving. Although individual plugs are still recognizable up close, even from a short distance away, the shoreline is beginning to take on a more and more natural appearance.

Schools of small fish abound in the quiescent water landward of the sill along with a handful of blue crabs. Though the new living shoreline has yet to be tested by tropical storm or nor’easter, we remain ever hopeful that the efforts of this spring and summer, and the planning and design that preceded construction, are the beginning of a new chapter for this little piece of shoreline and the valuable habitat it protects.

The completed Sassafras Landing living shoreline project after Hurricane Dorian passed and brought high water levels in August of 2019.

Written on: September 16th, 2019 in Education and Outreach

By Erin Dorset and Kenny Smith, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

If you spend a lot of time traveling around Delaware, you’ll notice that northern Delaware is very different from the rest of the state. That’s because Delaware is made up of two distinct geologic regions. The northernmost part of Delaware is within the Piedmont region, while the rest of Delaware lies within the Coastal Plain region.

The Coastal Plain is relatively flat and is characterized by small hills, gradual slopes, and sandy or silty stream beds. In contrast, the Piedmont region tends to have bigger rolling hills, steeper slopes, some small cliffs, and stream beds with more rocks, much like a lot of Pennsylvania.

Landscape characteristics play a big role in determining what kinds of wetlands occur in different areas. So, there tend to be differences in the wetlands in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions. Through our years as wetland scientists, doing fieldwork all over Delaware, we have made some first-hand observations about wetlands in these two geologic regions. For example, we have seen that flat wetlands are one of Delaware’s most common wetland types in the Coastal Plain, yet they are fairly uncommon and often smaller in size in the Piedmont because of more varied terrain.

Another observation that we’ve made is that riverine wetlands are often larger in the Coastal Plain. Streams and rivers in that region typically have gradual banks, allowing water to easily overflow into floodplain areas. In contrast, riverine wetlands that we’ve seen in the Piedmont region are often smaller, and many waterways do not have any riverine wetlands along them at all. This is because stream banks tend to be higher and steeper, and streams are often found at the bottoms of slopes, so flood waters do not cover as much land when the banks overflow. The slope of the land also tends to drain water off more quickly, so floodplain areas may not stay wet for as long.

Yet another thing that we have noticed is that seepage wetlands are more common in the Piedmont region than in the Coastal Plain. Seepage wetlands are wetlands formed in places where groundwater comes out onto the surface year-round or nearly year-round. Some of them are closed-canopy seeps, meaning that they are within the forest and create the headwaters of some streams. They are usually dominated by skunk cabbage and are small and narrow in size and shape. Others are open-canopy seeps, which are wet meadows fed by closed-canopy seeps. These have few trees and shrubs and a wide variety of herbaceous plants. Seepage wetlands tend to form at the bases of slopes, which is why they are prevalent in the Piedmont region and are not as common in the Coastal Plain.

Curious about making some of your own observations? Check out some of these parks and forests that will let you compare and contrast the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions of Delaware!

Written on: September 16th, 2019 in Wetland Assessments

By Samantha Stetzar, University of Delaware

Wetlands work is not for the faint of heart. I won’t sugar coat it for you. Its dirty. Its messy. Oftentimes pretty buggy (even though we really lucked out this year). Yep. Wetlands can be all of those things. But – they are also so much more. I don’t think I’ve learned so much in one summer than I did working as a seasonal with DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment team.

This year we focused primarily on wetlands in the Brandywine Watershed, or rather, the Piedmont region of Delaware. Since this watershed was so unique in that it contained elevation, topographical configuration allowing for seep wetlands to emerge, I got a closer look into how the protocol is adapted and modified. Due to the unique topography of the region, assessing these wetlands became more of a challenge in comparison to previous watersheds in relatively flat locations of Delaware. However, I welcomed the challenges!

Each and every site was a new adventure, whether it be trudging through an abandoned town – turned mitigation site to discover the most strangest depressions, or practically clawing our way up cliff-sides I never would have imagined existed in Delaware, and even trekking across a railroad bridge suspended 30 ft above a shallow creek . No matter what obstacle stood in our way, I was eager and ready. Through the whole summer I truly felt like a contributing member to part of a team working towards a goal much larger than ourselves.

