Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: December 9th, 2016 in Wetland Animals

By Kari St.Laurent, DNREC’s Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve

Fiddler crabs are one of the most iconic critters in the salt marsh. Male fiddler crabs have an unmistakable single large claw, paired with a tiny claw, which is used to court female fiddler crabs. But did you know that crabs start their life as microscopic zooplankton? Fiddler crabs undergo multiple molts to grow from a tiny, drifting zooplankton to the rock-sized crabs we see scurrying around the marsh each summer.

Fiddler crabs create complex burrows within the marsh that serve as their homes, which can make the brown marsh mud look like Swiss cheese. Research has suggested that fiddler crab burrows help to move oxygen from the atmosphere to the roots of marsh cordgrasses like Spartina alterniflora. However, too many fiddler crab burrows can stop cordgrass root mats from forming and potentially hinder plant growth. Thus, a change in fiddler crab populations can affect salt marshes in different ways, making it a fine balance with a lot of unknowns.

In the upcoming months, researchers, students, and volunteers working at the Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve will be monitoring zooplankton diversity at the St. Jones Reserve in Dover. One of the most common types of zooplankton found in the brackish sections of the St.Jones River are zoea, or larval crabs! This monitoring effort will help us better understand which species of zooplankton are present and how that diversity changes on both short and long timescales.

Additionally, in the upcoming summer, researchers from the National Estuarine Research Reserve System are hoping to conduct a study to look at crab burrow densities within different marshes across the country. Connecting the fiddler crab burrows we see in the ground with the microscopic baby crabs swimming in the water, will help us understand if fiddler crab populations are changing, and if that change has an effect on our salt marshes, for better or for worse.

Stay tuned for volunteer opportunities and educational programs!

Written on: December 9th, 2016 in Education and Outreach

By Mary Rivera and Debra Forest, DNREC’s Division of Fish and Wildlife Aquatic Resources Education Center

The quiet of a peaceful morning in the Woodland Beach saltmarsh is interrupted by a flock of 60 lively fifth grade students. Squeals of delight emanate from several of the children at the fish station where they get a close-up look at native fish. Many of the students have never touched or held a fish before. Their nervous giggles are replaced by wide grins when they hold a mummichog or bluegill and learn about fish characteristics and adaptations.

At the macroinvertebrate station, several budding fifth grade scientists dip net in a freshwater pond, collecting specimens to identify and study. On the boardwalk, a group of students conduct water quality tests on a bucket of brackish water. The kids take turns measuring DO, salinity and pH, using an array of testing equipment. Another group moves along the boardwalk on a scavenger hunt for typical plants that grow in this unique ecosystem. Ten more students sit on benches in one corner of the boardwalk, listening intently to the natural sounds of the marsh.

The Eco-Explorers Program is designed to complement the science curriculum for fifth grade classes in Delaware. Participating teachers receive training and materials they will use in the classroom to introduce their students to the topic of wetlands. After completing the classroom segment of the program, teachers bring their classes to the Aquatic Resources Education Center near Smyrna to spend a day outdoors being “scientists”.

Parent volunteers accompany the school groups to chaperone the students and help them as they explore the saltmarsh. Often the parents are as thrilled and engaged as their children as they discover this wonderful and valuable locale.

Students have the opportunity to investigate six different eco-stations in the marsh where they learn about fish, macroinvertebrates, plants, and water quality. They also learn to observe and interpret signs of animals that live in the salt marsh. They explore the ARE’s boardwalk and ponds to discover the relationship of the marsh to Delaware Bay. The guided field work reinforces classroom learning and allows the students to observe first-hand the living and non-living components of the saltmarsh ecosystem.

Eco-Explorers activities are hands on and students are encouraged to try tasks that real scientists would perform when studying an ecosystem. Activities are led by a talented and knowledgeable staff of seasonal employees and volunteers. Field trips are offered every spring and fall and available dates fill up quickly with teachers eager to explore the marsh with their students.

Over the years, tens of thousands of students, parent chaperones and teachers have had the opportunity to participate in the Eco-Explorers Program and take away a deepening respect for the value and importance of Delaware’s wetlands.

The boardwalk at the Aquatic Resources Education Center is open to the public whenever there are no scheduled programs. Visitors to the Center will find this hidden gem situated along Route 9 near Smyrna. They can stroll along the boardwalk, enjoying beautiful marsh vistas and glimpses of the abundant birds and wildlife that inhabit the marsh. Two stocked, catch and release fishing ponds are also available for public use.

A new Aquatic Resources Education Center is scheduled to open very soon in partnership with Delaware’s Bayshore initiative. The new facility will provide additional indoor and outdoor interpretive areas plus new hiking trails.

