Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: September 19th, 2017 in Wetland Animals

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Did you know that Delaware has multiple species of crayfish? While crayfish may look like small lobsters, they are actually distant cousins. The most differentiating feature is that lobsters live in saltwater, and crayfish, crawfish, crawdads, or whatever you would like to call them, live in fresh to brackish waters.

Some crayfish species living in Delaware are naturally occurring here (native), while some come from other parts of the country (invasive), and they all come in various colors and sizes. You are likely to find these crustaceans in flowing streams, lakes, swamps, ponds, and seasonally wet wetland habitats. They live their lives safely burrowed in underground tunnels or hiding out in open water, or some combination of the two. Fun fact, as long as the crayfish’s gills stay moist, it can breathe on land or in the water.

Crayfish are opportunistic feeders using the two antenna on the top of their head to seek out the chemicals that “smell” most tasty to them. They will chow down on decomposing plant or animal parts, slow moving macroinvertebrates such as snails, underwater grasses, amphibians, and fish eggs. Interestingly enough though, juvenile crayfish seem to prefer a diet consisting of mostly meat, while adult crayfish seem content munching away on plant materials.

On the other hand, crayfish also serve as a tasty treat to bass, snapping turtles, raccoons, and herons, and are used as bait by fisherman to catch fish.

These hard-shelled critters also have interesting behaviors. To escape a predator, they will try to tail flip themselves away. Don’t think they are wimps though, because they aren’t afraid to get down and dirty. Fighting is commonplace among crayfish, whether it be over food, shelter, or selecting the perfect mate. They box, push, grasp, and grab at their opponent until one submits or loses a limb.

But, how does one crayfish know when the other has submitted? Crayfish have developed body language and chemical signals that let their opponent know when they’ve given up. If a crayfish lays its body flat against the ground with its claws forward, or if it does a tail flip and propels itself backwards, it has submitted and the battle is over.

Crayfish behaviors can vary by species, especially when it comes down to aggression. For example, the red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) is known for its very aggressive behavior and delicious taste, and it just so happens to be an invasive species right here in Delaware. It uses its aggressive behavior to out-compete native species of crayfish and amphibians for shelter and food.

Native to the U.S.’s Gulf Coast, the red swamp crayfish made its way to Delaware through people releasing or disposing them as unwanted food, pets, or bait. One paper from Indiana hypothesized that flushing crayfish down the toilet was an inappropriate way to dispose of them because they were being found around waste water treatment facilities, “having apparently survived treatment.”

Long story short, crayfish are cool, but the invasive species are bad, and never flush unwanted animals—including crayfish– down the toilet because you never know where they might end up (or what they might turn into).

Red Swamp Crayfish Identification:

• Tolerates a range of salinities and pollution

• Can grow up to 5 inches long

• Dark red in color

• Raised bright red spots on claws and body

• Juveniles are not red and can be difficult to identify

• Have an approximate two year life span in the wild

• If you see one, please report it to the Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife at 302-735-8655

Written on: September 19th, 2017 in Wetland Assessments

By Kari St.Laurent, DNREC’s Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve

Wetlands are more than just a beautiful photo opportunity. If you are a reader of this blog, you are probably aware that tidal wetlands can protect shorelines from storm surge, reduce nutrients, and provide habitat for critters like shellfish, crabs, and fish. These benefits are collectively known as ecosystem services. Recently, there is another ecosystem service that has been gaining interest from wetland scientists, coastal resources managers, and policy-makers alike – the ability for tidal wetlands to trap and store carbon!

Tidal wetlands can store mass amounts of carbon within its thick layers of sediment. Plants, including Spartina alterinflora, take in atmospheric carbon dioxide during photosynthesis and turn it into part of their cellular structure. When these marsh plants die, that carbon can be buried into the marsh sediment where it can stay trapped as organic matter for millennia. Organic matter can also be deposited onto a marsh by tides and water coming off from land. This process of carbon going from the atmosphere into marsh plants and sediments is called carbon sequestration.

One key feature of a tidal marsh is its ability to accrete, or be able to vertically build-up sediment to keep pace with local sea level changes. As this layer of marsh sediment gets deeper and deeper, it becomes harder for this trapped carbon to get released back into the atmosphere. Thus, marshes can be a sink for carbon dioxide!

This storage of carbon within tidal wetland ecosystems has earned the name blue carbon. Impressively, tidal wetlands can store more carbon per area than a forest because of its deep layers of mud – measured as deep as 32 feet in Belize. And that carbon in a tidal wetland can be stored for 1000’s of years while systems like a rainforest store carbon for shorter periods, such as decades to centuries. This makes blue carbon an important component of the global carbon cycle.