I didn’t realize until a week out of the job just how much of a profound impact this position had on my outlook on life. I’ve become more positive, patient and resilient. Not to mention the amount of knowledge I’ve learned from the many experiences and my amazing team members. By the end of the summer I find myself stuck in permanent “wetlands detective mode”, constantly surveying the landscape for indicators of wetlands and quietly naming off species within the local plant communities (thanks for the help with scientific names!). But this has something to say about DNREC’s wetlands team and phenomenal monitoring and assessment program.

This position was as much as a learning experience as it was a job; and I’ve left with so much more than when I started. I only hope more people will have an opportunity to realize the amount time and hard work wetland scientists dedicate to protecting Earth’s remaining wild spaces.

It’s important that we continue to assess and monitor the remaining wetlands that we have in order to ensure their existence for future generations to come. So I urge you, if you ever do get a chance to go out with a wetlands scientist, dive right in, no questions asked – just make sure you have hip-waders on first! Not only will you return with a myriad of knowledge and a renewed sense of appreciation for the natural world, but the satisfaction of a hard day’s work. So get ready. It’s time to get comfortable with being uncomfortable!

Written on: September 6th, 2019 in Wetland Assessments

By Christina Whiteman, DNREC’s Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve

When a power company needed to replace a utility pole in a saltmarsh, staff at the Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve (DNERR) jumped at the opportunity to work closely with the power company and other state agencies to study how the marsh would recover naturally from this man-made disturbance.

The DNERR is one of 29 reserves across the country and was established in 1993 as a cooperative program between Delaware’s Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. It is comprised of two components: the Blackbird Creek Reserve in Townsend and the St. Jones Reserve in Dover. The Reserves are also used as reference sites, habitats that are unaltered or close to their natural state, by DNERR and other organizations to study the impacts of climate change.

At the DNERR, the Research and Stewardship programs work together to understand how the marsh changes over time through long-term wetland vegetation monitoring (i.e. we get nerdy with some plants and mud). One of the reference sites in the DNERR Biological Vegetation Monitoring Program, is at the St. Jones Reserve along the St. Jones River. The vegetation monitoring that takes place here is part of a nationwide effort within the National Estuarine Research Reserve System, where numerous long-term datasets are collected on water quality, wetland plants and surface elevation tables.

In 2013, DNERR was notified that there was an emergency pole replacement project that needed to be implemented to prevent a leaning power line from collapsing, but the proposed project went through the DNERR Biological Vegetation Monitoring Program site. In order to ensure that the power lines were replaced in a way that would prevent long-term datasets from becoming compromised, DNREC and the power line company went to work.

The collaboration resulted in an installation method that would reduce harm to the marsh, while also maintaining the integrity of the long-term datasets. In 2015, the power lines were replaced using a helicopter to install the poles at each location, instead of using heavy machinery across the marsh. To help the construction workers get around, an airboat and amphibious tracked vehicle were used to transport them to each pole.

One of the interesting outcomes from the planning process was that the emergency pole replacement project presented a unique opportunity for the DNERR to study resiliency of wetland ecosystems to low impact construction within a closely monitored area.

After the project was completed, the DNERR was interested in understanding how wetlands naturally recover over time without human interference. Since the DNERR has an established protocol for monitoring wetland plants, this protocol was used to begin a monitoring project in the construction area.

Photo documentation was added to the monitoring protocol to visually understand how landscapes change or recover. Some areas of the power line replacement monitoring project have changed to provide new habitats that didn’t exist before. For example, in areas that were heavily trafficked during the construction efforts, mudflats with dense wetland plants on the edges have created foraging habitat for marsh birds.

Another thing we learned is that areas where the wetland plants have recovered did not have many small streams or channels. Other areas that changed and have not recovered as quickly all had significant water flow in the construction areas.

Lesson learned: if there is a need for construction in the future, it might be a good idea to avoid or maneuver around streams or channels to minimize impacts to the wetland.

Although the DNERR has been monitoring this area for four years, there is still a lot of information that can be collected to understand how the marsh naturally recovers over time. It will be interesting to see how this area looks in the future, and that’s one of the fun parts about science!

For more information about this project, please contact Christina.Whiteman@delaware.gov.

Written on: May 15th, 2019 in Education and Outreach

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

In our Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program we speak so often about the ecosystem services that wetlands provide or the beneficial functions wetlands perform daily. We rattle them off in varying order “provide vital habitat for plants and wildlife, improve water quality, protect our coasts, act like a sponge to store floodwater, sequester Carbon from the atmosphere”.

