Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: May 19th, 2023 in Natural Resources, Wetland Research

By Kayla Clauson, DNREC’s Watershed Assessment and Management Section

When you think of submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV), Delaware may not be the first state that pops into mind (we can’t be the first state all the time!) When SAV comes to mind, you may first think about the world-famous seagrass, Eelgrass (Zostera marina). In a marine environment, Eelgrass certainly runs the show being the only true seagrass in our region. However, there are a variety of other important species that exist in our less-salty waters. SAV can be found across different salinities, from saltier coastal oceans and bays, mixed estuarine rivers, and freshwater streams. In fact, as salinity of the water decreases, SAV species diversity increases!

So, what makes SAV unique? Submerged aquatic vegetation is any rooted, aquatic plant that grows entirely underwater. Like terrestrial plants, aquatic plants even flower and produce seeds for pollination underwater. These aquatic plants are important because they improve water quality by filtering pollutants and even trapping sediments that improve water clarity. These underwater plants face different challenges compared to their terrestrial relatives. One of the main stressors in Delaware is turbid or murky waters, which limits the sunlight in the water column that is needed by plant’s to grow

Although SAV is known to be important habitat, there have been minimal efforts to quantify what plants we have and where they exist in the First State. That’s why last year DNREC scientists began an official monitoring of SAV in freshwater streams across the state. Biologists visited 12 locations, looking at 9 different waterbodies and surveyed 6 miles of streams. These surveys documented 12 different species, with the most at the Brandywine Creek State Park. SAV beds ranged in size from dinner plates all the way up to a school bus! Among the beds were also various animals that benefit from SAV presence, including snails, freshwater mussels, and crawfish.

These survey results will be saved and added to more data collected this upcoming summer as DNREC works to catalog where and what SAV exists in Delaware. This information will help DNREC track SAV and work to increase populations of this beneficial plant community in the future.

SAV Spotlights: Check out some of Delaware’s SAV findings!

Written on: May 19th, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Natural Resources, Wetland Research

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Celebrate good times, come on! Yes, it’s the holiday we’ve all been waiting for – American Wetlands Month. This May marks the 32nd anniversary of recognizing the vital importance and need of wetland habitats across the United States. Now our program is out here everyday living and loving wetlands, but of course we greatly appreciate a designated celebration for the ecological, economic, and social health benefits that wetlands provide. To take it a step further this month, we wanted to educate folks (and even ourselves) about the challenges wetlands are facing as a natural resource across the world. Let’s take a stroll through some global wetland newsmakers.

Australia

Serious debate surrounds the Murray River, Australia’s second-longest river, as its floodplains may become one of the first attempts to engineer wetlands for water offsets in the world. Victoria, Australia has immense amounts of forested area, some of which are inhabited by First Nations people, that rely on regular flooding for survival. The Murray-Darling basin along the river has around 30,000 wetland pockets that are drying out due to climate change and the demand for irrigation by farmers. To address the problem and keep the wetlands alive with less water, the Victorian government has turned to floodplain infrastructure with nine major wetland engineering projects which have a $214 million USD price tag. Essentially the projects would artificially enable flooding in wetlands and surrounding areas, including ones of ecological and cultural significance, and provide water for farmers. The projects will go through an environmental assessment process this year, and the government is pushing its engineering initiatives through the Victorian Murray Floodplains Restoration Project. Citizens, scientists, and policymakers of Victoria have vocalized major concerns about the engineering projects, siding against the governments problem-solving effort.

Colombia

With almost 35% of Colombia’s land area covered by the Amazon rainforest, many citizens of the country are seeing the impacts of deforestation and exploitation of natural resources. In southern Colombia, throughout the wetland area of Lake Tarapoto, women of Indigenous communities are combating these changes through scientific research and education. Lake Tarapoto’s wetlands not only provide habitat for critical plants and animals, but support livelihoods for 22 Indigenous communities that heavily rely on aquatic resources such as fish and boat transportation. These women have stepped up to the plate to monitor, manage, and educate locals on the importance of wetland restoration, as well as increase awareness on the impacts from overfishing. The incredible work they have done over the years has caught the eye of environmental organizations like Amazonía Verde and Conservation International. Ichthyology (the study of fish), restoration, species research, community agreements – these women are doing it all for the wetlands and waterways.