Healthy marshes will continue to trap and store carbon, in addition to providing valuable habitat, protection from storms, and natural filtration of nutrients. However, when marshes are lost or degraded, that carbon storage benefit is lost – and even more, that previously stored carbon can be released back into the environment. The protection and restoration of wetlands is a great way to help continue carbon sequestration and storage within tidal wetlands.

So just how much carbon is sequestered each year within Delaware’s approximately 73,000 acres of tidal wetlands? This past summer, DNREC-Delaware Coastal Programs hosted Bryce Stevenosky, a DENIN intern from the University of Delaware, to help us understand this question using published scientific literature. While this is just a back-of-the-envelope type of estimate, it starts to put the amount of blue carbon into perspective for Delaware’s wetland scientists.

Bryce estimated the amount of carbon sequestered each year into Delaware’s marsh sediments is 57,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide. To put this into perspective, the average car emits 4.7 metric tons of carbon each year. This means that Delaware’s wetlands sequester the emissions of over 12,000 cars each year. That’s greater than the population of Smyrna!

This estimate is just the beginning for Delaware’s coastal resources managers and scientists to understand the role wetlands play in storing carbon dioxide, and what we could stand to lose if wetlands are lost. More work needs to be done in Delaware to understand these complex processes and put a site-by-site specific value on just how much carbon Delaware’s tidal wetlands are trapping for us.

Written on: September 13th, 2017 in Wetland Restoration

By John G. Cargill, IV, DNREC Division of Watershed Stewardship/Division of Waste and Hazardous Substances

The National Vulcanized Fiber (NVF) plant located in Yorklyn, Delaware has a rich history with humble beginnings in grist, snuff, lumber, and cotton. By the mid 1800s, production in the valley shifted to paper, and by the early 1900s shifted again to vulcanized fibre. Due to the early success of fibre production, the local Marshall Brothers Company expanded into the National Fibre and Insulation Company and later into the NVF Company. Operations at NVF between 1960 and 2003 were busy. The main mills and the Marshall Brothers Mill were operated 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, moving approximately 40-41 million pounds of material annually. Eventually demand and production slowed, and by 2008 the staffing and traffic of the mills had reduced to about ¼ of the totals from the height of the company. By 2009, the NVF Company had declared bankruptcy and shut down the facility for good.

At the same time that NVF operations were winding down, the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control’s (DNREC) Division of Parks and Recreation (Parks) was acquiring land in and around the valley. By the end of 2008, Parks was managing 192 acres of valuable conservation and cultural resource lands known as Auburn Heights Preserve (which also includes the original Marshall family mansion and its steam car museum) and another 121 acres known as the Oversee Farm. Between the two areas of conservation land, and adjacent to the Red Clay Creek, was the former NVF Company plant. Here’s where things get interesting…

Concerns and interest in the NVF properties were far reaching. DNREC’s Division of Waste & Hazardous substances was concerned about hazardous materials and unknown environmental issues; DNREC’s Division of Water Resources was concerned about known impacts to aquatic life in the Red Clay Creek from plant operations; DNREC’s Division of Soil and Water Conservation was focused on historic flooding problems and the hazards posed by an abandoned facility in the flood plain; DNREC’s Division of Parks and Recreation saw an opportunity to connect its other properties in the valley; private investors were interested in the redevelopment potential of creek-side property; and the surrounding community was concerned about all of it. So now what ?

Working as a unit, DNREC put together a multi-divisional working group that began to secure the site and gather information about environmental conditions at the site. DNREC Parks worked with a private investment group to acquire the 119 acres of NVF Company land from the Bankruptcy Trustee, and soon after negotiated rights to various parcels for future Park related development and connection of existing Park amenities. Through this unique partnership, DNREC assumed responsibility for the assessment and environmental cleanup of the former plant properties, while the private developer took responsibility for all asbestos abatement and demolition of existing unwanted structures.

Fast forward to August 2017. All of the structures that will not be redeveloped have been demolished. The feasibility study conducted to determine the best cleanup options for contaminated portions of the property has been, more or less, implemented and completed. Aside from the continuously operating groundwater remediation system that keeps dissolved zinc in groundwater from entering the Red Clay Creek, the most aggressive and costly portion of site remediation entailed zinc source removal (from soil) and creation of a 2-acre wetland to serve as flood water storage capacity.