We do this so often, that sometimes we forget to take a step back and explain what exactly we mean and how exactly wetlands work. For example, how can a wetland clean water?? Wetlands are muddy and sometimes stinky. How on earth could a wetland clean my water?

Wetlands are magicians. In their own, natural, wonderful form, they magically filter out and pull aside an assortment of nasty stuff that you and I don’t want in our streams, bay and ocean, or as we kayak and fish.

What can wetlands help filter out from our waters, you might ask?

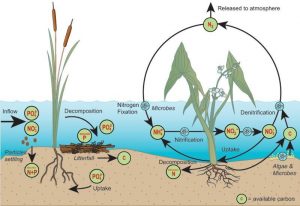

A magician rarely reveals their secrets, but in this case we’re spilling the beans. Wetlands remove nutrients through a combination of complex physical and biological processes. Let’s break it down (pun intended)..

Wetlands are like sponges and are great areas for holding onto water. They are also areas where the speed of water flow is drastically reduced and sometimes even stands still. As the water sits in the wetland, nutrients can be removed from the water in a couple of ways: they can simply sink down and settle on the soil surface, be released into the atmosphere or be trapped in the soil as the water filters its way slowly down through the ground.

As you can see, soils play an important role in this physical process. One of our favorite marsh metaphors to use in presentations is that wetland soils are like a strainer or sieve. We hold up a pasta strainer and kids look at us like we’re crazy but really, it fits. Just like the strainer, wetland soils have lots of tiny holes, nooks and crannies (think English muffin) to trap impurities and toxins. This process allows the cleaner water to continue on through, entering the stream or bay or even our underground aquifers.

There are also biological processes occurring in wetlands that can help to clean our waters. Plants, algae, and bacteria can use and transform nutrients that have sunk onto and in the soil to grow big and strong and create future generations.

Bacteria (or microbes) are really neat organisms that do some fancy biogeochemical processes called nutrient transformations. Ammonification, nitrification and denitrification are examples of nutrient transformations that turn not-so-great chemicals into less harmful ones or into a useful nutrient for plants. All of these processes are facilitated in many places throughout a wetland.

Healthy microbes also need a good source of carbon for their growth and energy and wetland plants serve as a key source of carbon! So the take home message is that these bacteria rely on wetland plants, and a wetland planted with lots of native plants (as opposed to an open pond) is going to be capable of the most nutrient transformation.

If you’re thinking that this is interesting but doesn’t affect me, you might be surprised to learn that approximately 25% of the State of Delaware is made up of wetlands, and that from where you are reading this right now, there is probably a wetland within a mile of you. This means that a wetland is hard at work for you right now trying to keep up with all the demands we place on them.

There are a few things you can do to lighten their load, so to speak.

Let the magician put on a show uninterrupted and we can all enjoy cleaner, healthier waters!

Written on: May 14th, 2019 in Wetland Animals

By Clare Sevcik, DNREC’s Nonpoint Source Program

There are so many charismatic animals that make Delaware waterways their home. Most people living in Delaware can easily recognize a few of the most popular species: bald eagles, osprey, blue crabs, horseshoe crabs, beavers, river otters, and many more. But there are many more animals living below the water’s surface that are incredibly important to the area’s ecology. One of these lesser known animals are the freshwater mussels.

Freshwater mussels are bivalve mollusks that live along the bottom of rivers, streams, and lakes in softer substrates like sand. They can live for a very long time and, in a healthy environment, some species can live to be 100 years old!

North America is also home to the most species of freshwater mussels in the world. Around 300 species live here. Worldwide, there are about 1,000 species. So, we are home to almost 1/3 of the world’s species. Most of those are found east of the Mississippi River, too.

Freshwater mussels have an unusual life cycle. Before they settle and become the slow-moving bottom dwellers we all picture, they are very mobile and hitch rides on the gills of various fish. For the first portion of their lives, they’re parasites.

Female mussels internally fertilize their eggs with the sperm of nearby males. Once fertilized, she releases the larvae (called glochidia) as migrating fish pass by. The glochidia are attached to the fish’s gills until they are large enough to survive on the stream bottom, which may be far away from their parents since fish can travel great distances and against currents. Mussels depend on these fish and each mussel species relies on different fish species to host their young.