For more information about the Eco-Explorers Program and the Aquatic Resources Education Center, go to de.gov/arec.

Written on: December 9th, 2016 in Wetland Assessments

By Katie Georger, Delaware Center for the Inland Bays

In November, the Delaware Center for the Inland Bays (CIB) released the 2016 State of the Bays report, a 70-page compilation of environmental data about the Rehoboth, Indian River and Little Assawoman Bays and their watershed. In assembling this report, we considered thirty-five environmental indicators to determine the health of our watershed. As you may have guessed, one of these indicators is salt marsh acreage and condition.

So what did we find? Our salt marshes are slowly disappearing – and with more than one culprit responsible.

Urbanization and Development

Perhaps the most well-known cause of wetland loss is urbanization and development. Between 1938 and 1968, about 22% of the Inland Bays’ salt marshes were lost to excavation and filling for development. Luckily, this trend has slowed due to Delaware’s 1973 Wetlands Act which legally protected salt marshes.

Still, in the last five years, developed areas in the watershed increased by 7.8 square miles (11%), replacing agricultural lands, upland forests, and wetlands. And with the population of the watershed projected to increase in the coming decades, the demand for land is sure to continue. Currently, most direct destruction of salt marsh in the Inland Bays watershed has been halted. That means that the recent cause of marsh loss is a different beast altogether.

The Drowning Marshes

Since 1992, there has been a noticeable increase in the amount of open water in the interior of our salt marshes. While such open water pools are not completely uncommon, the amount of water trapped in them is excessive. Our marshes are slowly drowning. There are actually thought to be two causes for this phenomenon: sea level rise and old ditches.

As you would expect, sea level rise is slowly causing the marshes to be underwater more frequently and for longer periods of time, as higher tides flow in and out of the Indian River Inlet. The old mosquito control ditches are contributing to this drowning. These ditches were intended to control mosquito populations by allowing water and fish into an otherwise marshy area, where they can feed on mosquito larvae. Now too much water is getting into in the interior marsh, where it becomes trapped. Between these ditches letting too much water into the marsh, and sea level rise creeping up higher, these important habitats are slowly becoming lost in the waters by which they once thrived.

Wetland Loss Affects Us All

The total acreage of salt marshes fringing the Bays was 7,300 when last inventoried in 2007- a net loss of over 3,500 acres since 1938. This means that we are losing protection from flooding and erosion, our natural filter for pollutants, and important carbon storage. But the loss of marshes is also harmful to water quality, as well as living resources in the Bays. Degradation of salt marshes means loss of critical habitat for native critters including diamondback terrapins, blue crabs, mussels, oystercatchers, laughing gulls, terns, egrets, blue herons and more.

Looking Ahead

Activities to protect natural habitats in the Inland Bays watershed have nearly stalled since the previous State of the Bays report was published in 2011. Our wetlands are disappearing. As we look to the future, it is obvious that funding and incentives for conservation, enhancement of forested buffers, and wetlands protection are gravely needed. What can we do?

Written on: September 7th, 2016 in Wetland Assessments

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Did you know that 50% of wetlands in our coastal plains ecoregion are in good condition? The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) organized the National Wetland Condition Assessment (NWCA) in 2011 to get these data, and now our Program (Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program) is again helping to assess more of Delaware’s wetlands to contribute to the 2016 NWCA.

2011 National Wetland Condition Assessment In Brief:

Five years ago, the EPA conducted a wetland assessment to look at the changing conditions and health of the nation’s wetlands. This study broke the continent into four separate ecoregions, with Delaware falling into the coastal plains ecoregion. The ecoregion includes the Mississippi Delta and extends up to Cape Cod, Massachusetts.

For all wetland types in the coastal plains region, 50% of the estimated wetland area is in good condition; 21% is in fair condition and 29% is in poor condition based on the vegetation index used.

During the 2011 NWCA field season a total of 513 randomly selected sites were sampled from across the U.S., 17 from Delaware, representing 30,893,305 acres nationally. Wetlands were surveyed by using an army of field crews stationed across the nation. We were lucky enough to be one of them.

All in all, 48% of U.S. wetlands were found to be in good condition; 32% is in poor condition and the remaining 20% is in fair condition.

2016 Field Work

This summer we are at it again, collecting wetland data for the EPA about wetland health from 12 sites across Delaware. Some of the sites were repeats from 2011, and some of them were new. Each site visit involved 4 people from our program, and a soil scientist from National Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) geared up to go out and look at soil composition, plant communities, water quality, and buffer stressors. For a more detailed description of each parameter we looked at, please visit the 2011 Technical Report. Look for a report on the 2016 data from the EPA in the future!