During the excavation project, over 170 tons (340,000 pounds) of zinc was removed from the soil beneath the former manufacturing facility. In addition, between 500 and 700 pounds of zinc are recovered monthly from the groundwater through the operation of the treatment system.

The majority of non-permeable surfaces have been removed from the site to foster better drainage, and more wetland projects are planned on DNREC owned properties in the valley for additional flood water storage capacity. Finally, pervious paving materials will be used in all roads and parking lots associated with future site redevelopment.

Hazardous Substance Cleanup Act (HSCA) funds have supported approximately $4.5M of the assessment and cleanup efforts, with another $3M on loan from the Clean Water Loan Fund for the zinc source removal/floor mitigation wetland project. Additional State funding is provided to DNREC Parks for ongoing development of trails and other area amenities. At this point in time, the former plant site is ready for additional development, both commercial and/or residential.

Moving forward, the Wilmington and Western Railroad steam train will continue to run through the valley as it always has, but a new turntable and a train station will be added to the former NVF Company property to improve public access to services and amenities. Miles of hiking trail will be accessible from this centralized location, including three historic bridges that will cross the Red Clay Creek within the valley.

An outdoor amphitheater is planned to serve the Delaware Symphony Orchestra as their summer concert home, and residential redevelopment is being planned for one of the former mill building sites (including a stream restoration project along Yorklyn Road).

Public water and sewer are currently being extended to the site to support these and other amenities, including restaurants and shops, that will inevitably follow as the realization of this unprecedented partnership between public and private entities for renewal and revitalization of the Auburn Heights/Yorklyn Valley area are realized.

Written on: May 24th, 2017 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Restoration

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

What is one way to give a marsh a lift with the challenge of rising seas? Spray the muddy material that has been dredged up from the bottom of a creek in a thin layer on top of the marsh. But how much mud is too much, and can the plants survive? These are a couple of the questions we (Wetland Monitoring & Assessment Program) set out to answer.

In 2013, Pepper Creek in Dagsboro was set to be dredged, so we rallied the troops and came up with a plan to test out how the beneficial reuse of dredge materials (also called thin layer application) affect marshes in Delaware. The resulting spoils from dredging were thinly sprayed over the marsh at the Piney Point Tract of the Assawoman Wildlife Area, and long term monitoring stations were set up.

For the past three years we have been looking at how the plant community has responded to the application, and how the marsh surface has changed by performing Real Time Kinematic (RTK) GPS transect surveys of the area and measuring surface accretion with feldspar marker horizon plots.

From the data we have been gathering we’ve figured out a couple of things that work and some things that need further study for future projects:

Establish a limit to the amount of mud that can be sprayed in the application area. For our area, we suggest approximately 10 to 12 centimeters. The plants in areas that were more thickly sprayed with mud still struggle to grow through the mud. To supplement these thickly applied areas, we planted 2600 smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) plugs to try and fill in the bare areas. We even started a mini-experiment to see if planting in clumps verses rows allows the little beauts to survive better. We’re still collecting data on the mini-experiment, but hope to have some interesting results soon.

Once the thin-layer of sediment has been applied to the marsh surface, it takes time for the muddy water to level out across the marsh and for the suspended sediments to fall out of the water. More information is needed on how mussels respond to being covered with mud. How thick is too thick for them?

So the nitty gritty of it is that spraying dredge materials on top of a marsh can increase the height of that marsh. But, careful attention must be paid to how thickly the mud is sprayed, and the site should be monitored for problem areas that need replanting.

This project was done in partnership with DNREC’s Shoreline and Waterway Management Section. For more information or questions about this project, please contact Alison Rogerson at alison.rogerson@delaware.gov or 302-739-9939.

Written on: May 24th, 2017 in Wetland Assessments

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

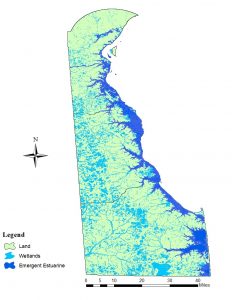

Coastal wetlands are a hallmark feature of the Delaware’s Bayshore, making up about 23% of all wetland types in the state. Because of the many beneficial services these wetlands provide, such as wave energy reduction, the survival of coastal wetlands is an important part of protecting our seaside communities from threats associated with the changing climate.

We here at DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program (WMAP) are doing our part to track changes in coastal marshes with the long-term monitoring of fixed sites in the Christina and Broadkill watersheds.