Interestingly, freshwater mussels aren’t eaten by humans, like their saltwater relatives. Native Americans used to supplement their diets with mussels, but nowadays we have many more protein options. Freshwater mussels aren’t as tasty as their saltwater counterparts and can often be full of pollutants and/or parasites that have bioaccumulated over their lifetime of filter feeding.

Most species are also classified as endangered or threatened and cannot be collected. Instead, they are eaten by raccoons, muskrats, river otters, fish, and turtles. But they serve a much more important ecological function than just being food.

Mussels are incredibly efficient water filters! A single mussel can filter through approximately 20 gallons of water per day. Why do they filter so much water? Mussels are filter feeders and comb the water for food, such as algae, bacteria, and small, microscopic plankton. While doing so, they reduce the amount of sediment and other nutrients in the water.

Even though they are such productive water filters, freshwater mussels are very sensitive to the quality of their environment. They cannot survive in waters that are heavily polluted or in areas with erosion and sedimentation issues. Thus, mussels are more likely to be found in cleaner waterways that are not overwhelmed by pollution, runoff, or erosion.

Their sensitivity to water quality also makes them great bioindicator species, as they can only survive in healthier waters. A bioindicator species can tell researchers how healthy a waterway is based on their presence or absence.

Due to many factors, freshwater mussel populations have been declining, and approximately 70-80% of North American species are considered endangered. They are threatened by poor water quality and reduced access to their fish hosts. Dams prevent fish from traveling upstream, so some mussel populations have been effectively cut off since without hosts young mussels wouldn’t be able to survive in the water column.

But even if their hosts are available, the areas suitable for mussel survival are scarce. So once they detach from the host’s gills, they can’t survive in those areas. Mussels have also been affected by invasive species, such as zebra mussels and Asian clams. These invasives tend to reproduce quickly and overpower local mussel populations.

A LOT! Various nonprofit organizations and state agencies, such as our program within DNREC, have been actively trying to monitor mussel populations and improve local water quality.

The Partnership for the Delaware Estuary (PDE) has an extensive program in place to try to monitor and restore native mussel populations to the Delaware River, Susquehanna River, and their tributaries. PDE plans to open a freshwater mussel hatchery in southwest Philadelphia in 2023. The hatchery aims to produce 500,000 mussels per year to reestablish populations.

Additionally, dams in Delaware are slowly being removed and allowing fish to freely migrate through waterways, which will reconnect isolated populations and introduce glochidia to new areas.

Even with all of those programs and actions in place, native freshwater mussel populations will take a long time to recover, especially species that grow slowly. So we have to try to expedite their recovery by improving water quality as soon as possible!

There are many things you can do, regardless of where you live, to improve local water quality. Reducing fertilizer use, installing rain gardens and buffers, and even picking up trash can help reduce water pollution. For more information on how you can help improve local water quality, check out the Delaware Watersheds and Livable Lawns websites!

Written on: May 14th, 2019 in Wetland Assessments

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

In 1998 the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control’s (DNREC) Environmental Scientist, Amy Jacobs (now with The Nature Conservancy), took part in a grant project held by the Delaware chapter of The Nature Conservancy and the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. This project developed the science and comprehensive hydrogeomorphic models for freshwater wetlands in the Nanticoke River watershed and assessed water quality benefits of wetlands in varying condition. This was done to develop a wetland profile for wetlands in that watershed.

Then, in 1999 DNREC addressed the need to track not only the acreage of wetlands across Delaware and how that acreage is changing over time, but also examine the on-the-ground condition of wetlands. Measuring wetland condition compared to reference condition (the best and healthiest wetland you can find) gives a measure of how well wetlands are able to perform their natural functions and benefits.

Are our wetlands capable of trapping carbon, of intercepting and filtering pollutants from our surface waters, of holding stormwater and preventing flooding? These free benefits were underappreciated and not well tracked. If we can rate and track wetland condition as it relates to wetland function, we can grasp where wetlands are thriving and where they need work. Thus began the mission of the Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program (WMAP)!

Since then we have been building and growing! Our program has (with some partner collaboration) created 4 standardized wetland assessment protocols that rate wetland health, function and features. Working watershed by watershed we have visited nearly every corner of Delaware on the ground (12 watersheds).