Nigeria

In the Sahara of northern Nigeria lies the remnants of the Hadejia-Nguru wetland which once supported the livelihood of two million people and critically important habitats for migrating water birds. Big changes occurred in the 1990’s when the Nigerian government constructed two dams that together captured 80% of the water that flowed into the wetland areas. What has happened in the last 30 years is an oasis gone missing; most all the wetlands have dried out and majority of the population has left the area. The very little remaining wetlands are currently major centers of community conflict between farmers and herders as the desert invades their space to survive in poverty. As the uncertainty remains for the humans and biodiversity alike in this area, the one thing that is for certain is that issues need to be addressed for the first Ramsar site designated in Nigeria.

China

Now this is a different take on a wetland species we in Delaware hold near and dear to our hearts. China is experiencing an invasion of Smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) and has even launched a nation wide effort to control the species by 2025. Though the plant has been around in China since 1979, in the past few years it has taken on a life of its own spreading across tidal mudflats and increasing concerns for the government about the impacts on shipping channels and aquatic farms. Even more at risk are the birds migrating along the East Asian–Australasian Flyway, one of the most critical flyways in the world for coastal water birds. This invasive to the country has spread to many provinces where local control is simple not enough, and officials are suggesting management plans be pushed up through the National Forestry and Grassland Administration.

Indonesia

This video speaks for itself, but it is too impactful not to share. The country of Indonesia is made up of over 17,000 islands including small coastal countries such as Java, Sulawesi, and Sumatra, while also being the fourth most populated country in the world. What is even more astonishing is that this country is losing hundreds and thousands of hectares of land (1,000 hectares = 2,400 acres) in the last two decades due to erosion and sea level rise, with majority of impacts effecting large areas of mangrove wetlands. According to the Center for International Forestry Research, Indonesia is home to 3 million hectares (7,400,000 acres) of mangroves equating to 23% of the worlds mangrove area. With wetland restoration and habitat management a focus but a slow-moving train, the communities and wetlands throughout these island nations are at serious threat,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Q0eM7Tp7HE

Current projects, critical issues, policy updates, success stories – going worldwide with wetlands can certainly enlighten the most novice of nature fans. As we go through the next half of American Wetlands Month, our program challenges you to keep up the reading; see what you can learn or share about wetlands near and far. Like the old adage says, knowledge is power.