To do this, we’ve joined in on the Mid-Atlantic Coastal Wetland Assessment (MACWA) method by maintaining Site Specific Intensive Monitoring sites, also called SSIM (pronounced sim). This monitoring effort establishes fixed stations in coastal marshes and looks at a couple of different factors including water quality, soil quality, plant community, and marsh surface characteristics to help determine if that marsh is capable of keeping up with sea level rise.

There are currently seven fully established SSIM stations in the Delaware Bay Estuary network with two of them residing right here in the little state we call home, Delaware. Two or three times a year, three to four scientists (or scientists in training) slide on their hip boots, head out to the marshes and gather data.

The first SSIM site was installed in Delaware in 2010 on the Christina River in the Russell Peterson Urban Wildlife Refuge. This site is a freshwater site that is impacted by both the past and current chemical industry and from marsh fragmentation caused by the construction of highways in the 1960’s.

The second site in Delaware is located in the Great Marsh Preserve along Canary Creek, an offshoot of the Broadkill River, in Lewes and was installed in 2014. This station is the most downstream location out of the seven in the Delaware Bay Estuary and has the saltiest water of all of the sites because of its proximity to the Atlantic Ocean. The surrounding landscape of this area is agricultural, with some housing communities. Like most salt marshes along the east coast, these areas were historically ditched for mosquito population control.

With each passing year we gather more and more data at these two SSIM sites that will help us understand more about our marshes’ ability to keep up with sea level rise. Be on the lookout for future updates about this project!

This project is done in partnership with the Partnership for the Delaware Estuary (PDE).

Written on: March 16th, 2017 in Wetland Restoration

By Andrew Martin, Delaware Wild Lands field Ecologist

The Great Cypress Swamp once covered nearly 60,000 acres. Although a long history of ditching and draining for agriculture and development has reduced its vast expanse, the Swamp remains Delmarva Peninsula’s largest contiguous forest and largest freshwater wetland.

For the last 50 years, Delaware Wild Lands (DWL) has been strategically purchasing and restoring this delicate ecosystem. The first parcel that DWL ever acquired was Trussom Pond in 1961. This purchase launched our efforts to protect Delaware’s iconic cypress swamp habitat. Today, DWL owns and manages more than 10,5000 contiguous acres of the Great Cypress Swamp in Sussex County and overlapping the state line into Maryland.

Trussum Pond and the 1,200 acres of unique wetlands associated with it, were handed over to the Delaware State Parks system in 1991, but our commitment to the private protection of wetlands continues. Today, as Delaware’s largest non-profit non-governmental landholder, DWL owns more than 21,000 acres throughout Delaware, and we’re actively engaged in wetland restoration in all three counties.

The Great Cypress Swamp is home to our largest and most ambitious wetland restoration work. It also contains the headwaters of the Pocomoke River, an important tributary to the Chesapeake Bay. In 2011, we installed a series of water control structures in the historic ditches, allowing us to hold back millions of gallons of water that otherwise would have drained away. In only six years, we have rehydrated hundreds, if not thousands of acres of the Swamp.

Our wetland restoration in the Great Cypress Swamp began, perhaps surprisingly, with a 150-acre timber harvest. At the time, this area was a dry woodland. Harvesting timber helped us prepare the site as we began redirecting water and creating a restored emergent wetland. The revenues from timber sales are reinvested back into restoration expenses.

Since 2011 we’ve planted 173,000 native trees – a few thousand Baldcypress seedlings throughout, and tens of thousands of Atlantic White-cedar planted in the transitional and upland areas. Later this spring, we’re planning to plant 21,000 more trees.

As ecological systems are restored in the Swamp, a rich diversity of animal species is also returning. Each spring, hundreds of acres of newly-flooded woodlands echo with the “clack-clack-clack” of Carpenter Frogs and the mating calls of other species of frog. In some places, mature trees are dying in standing water, providing habitat for Red-headed Woodpeckers, Wood Ducks, owls, and other cavity nesters.

Spotted Turtles – named by the Endangered Species Coalition as one of the top ten species most threatened by habitat fragmentation – now have hundreds of new acres to spread out and spawn. A new abundance of seed from wetland grasses, aquatic insects, amphibians, and even fish now provide food for wading birds like herons and egrets, and waterfowl like Mallards and Black Ducks. It is not uncommon to see dozens of Bald Eagles and other raptors soaring overhead.