This summer we will be working in the Brandywine Creek watershed which leaves only the small Pocomoke River still to visit. Over that time we have visited and assessed 1,420 random wetland sites across the state. With the help of willing landowners we have been able to access public and privately owned wetlands, allowing us to accurately rate wetland health statewide.

Along the way we met and worked with roughly 20 young professionals who joined us as seasonal wetland field technicians, assisting us during the busy summer season. Fieldwork is an adventure for everyone involved and we enjoy making memories and sharing our passion for wetland science with young minds.

It is so exciting the see how the Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program has grown over the years. Growing out of a research study with The Nature Conservancy, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, and Environmental Protection Agency, the program has held firm to using science as their foundation to improve management and educate a wide diversity of audiences. – Amy Jacobs, The Nature Conservancy, reflecting on where the program started two decades ago

Because unused data is wasted data we try our best to share our work and our information with the widest audience possible through every means we can. Over 20 years we have amassed thousands of photos, thousands of points of data and the most comprehensive tidal and non-tidal wetland condition dataset in the Mid-Atlantic Region.

Over the years we have gotten better at communicating wetland science and findings to an audience that isn’t always wetlands savvy. We’ve asked, we’ve survey and we’ve listened to what is important to Delawareans and how we can inform them to improve wetland protection and conservation.

Our program has been extremely fortunate to receive funding that allows us to continually grow and develop our program, addressing new needs as they arise. In 2008 we added a team member to focus on outreach and education which enables us to share our projects and results with many audiences online and in-person. We continue to expand our audience every year and we now average 3,500 in-person interactions per year through presentations, workshops, and exhibiting at events.

As times change so have we to reach a wider audience. In 2011 we established a Delaware Wetlands Facebook page which has accrued 2,000 followers. In 2014 we started an Instagram account which now has 1,200 followers who get to enjoy pictures of our adventures and mishaps in the field. Additionally we decided to start making short educational videos, which are great for anyone teaching about wetlands. This really pushed us out of our comfort zone! We have now starred in 14 videos which have 44,000 views.

Over the course of our program our staff has given approximately 275 professional presentations to audiences around the country (and internationally too!).

But we didn’t stop at attending and presenting at conferences. We decided to convene wetland professionals of all types from around the state and eventually around the region for a Delaware Wetlands Conference. Held for the first time in October 2001 at Cape Henlopen State Park, the agenda focused on wetland status in Delaware, wildlife and habitat management, monitoring, restoration and permitting.

Over the years the conference moved to the Dover Sheraton Hotel to the Dover Downs and now the Chase Center on the Riverfront in Wilmington. What started as a one-day gathering of 100 has expanded to a two-day event for 350.

With 8 conferences on the books we are still striving to make the conference worthwhile and effective. Although it requires a year of planning, hosting the Delaware Wetlands Conference is extremely rewarding. To see so many sectors of professionals gathered together with a common interest in wetlands and a desire to learn and collaborate is inspiring. We look forward to the 2020 conference already!

We’ve accomplished a lot for such a small program, but we still have a lot to do. Another early member of the program Chris Bason, Executive Director for the Delaware Center for the Inland Bays gives the program kudos for its accomplishments but questions if the resulting scientific information is being heeded.

Wetland science in Delaware is very strong thanks in large part to the WMAP and the EPA’s and State’s continued investment in the Program… The question on the minds of those that have worked so hard to understand the importance and condition of these extraordinary natural resources remains: will Delaware’s political leadership be moved by the 20 years of science indicating these wetlands need protection? – Chris Bason, Delaware Center for the Inland Bays

For now we will focus on gathering relevant information and sharing our work with familiar and new audiences alike. For example, we are focusing on providing realtors and homebuyers with important information and tools to navigate buying and owning wetlands.

In addition, in 2019 we will be releasing 10-year updated statewide wetland maps and examining how and where wetland acres have changed in a decade.

Every year we continue to set higher goals for our program to reach a wider audience, interact with more citizens, tackle new issues, and push our limits in the name of wetland science and wetland conservation. Remember, you can find us on this blog, our social media accounts above, or main website anytime of day for wetland fun facts, photos, wetland research and data. See you around!