Written on: September 7th, 2016 in Wetland Restoration

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

A hot topic for scientists and residents of Milton as of late, has been the Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge Marsh Restoration project. This Refuge had multiple breaches in its freshwater impoundments where saltwater from the Delaware Bay cut its way through the dunes. The breaches caused significant flooding; massive vegetation die offs, and returned the habitat from its man-made freshwater system to its historic slightly salty brackish system.

To solve these problems, the Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge took on one of the largest restoration projects in the U.S. in the fall of 2015. The end goal, to create a self-sustaining system and return all the impoundments to a brackish tidally influenced ecosystem. The Refuge closed breaches, created over 20 miles of channels, planted thousands of plants, scattered thousands of seeds by airplane throughout the landscape, and provided design input for DelDOT’s new bridge.

So how will they know if it worked?

That’s where we (the Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program) come in and help. In the summer of 2015, we provided baseline wetland monitoring before any restoration work had begun. Then, after the Refuge finished this summer we came back to do the first post restoration sampling.

Preliminarily, we have seen some remarkable changes in the landscape.

Two of our assessment points now have a channel flowing through them. This makes it harder to walk around our sites, but should provide some interesting data in the future on channel impacts to a developing wetland. One of the most visually noticeable changes is the lack of water in some of the assessment sites. Sites that were once completely covered with water pre-restoration now appear high and dry post-restoration even though they do not have any significant elevation change.

But, the most promising response to the restoration is the colonization in these open areas with various plant species; Bulrush, Common Rush, Sweetscent, and Marsh Hemp to name a few. Leptochloa fascicularis, Bearded Sprangletop, is a salt tolerant annual that has become more prevent and responded to the new and changing conditions. As expected, the plant communities are changing, and will continue to change and adjust over the next few years.

We are just starting to dig into our data, and will continue to monitor the Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge Marsh restoration for the next three years in the hopes to better understand how wetland restorations change the landscape and return the vital wetland functions that we count on everyday.

What We Looked At, Quick and Dirty:

Written on: August 19th, 2016 in Wetland Assessments

Old abandoned car along Christina River.

People have been creators of some amazing inventions throughout history: wheels, cars, electricity, plastics and more! But what happens to these creations when they have outlived their use or are no longer wanted? You’re probably guessing that they end up in places like the dump, or antique stores or junk yards. But, would you believe that these unwanted items also end up left, dumped, or washed into our wetlands and their buffers?

Wetlands have the natural ability to clean and purify our waters by trapping excess sediments and nutrients, and they also have the unfortunate ability to trap our trash. That trash then prevents the wetland from being able to function fully, which isn’t good for us and the health of our waters.

WMAP staff with lamp post globe.

We here at the Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program, run into quite a few unique items as we walk through and assess Delaware’s wetlands. So, we thought we would put together a short list to show the array of man-made items we have found across Delaware, and let you ponder whether you think these items are “trash” or “treasures”.

From cool to creepy to junk, here are some of the items we have run across: golf balls, baby doll heads, Barbie’s, trash cans, BB gun, barrels, buoys, lamp post shades, glass bottles, crab pots, paddle boats, tires, cars, cranes and signs. Click here for more photos.

Moral of this story; if you see trash in or near a wetland, help a wetland out, and pick it up to properly dispose of it at the dump or antique store (Who knows, you might even make a little money.). As the saying goes, one man’s trash is another man’s treasure.

For more information on illegal trash dumping in Delaware or to report illegal dumping, please visit Delaware TrashStoppers.

Written on: August 4th, 2016 in Wetland Assessments

By Tess Strayer, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program Summer 2016 Summer Seasonal

Growing up, I spent the majority of my childhood outdoors with friends, family, and the occasional wild animal. Whether it was hiking, biking, fishing or playing we were constantly exploring, thus you would think my outdoor experience would help better prepare me for field work this summer. When I accepted an internship position with Delaware Wetlands, I knew working outside in “adverse conditions” would be a regular routine. I gave no extra thought to those two words; I thought I could handle whatever was thrown at me. Well friends, I was wrong.

I learned very quickly what the true meaning of “working in adverse conditions” was and how to adapt this new type of field work. Do not underestimate the words “adverse conditions.” When I heard those words my immediate thoughts went to a few hot days, walking around in plastic boots in some vegetation. The reality couldn’t have been anymore different.

Picture this, a heat index of 95 with a real feel around 103+ degrees, a site where stepping off a vegetation platform meant falling to the other side of the earth and knowing this, you still fall every time. You will be the dirtiest you have ever been in your life before you even reach the first site. You will trudge through vegetation that was nicknamed “scissor leaves” and will slice you if you rub against them, and finally, a tan that would make the toughest farmer jealous. And while you think I am telling you these things to scare you away from field work, I wouldn’t change a single thing this summer.