Written on: March 24th, 2023 in Natural Resources, Wetland Research

By Kenny Smith and Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

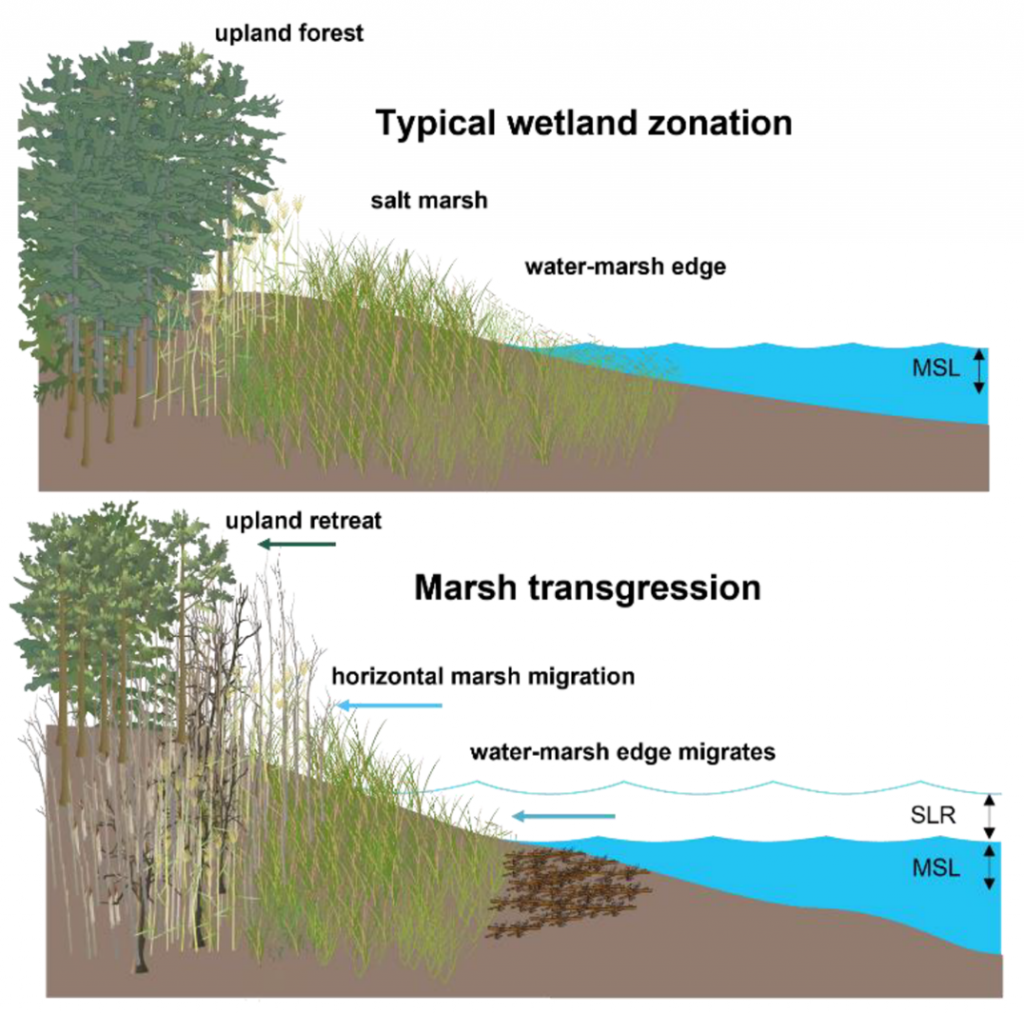

The most widely recognized migrations in the world involve animals: the red knot, monarch butterflies, salmon, wildebeest. But there is another migration happening everyday along the U.S. coastlines: marsh migration. This migration is not driven by the seasons, or daylight but is instead a response to sea level rise. Marsh migration is the act of tidal wetlands creeping slowly over time, moving away from rising sea levels towards higher, drier land to avoid drowning. Ground where the wetlands migrated from is eventually flooded and converted to open water forever.

While marsh migration is not as exciting as a stampeding herd of wildebeest in Africa or the Arctic Tern and its 40,000-mile trip spanning the length of Earth, it is a very important process happening throughout the country. Marsh migration is a natural way for wetlands to ensure their own survival into the future. Their persistence means continued benefits such as carbon storage, erosion control and storm protection. This process is not new but has become more essential as rates of sea level rise have increased in recent decades, especially in the Mid-Atlantic region. Between 2007 and 2017, Delaware lost 238.5 acres of vegetated tidal marsh, with over 66% of these losses attributed to erosion and sea level rise so it is an important topic.

As wetlands migrate, they convert the upland habitat that they move into. But not all upland areas are suitable to become tidal wetlands. How do we know where they will go in the future? How can we make sure they have room to migrate into? If coastal wetlands are so important, we should be planning ahead to ensure wetlands have a future along our coasts. Suitable migration habitat is usually shoreline that is natural and free of hardened structures that act like a barrier, have gentle slopes that allow wetlands to inch up gradually, and poorly drained soils that create wet, saturated conditions that wetlands need.

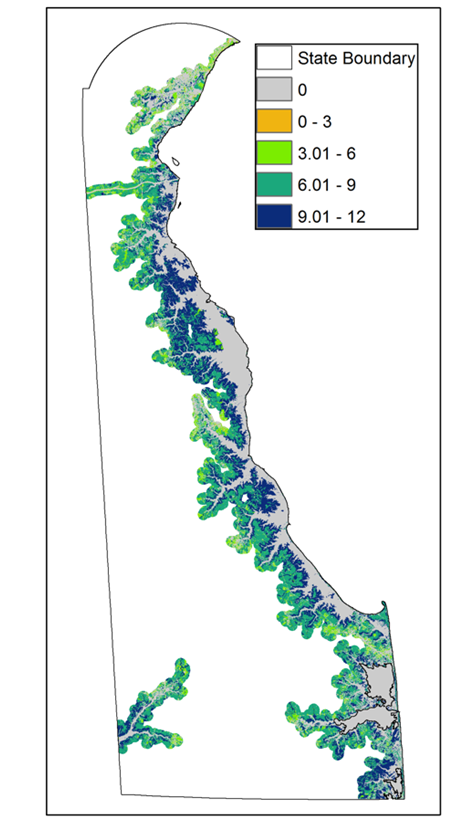

DNREC completed a mapping study in 2017 to model and predict the most suitable habitat for tidal wetlands to migrate into. This model is built from many different mapping layers including sea level rise estimates, soils, slope, land use/land cover (LULC), elevation, and existing wetlands. Model results identified 26,391 acres of highly suitable lands along existing tidal wetlands under a 4ft sea level rise scenario (Figure 2). That represents the best of all suitable habitat statewide, to narrow our focus to priority areas.

