Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube RSS Feed

Written on: March 22nd, 2021 in Wetland Restorations

Guest Student Writer: Ezra Kottler, The George Washington University

All over the world, sea-level rise is driving changes in natural habitats. Greenhouse gas emissions have brought about the warming of oceans and melting of glaciers such that global mean sea level is increasing over time and the rate at which it increases is getting steeper and steeper 1. The Mid-Atlantic region is a particular “hot spot” for sea-level rise because of additional local conditions that include:

Due to the fact that the coastal Mid-Atlantic is flat and close to sea-level, a few inches of increased water can significantly increase the frequency of flooding from hurricanes and tropical storms. Not to be forgotten, another major outcome of sea-level rise is large scale habitat changes through marsh migration.

How can habitat migrate?

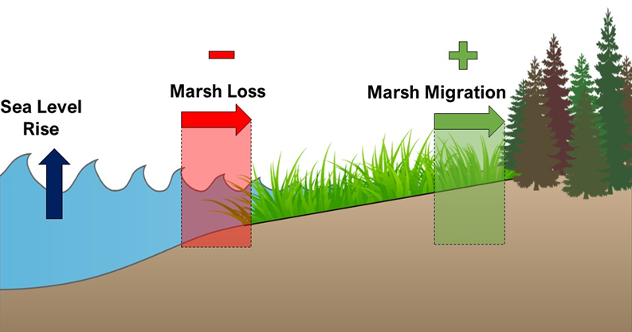

When we say marsh migration, it means something a bit different than animal migrations like monarch butterflies or blue whales. Marsh migration is a process of non-wetland coastal plants, like pine trees, dying due to storms and saline soils at the marsh boarder, then marsh plants growing in their place. This is a natural process that has always taken place a bit at a time, but in recent decades it has begun to speed up with sea-level rise. The ghost forests of dead pine trunks show the impacts of climate change here and now in our region 3, but marsh migration also provides hope. Marsh migration can actually help counteract the loss of marsh habitat that is drowning with higher sea levels, thus preserving important ecosystem services.

Our lab is studying what changes are happening at the moving border between marsh and the pine forest habitat. A major part of my graduate study research is looking for changes to the growth and success of salt marsh hay (Spartina patens), a native marsh grass, as it migrates into coastal forests. Salt marsh hay is a foundation species, meaning it creates physical conditions that allow other organisms to survive under the harsh conditions, like hot and humid salt marshes. Its presence on the landscape reduces water loss under the hot summer sun, provides food and hunting grounds for a diversity of animals, and critically, serves as the only suitable nesting habitat for many native and endangered shorebirds 4. But as salt marsh hay starts growing in the forest understory, and is released from the stress of sun and salt, the species faces a new challenge. With little to no light at times during the seasons in the forest understory, salt marsh hay has difficulty getting enough light to do the photosynthesis needed to keep food (in this case glucose) on the table.

For the past few years I have carried out a series of experiments growing salt marsh hay in different environmental conditions. When grown under the limited light conditions of canopy, salt marsh hay grows longer stems and wider leaves to maximize how much surface area it can use for photosynthesis. This is similar to what happens to lettuce and other garden greens when you grow them under a shade cloth. At the same time, salt marsh hay makes fewer roots and stems, and is unable to flower when shaded by the pine tree canopy. This might be a problem for shaded salt marsh hay populations, as they must rely on growing new stems to expand their distribution, and cannot produce seeds.

But there is also reason for hope: salt marsh hay seems to be very flexible in its responses to the environment. When individuals from the forest were grown in the marsh, they rapidly grew more stems and roots, growing more robust. Our management decisions in these transitional coastal areas can help facilitate the migration of native marsh species over invasive species. By making the best management practices for our ecosystems, we can enjoy the beauty and benefits of marshes for generations to come.

References

1 Nicholls, R.J., Cazenave, A., 2010. Sea-Level Rise and Its Impact on Coastal Zonea. Science 318, 1517-1520. https://doi.org/10.1126/science,1185782

2 Piecuch, C.G., Huybers, P., Hay, C.C., Kemp, A.C., Little, C.M., Mitrovica, J.X., Ponter, R.M., Tingley, M.P., 2018. Origin of spatial variation in US East Coast sea-level trends during 1900-2017. Nature 564, 400-404. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0787-6

3 Gedan, K. (2021, March 16). Ghosts of the Coast. Retrieved from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/12863715c76a40d8928e467845801b03

4 Wilson, M.D., Watts, B.D., Brinker, D.F., 2007. Status Review of Chesapeake Bay Marsh Lands and Breeding Marsh Birds. Waterbirds 30, 122-137. https://doi.org/10.1675/1542-4695(2007)030[0122:SROCBM]2.0CO;2