Summer 2016 really challenged me both physically and mentally, but now looking back on these past three months, I have had some of the most fun I have ever had in a summer. This field work has prepared me for any possible “adverse conditions” and I now know how to survive if I find myself stranded in a marsh.

Remember kids, drink water and never step off the hummock.

Written on: May 30th, 2016 in Wetland Animals

By Maggie Pletta, DNREC’s Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve

The Delaware Bay is home to the largest population of horseshoe crabs in the world, which is just one of the many reasons the Delaware Bay is so special. The horseshoe crab has been around since before the dinosaurs and is an important animal to the ecosystem and to humans. Their blood is used in the production of LAL (Limulus Amebocyte Lysate) for testing the sterility of medical equipment; their eggs are the food that ensures migratory shorebirds can reach their destinations; and the crabs themselves are part of a thriving commercial fishery. However, since there are so many uses and needs of this extraordinary animal it is important that their numbers are tracked and managed.

To do this every year hundreds of volunteers assist organizations like the Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve (DNERR) to complete surveys of spawning crabs on Delaware Bay beaches every May and June during the full and new moons. During those moon phases the bay experiences the highest high tides, which is when the horseshoe crab comes up from its watery habitat to leave small green eggs in the wet sand. The volunteers head out on these nights, no matter how late, and walk a one kilometer distance on the beach stopping every 20 meters to count crabs. To ensure the volunteers are counting crabs in a standard size area, one meter by one meter square, they use a quadrat that they lay down on top of the crab line. Once the quadrat is down the volunteers count the number of male and female crabs, and then they pick up the quadrat and head down the beach to their next site. In all, one hundred samples are taken every night on every beach surveyed.

Once the data is collected for the season it is sent to Limulus Laboratories in New Jersey where the data is analyzed and compiled into an annual population report. This report is important because it is what resource managers use to set the harvesting regulations on the horseshoe crab in the Delaware Bay. And the volunteers are the key to a successful survey because without them we would never have enough people to complete the survey and collect this valuable data.

Written on: March 14th, 2016 in Wetland Animals

BY Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Thanks to all that extra water lying around, all sorts of amphibians start to come alive this time of year in Delaware. Frogs and salamanders use these seasonal pools of water, or wetlands, to breed and can only do so because predatory fish cannot survive the lack of permanent water. They then use the surrounding drier wetlands and uplands as summer habitat.

In your travels you may have started to hear the sounds of the Spring Peeper. Their sound is a high pitched “peep peep peep” and when singing together it has been said, they sound like a chorus of bells. The Spring Peeper males use these sounds to attract a mate, and are one of the earliest breeding frogs you will find in the State. They are brown to grey in color and can be identified by an X-marking on the back.

Spotted, Marbled and Eastern Tiger Salamanders are just a few of the salamanders that roam the state. These salamanders are in the mole salamander family because they spend most of their adult life under leaves, logs or in holes or burrows in the ground. They only return to the water, such as that in vernal pools, to breed during the winter/spring months.

Written on: March 14th, 2016 in Wetland Assessments

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

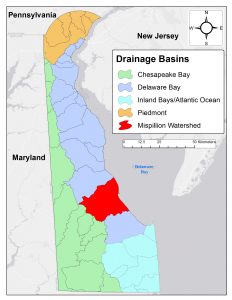

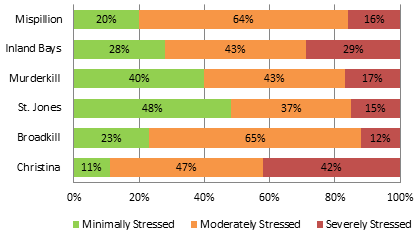

In the summer of 2012, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring & Assessment Program rated the health of wetlands in the Mispillion and Cedar Creek River Watershed’s tidal and non-tidal flat and riverine wetlands. The goal of this project was to summarize recent gains and losses in wetland acreage, assess the condition, and identify impacts on the wetland. The watershed received an overall grade of C; broken down into tidal wetlands receiving a B-, non-tidal flat wetlands receiving a C+, and non-tidal riverine wetlands receiving a C-. This was the sixth watershed in Delaware to be assessed.

The Mispillion Watershed lost 20% of wetlands since the early 1700s, with the majority due to conversion of land to agricultural fields or developments and erosion from rising sea levels.

The three most common impacts to wetlands were the:

Presence of invasive plants (such as Phragmites) that can out grow native plant species

Ditching of wetlands to remove its ability to hold water

Agriculture or development just outside the wetland blocking its ability to migrate landward.

The full report, data and report card are now available online.