Mapping suitable habitat was step one. Diving into the results came next. Where are the best areas for wetland migration? Who owns these properties and what kind of land use are they currently in? Most importantly, what steps come next for management? For starters, 84% of the 26,391 most suitable acres were in Kent and Sussex Counties. We found that only 40% was publicly owned or otherwise protected, leaving 60% in private ownership. One third of the best migration habitat is currently in agriculture, 13% is currently forested, and 43% are already wetlands but freshwater, meaning they would undergo a major wetland change in the future. All of this is helpful as we work on the next steps which include education, outreach, messaging to landowners, and working with state and federal agencies to plan ahead.

DNREC is now refreshing this model with the most current data layers. For example the wetland, LULC, and soil layers have all been updated since 2017. Working with Delaware Coastal Programs staff, the model was rebuilt and rerun, and draft results are currently being reviewed. Look for results and a report later this year.

Written on: March 24th, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Animals

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Ah, the start of spring. We all have our own personal odes to season. Many of us wait for that 70-degree day, some prepare gardens for planting, while others set the date to do that annual “cleaning” and get the dust off their ceiling fan blades. For us, one of the most indicative signs warmer days are approaching are the sounds and sightings of frogs.

These amphibians live in habitats across the United States and are clocking in at about 6,000 known species worldwide. As we all probably know, frogs go through metamorphosis transforming from tadpole larva into an adult frog – quite the astonishing biological process. It’s even referenced in their group name, amphibian, coming from the Greek work amphibios meaning “double life”, as they live part of their lives on land and part of it in water. According to Jim White, Senior Fellow for Land and Biodiversity at Delaware Nature Society, one or more of Delmarva’s 18 frog species may be found in almost every natural terrestrial and freshwater habitat in the state. Let’s take a closer look at 5 frogs coming to a wetland near you this spring.

Green Treefrog (Hyla cinerea)

As an easily identifiable species, this frog ranges from bright green to dull green with a white stripe down its side. They prefer to live in marshes, swamps, small ponds and streams with lots of floating vegetation and grasses. Feeding mostly on small insects and invertebrates, green tree frogs are most active at night. Two unique features are its sticky toe pads and that they can make 6 different calls.

Southern Leopard Frog (Lithobates sphenocephalus)

With a powerful jump, this species can be found further away from water or a wetland as it forages for food. This species especially likes freshwater wetlands abundant in insects, arthropods, and worms. Adult frogs have two prominent yellow or gold dorsolateral folds, or ridges, extending from behind their eyes to their hips. They may be considered smarter than your average frog, as their eggs can hatch earlier than normal if predators are nearby.

New Jersey Chorus Frog (Pseudacris kalmi)

Look through sedge clumps and grass in shallow, wet areas to spot this species. New Jersey chorus frogs enjoy herbaceous vegetation in ponds and moist woodlands, using freshwater wetlands as breeding locations. Usually recognized by their linked lines in the shape of a triangle between the eyes. Their call can be heard day or night, and is similar to the sound produced by running your finger over the teeth of a comb.

American Bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus)

Ranking as the largest of the North American frogs, this species can weigh up to 1.5 pounds and reach almost 7 inches in length. They enjoy freshwater ponds, streams, and marshes with shoreline vegetation for habitat, and will primarily hunt at night. With fully webbed hind feet, bullfrogs can swim well and jump far. Not only are they athletes, but their call can be heard up to a half mile from their location.

Pickerel Frog (Lithobates palustris)

Often confused with the northern and southern leopard frog, this species has two distinct parallel rows of spots down its back. These vivid amphibians occur in a variety of freshwater aquatic and wetland habitats, like fens and forested streams. As a defense mechanism, they produce a toxic substance from their skin which makes them unappealing to most predators.

As with all things in the circle of life, frogs are an essential dweller of functioning aquatic, wetland, and riparian ecosystems. Tadpoles graze on algae, adults can devour thousands of insects annually, including those carrying diseases or sicknesses. Being both predator and prey, they serve a purpose for many species across the food chain, as well as many species across varying habitats. And the sound of calling frogs can be quite soothing at night. Becoming a frog enthusiast doesn’t require a college degree; if you’re a patient listener who enjoys the outdoors, these species can be heard and seen in action this spring.