Because of its delicate and sensitive nature, the Great Cypress Swamp – like all Delaware Wild Lands properties – is not open to unscheduled visitation. We do, however, offer guided tours. And the next opportunity for the public to visit the Swamp is even more fun than usual! Come join us on Saturday, May 20 for some great music at our annual Baldcypress Bluegrass Festival.

We’ll have five foot stompin’ bands playing all day from 12-6PM on a stage that backs right up to 150-year-old Baldcypress trees. Craft beers and wines will be flowing and several food trucks will be serving a delicious menu. New this year is a craft vendor area with members of the Dewey Artist Collaboration and DNREC’s Mobile Science Lab with interactive exhibits about the Chesapeake Bay Watershed.

Tickets to the festival include free bus tours through the Great Cypress Swamp that will pass right by our massive wetland restoration sites. Tickets are only $25 in advance or $35 at the gate. All proceeds benefit Delaware Wild Lands. Visit www.dewildlands.org or http://facebook.com/DelawareWildLands/events for more information and tickets.

Written on: March 15th, 2017 in Wetland Animals

By Amy Nazdrowicz, Landmark Science & Engineering

As residents of the Delmarva Peninsula, we are blessed with a high diversity of herpetofauna, (reptiles and amphibians), in part because of our landscape position which transitions between two physiographic regions: the coastal plain in its southern and central portions to the piedmont in the north. And no place showcases our herpetological diversity as our wetlands in springtime! Whether you reside in the piedmont or coastal plain, the wetlands of the Delmarva Peninsula are a special place in the spring when the water tables tend to be at their highest and our herp species are becoming more active.

The raucous calls of our early breeding frogs, the Spring Peeper, Wood Frog, and New Jersey Chorus Frog, are a promise of the quickly approaching spring and the much appreciated sunshine that comes along with it. But it’s a quieter harbinger that is an especially welcome sign of spring and lover of sunshine. The rare and beautiful Bog Turtle emerges along with the vegetation from a winter spent hibernating down in the muck or in subterranean tunnels surrounded by slowly flowing groundwater that provides protection from freezing. It is within a handful of our northern spring-fed wet meadows that the warm spring sunshine entices the Bog Turtle up to the surface to bask and prepare for breeding. I was once lucky enough to watch a male Bog Turtle emerge from a tunnel entrance among the roots of an Alder and blink into the sun, completely caked in mud accumulated during his winter hibernation. That was in early April but I have found Bog Turtles near the surface as early as March 20.

The Bog Turtles’ need for plenty of sunshine continues beyond the springtime into their breeding season where mating occurs on the wetland surface from approximately mid-April through mid-June. The summer sun remains important to gravid females during gestation and they lay their eggs in peak summer atop plant tussocks to fully absorb the sunshine. Averaging only 3-4 inches in length, an adult Bog Turtle can fit into the palm of your hand. The hatchlings, breaking out of their eggs in late summer or early fall, are no larger than the size of a quarter.

Small, dark, and masters of camouflage, the only conspicuous identifying characteristic of a Bog Turtle is a sunny splash of yellow-orange coloration on each side of the head. As plenty of sunshine is an important habitat component, crucial Bog Turtle habitat includes open, emergent wetlands with little to no tree canopy. And, as the Bog Turtle and their habitat are federally protected under the Endangered Species Act, Bog Turtle wetlands must sometimes be actively managed to keep ecological succession at bay and to maximize the sunlight reaching the wetland surface.

As plenty of sunshine is an important habitat component, crucial Bog Turtle habitat includes open, emergent wetlands with little to no tree canopy. And, as the Bog Turtle and their habitat are federally protected under the Endangered Species Act, Bog Turtle wetlands must sometimes be actively managed to keep ecological succession at bay and to maximize the sunlight reaching the wetland surface. After a long winter, it is safe to say that humans and Bog Turtles alike are looking forward to the return of the springtime sunshine! Happy Spring and have fun exploring the wetlands of Delmarva!

Amy (Alsfeld) Nazdrowicz is an Environmental Scientist with Landmark Science & Engineering, a civil engineering firm providing civil/site design, surveying, GIS, and environmental consulting services. As a Recognized Qualified Bog Turtle Surveyor certified in Delaware, Maryland, and Pennsylvania, Amy and her Bog Turtle team conduct Phase I, II, and III Bog Turtle Investigations, as well as radio telemetry and other Bog Turtle monitoring services, throughout the region. Amy works from Landmark’s corporate headquarters in New Castle, DE and can be reached by phone at 302-323-9377 ext. 145, or by e-mail at amyn@landmark-se.com. Visit Landmark’s website for more information and services.