Written on: May 8th, 2019 in Wetland Animals

By Erin Dorset, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Birding is always exciting in Delaware. While some bird species are year-round residents, many others are migrants traveling along the Atlantic Flyway. This keeps things interesting, as it allows birders to see a very wide variety of species throughout the year. A lot of these awesome birds exist in or near wetlands in Delaware, which makes wetland habitats great places to go birding!

Here are some of the best sites to see birds in wetlands in Delaware (though this is not an all-inclusive list). For each place, we describe location, wetland habitat types, and how to get around. This will hopefully help you find the best locations that suite your birding interests!

Location: Smyrna

Wetland habitat types: tidal marshes, impoundments, mudflats

Description: This large refuge is probably the most well-known birding spot in the state. While there are some short walking trails and some observation towers at Bombay Hook, most of the refuge can be explored along a 12-mile driving loop. There are many places to pull off of the driving loop to look for birds in the wetlands.

Additional info: Click here to learn more about birding at Bombay Hook and see the map of the refuge. Also, view the refuge bird checklist for more details about what time of year you are likely to see different species.

Location: Milton

Wetland habitat types: tidal marshes, impoundments, mudflats, forested wetlands

Description: Prime Hook is another large federal refuge that can be explored on walking trails, by driving, or by a canoe trail. It is the site of a large restoration project that was designed to rebuild degraded tidal wetlands, which means that birds should benefit from the project!

Additional info: Check out the refuge map. Also see the bird checklist for more details about what time of year you are likely to see different species.

Location: Dover

Wetland habitat types: tidal marshes, impoundments, mudflats

Description: This is a state wildlife area that is made up of several tracts of land.

There are several parking lots and boat ramps, most of which require you to have a Conservation Access Pass (CAP). While there aren’t any designated walking trails, you can stop along roadsides, or view birds from a boat or a wildlife viewing tower. Note that hunting is permitted here.

Additional info: Check out the map of the wildlife area.

Location: Lewes

Wetland habitat types: tidal marshes, impoundments, mudflats, forested wetlands

Description: This state park has many hiking and walking/biking trails throughout many habitat types. Some go through maritime forest and dunes, and others pass by tidal marshes and a large impoundment (Gordons Pond). There is also a nature center at Cape Henlopen, where you can watch a live osprey camera! Plus, volunteers can participate in a hawk watch every spring and fall here.

Additional info: Look at the map of the state park, and check out the park’s birding checklist.

Location: Townsend

Wetland habitat types: forested wetlands

Description: Blackbird State Forest is quite large; it is made up of 9 tracts of land with about 40 miles of trails. This means there are great opportunities to find birds in and around the forest’s freshwater wetlands! Be aware that hunting is permitted within the forest.

Additional info: See the maps of the state forest tracts

Location: Bear

Wetland habitat types: forested wetlands

Description: The Swamp Forest trail goes around Lums Pond and through patches of forested wetlands for over 6 miles, providing a great opportunity to see birds that are associated with wooded wetlands! There are also several other trails and a nature center to enjoy.

Additional info: View the map of the state park

Location: Frankford

Wetland habitat types: tidal marshes, mudflats, impoundments, forested wetlands

Description: This is a state wildlife area that is made up of several tracts of land.

It has several parking lots and boat ramps, most of which require you to have a Conservation Access Pass (CAP). While there aren’t any designated walking trails, you can stop along roadsides, or participate in the auto tour. You can also view birds from a boat or a wildlife viewing tower. Note that hunting is permitted here.

Additional info: See maps of the wildlife area tracts

To learn about some more great birding locations in Delaware, including places with non-wetland habitats, see the Delaware Birding Trail.

While these are not all-inclusive lists—and some birds may cross over from one habitat type to another– here are some of the bird species that you might encounter in different wetland habitats in Delaware.