You can attract amphibians to your yard by creating a habitat and supporting biodiversity. Build a pond, support your backyard marsh, plant native species – make a difference by letting frogs and amphibians thrive.

Written on: March 24th, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Natural Resources

By Eddie Meade, DNREC’s Shoreline and Waterway Management Section

If you head to the Delaware Beaches mid-March, you may notice something along the dunes. Rows and rows of young Cape American beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata) where there previously were none. Early every spring, the Shoreline and Waterway Management Section puts out a call to action and gathers volunteers from local communities to help plant beach grass along the Atlantic Ocean and Delaware Bay. To date, over 5 million stems have been planted.

But first, let’s back up a bit.

Who is this section of government involved with natural resources? And why is “Shoreline” (insider nickname) charged with the duty of planting beach grass in our dunes? Well, within the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC), there lies the Division of Watershed Stewardship, within which are are various sections and programs, one of which is the Shoreline and Waterway Management Section (SWMS). It’s a lot to keep track of. One of the many missions of this section is to maintain and improve Delaware’s beaches, shorelines and waterways. The section manages this mission through regulation of coastal construction activities and implementation of dune and beach management practices. Boom – that is where beach grass planting comes in. The plantings are a key component in protecting and enhancing eroded beaches to enable continued recreational use of our precious beach resource. In Delaware, this is a majorly important asset.

“Beach” means that area from the Delaware/Maryland line at Fenwick Island to the Old Marina Canal immediately north of Pickering Beach, which extends from the mean high water line of the Atlantic Ocean and Delaware Bay landward 1,000 feet and seaward 2,500 feet, respectively.

“Regulated Area” means the specific area within the defined beach that the Department is directed to regulate construction to preserve dunes and to reduce property damage. The regulated area shall be from the seaward edge of the beach as defined above to the landward edge of the third buildable lot in from the mean high water line.

The Importance of Beachgrass

Sand dunes, by nature, are unstable and shapeable. They are frequently subjected to strong winds and high tides, as well as coastal storms intensified by the climate change crisis. Dunes themselves have the heavy responsibility of being Delaware’s first line of defense against nor’easters, hurricanes, storm events, and erosion. These “big sand piles”, as some may call them, also act as major sand storage areas, helping to replenish the eroded beaches during storm events. An easy way to put it is without sand dunes, storm waves could rush inland and flood properties, damaging belongings as well as structures. This aspect of beach dune protection is not often thought about, and is something we don’t want to happen. Cape American beachgrass (Ammophila breviligulata) is a native plant, meaning naturally found in a region, that assists with stabilizing and building up the natural dune. The blades of grass grow outward to help trap wind-blown sand which can create new dunes and expand existing dunes in an area. In turn, this helps the dunes become more resilient and provide protection against damaging coastal storms by absorbing wave energy. When you walk out to the beaches in Delaware, you are usually greeted by a healthy, stable dune growing some beach grass.

Beachgrass Planting and Plugs

Planting beachgrass is a relatively straightforward process. The grass itself is dormant between October 15th and April 1st and should be planted during this dormancy. Beach grass is sold in bundles of culms, or stems, and can be hand-placed in holes along the designated dune area. At DNREC, we use a large number of volunteers to help at planting locations across coastal Delaware. Here is a breakdown of the planting process and methods.

Following these specific planting methods provides a number of critical benefits:

Where to Learn More

For us at DNREC, we were given the authority “to enhance, preserve, and protect the beaches in the state so they can be shared and enjoyed by all” by The 1972 Beach Preservation Act (7 Del.C. Chapter 68). The plan is to keep doing just that. Since 1990, DNREC has organized events and coordinated dedicated volunteers to participate in the annual planting. Even though the 2023 Beach Grass Planting is completed, stay up to date here for more information on volunteering as spring 2024 approaches. If you have any questions about the annual beach grass planting or beach grass planting in general, please contact either Jennifer Pongratz, Jennifer.Pongratz@delaware.gov, or Eddie Meade, larry.meade@delaware.gov.

To see what else SWMS does, check out this blog post from way back when about waterway management in Delaware. And remember, keep off the dunes and beachgrass – it’s the law!