Clapper rail; Virginia rail; Marsh wren; Seaside sparrow; Saltmarsh sparrow; Great blue heron; Snowy egret; Great egret; Willet; Least bittern; Northern harrier; Osprey; Common moorhen; Sora; Glossy ibis; Forster’s tern

Semipalmated sandpiper; Least sandpiper; Sanderling; Semipalmated plover; Greater yellowlegs; Lesser yellowlegs; Black-necked stilt; Ruddy turnstone; Dunlin; Short-billed dowitcher; Red knot; Willet

Mallard; Northern shoveler; Green-winged teal; Blue-winged teal; Northern pintail; Gadwall; Bufflehead; Canada goose; Tundra swan; Snow goose; American black duck; Ruddy duck; Black-crowned night heron; Yellow-crowned night heron; Green heron; Great blue heron; Common moorhen; Least bittern; Red-winged blackbird; American avocet

Wood duck; Cerulean warbler; Louisiana waterthrush; Warbling vireo; Yellow-throated vireo; Prothonotary warbler; Kentucky warbler; Yellow-throated warbler; Barred owl; Eastern screech owl; Great-horned owl; Wood thrush; Northern flicker; Downy woodpecker; Red-bellied woodpecker; American woodcock

Written on: March 11th, 2019 in Wetland Restoration

By Jules Bruck, University of Delaware

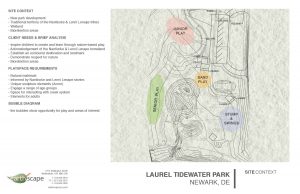

Great things come naturally in Laurel, Delaware including the new green infrastructure treatments that are popping up along the Broad Creek – home to the future Laurel Ramble. This past summer the Sussex County Conservation District broke ground on a parcel of land in the center of the Ramble plan called Tidewater Park. The project, designed to improve water quality in the area, was engineered by ForeSite Associates of New Castle, Delaware. Work began on two treatments – a vegetated bioswale and a constructed wetland, in early summer 2018.

The Bioswale

The bioswale was selected as a priority treatment due to the following factors:

The 300’ long gently meandering bioswale forms a diversion for runoff, permitting easier installation of the constructed wetland and fish habitat. It creates a viable, ecologically appropriate solution to aid in reducing pollutant loads to Broad Creek, which in turn makes a significant step forward toward meeting the demands of the town’s Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) permit.

The bioswale represents a permanent change in drainage patterns on site, and it is expected to be a long-lived treatment as long as the inlet is regularly inspected and maintained. It’s designed to meet the total maximum daily load (TMDL) requirements for 2.23 acres of existing impervious surface in the drainage area.

The Constructed Wetland and Tidal Fish Cell

The constructed wetland is approximately one acre is size, and planted with native grasses and sedges as well as some flowering herbaceous plants. It was designed to accept some stormwater surface flow from the upland areas as well as to allow the waters of the Broad Creek to enter during high tides.

According to the Stormwater Management Report prepared by FA in July 2016, “In keeping with the theme of the proposed playground as a nature-based feature and the Town’s goal to promote Laurel’s ecotourism industry, a tidal fish cell has been designed adjacent to the constructed wetland.”

“This tidal cell does not serve a regulatory function other than convey discharges from the constructed wetland to Broad Creek. Overflow from the constructed wetland is designed to discharge through a narrow v-shaped notch in the weir wall to help detain and slowly release runoff to the tidal fish area.”

Creating Native Wildlife Habitat with Native Plants

The new landscape has diverse plantings that will increase the native biodiversity on site and attract wildlife such as ducks and butterflies. We look forward to the spring so we can evaluate how the plants survived over the winter.

We anticipate the wetland will become important habitat for spawning fish, such as American Shad. In fact, we had to be careful about working in the water during the summer to avoid disruptions during critical times for the local native fish.

Good Planning = Easy Maintenance

After some minor touch ups and replanting of the plants that did not make it through the winter, the treatment should be relatively easy to maintain. University of Delaware landscape architecture students worked on a landscape management plan under the direction of Dr. Jules Bruck thanks to funding from UD Community Engagement Scholars and DE Sea Grant. We continue to work with the Town of Laurel to develop a management plan. We also want to keep an eye out for any invasive plants and provide training for the town’s landscape crews to help them identify and control non-native plants and noxious weeds. To that end, we’ve asked Tracy Wootten of Cooperative Extension to lend us a hand! We are working on some ideas to engage facilities and the community so the project remains a benefit to all. The Tidewater Park plan is a different type of landscape and you’ll start to see more of it as the Ramble plan is installed. It’s not just ornamental, it’s a working landscape.

This project was funded through two grants – the DNREC Community Water Quality Improvement Grant and the DNREC Chesapeake Bay Implementation Grant Program. Interested in learning more about this wetland and bioswale creation or the Laurel Ramble? Visit the Reimagining Laurel website. http://www.reimaginelaurel.net/