Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: July 13th, 2022 in Wetland Assessments

By Brittney Flatten, DNREC’s Watershed Assessment and Management Section

This summer, the Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program (WMAP) team is doing wetland condition assessments in the Pocomoke River watershed. During an assessment, scientists look at soil quality, rate sources of water, evaluate the plant community, and identify stressors in or around the wetland. These observations help determine if the wetland is healthy and functioning. This work is part of WMAP’s ongoing project to assess wetlands in every watershed in Delaware and the Pocomoke is last on the list! Because the Pocomoke watershed is a small and relatively remote part of our state, it doesn’t always get the attention it deserves. Let’s take a moment to learn about some unique natural features in this part of Delaware.

Plant Communities in the Pocomoke

The Pocomoke watershed is home to the Great Cypress Swamp. According to Delaware Wild Lands, it is the largest freshwater wetland and contiguous block of forest in Delaware. At its largest, it was probably 60,000 acres, but much of that has been lost due to timbering and drainage for agriculture. A few years ago, our blog featured a post from Delaware Wild Lands about wetland and habitat restoration in Great Cypress Swamp.

As you might’ve guessed from the previous fact, some swamps in the Pocomoke watershed have bald cypress trees. Bald cypresses tolerate being partly submerged in water so they can live in very wet conditions. You can spot cypress trees in wetlands by their knees- woody structures that grow aboveground. Scientists haven’t reached a consensus on the purpose of knees, but one hypothesis is that knees help provide extra stability in soft, wet soils. For even more support, bald cypress trees have buttressed roots which flare out at the bottom of the tree compared to typical straight trunks. Bald cypresses are also deciduous conifers, so they drop their needles every year unlike evergreen conifers which keep their needles year round. The Great Cypress Swamp and Trap Pond State Park in the neighboring Nanticoke watershed are thought to have some of the northernmost natural bald cypress stands in the United States. These unique ecosystems are much more common further south in the Carolinas and Louisiana, but you can find them right here in the first state!

You may come across Atlantic white cedar swamps in this part of Delaware too. These swamps typically have a mix of Atlantic white cedar, gum, and maple trees. They are important habitat for sphagnum moss and even rare insect-eating carnivorous plants!

Want to explore other plant communities in Delaware? Check out University of Delaware’s Statewide Vegetation Community Map.

The Deep and Dark Pocomoke River

The mainstem of the Pocomoke River is known for its dark and sometimes mysterious appearance. The small headwater tributaries are in the Great Cypress Swamp, but further downstream before draining into the Chesapeake Bay, the Pocomoke can reach depths of 45 feet, which is rare for a river that is less than 100 feet wide. Most of Delaware and Maryland’s eastern shore are in the coastal plain ecoregion, where land is flat and near sea level, so rivers have a low slope and move slowly. When combined with the presence of large, forested wetlands, conditions can create blackwater streams. The leaf litter from cypress and cedar wetlands decomposes very slowly in low-oxygen waters and releases tannic acid into nearby streams, which gives the water its dark, yet clear appearance. Blackwater streams will naturally have lower dissolved oxygen and are more acidic, but there are still plenty of fish, reptiles, and amphibians that like to hang out in these ecosystems.

Preserving the Pocomoke

DNREC scientists in the Divisions of Watershed Stewardship, Fish and Wildlife, and Parks and Recreation all work to preserve unique natural areas in Delaware, through assessing wetland condition, documenting plant and wildlife communities, and protecting land with conservation areas, easements, and more. Non-profit organizations like Delaware Wild Lands and The Nature Conservancy work to preserve and restore cypress and cedar forests in Delaware and Maryland’s lower eastern shore. You can get involved too by learning more about protecting Delaware’s wetlands and watersheds. If you want to see these cool ecosystems in action, visit Trap Pond State Park or Pocomoke River State Park in Maryland. You can also learn more on the Delaware Wild Lands page for Great Cypress Swamp.

Results from previous assessment years and watersheds can be found in our library.

Written on: July 13th, 2022 in Education and Outreach

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Science and reality of our current times shows that certain groups in society carry unequal economic and environmental burdens. The food we eat, the air we breathe, our water sources, and indeed our overall health depend on a clean and sustainable environment. Unfortunately, the benefits of an equitable life are not always shared. Many areas across the nation predominantly made of racial minorities and low-income communities still face challenges with accessing those everyday needs or environmental education. The movement in the United States, and really across the world, to recognize and protect the right to a healthy, clean, and sustainable environment is what is called Environmental Justice (EJ).

Environmental Justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of race, color, national origin or income, with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies; and the equitable access to green spaces, public recreation opportunities and information and data on potential exposures to environmental hazards.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Although this concept is being focused on now more than ever, the roots of EJ span back to the late 1960’s in the United States, primarily started by people of color. Events during the civil rights and social injustice movements ignited the concept of EJ on multiple levels of society – grassroots, locally, and regionally. The principles set forth stemmed from events such as when Latino farm workers in California fought for workplace rights and safety, or when African American students in Texas protested a city dump in their community. There was movement on the rise during that time that laid the foundation for more organized efforts by minorities to stand up and speak out.

EJ Across Nation

Environmental justice concerns exist all over the country, from urban areas to isolated rural towns. Many low-income neighborhoods and communities of color experience disproportionate impacts involving natural disasters, access to green space, and education. These wide-ranging issues contribute to the gap between “those who have” and “those who have not”. Certain areas may struggle with long-term sustainability, while others are left without the means to improve their situation or environmental education. Some of primary challenges communities at risk face involve:

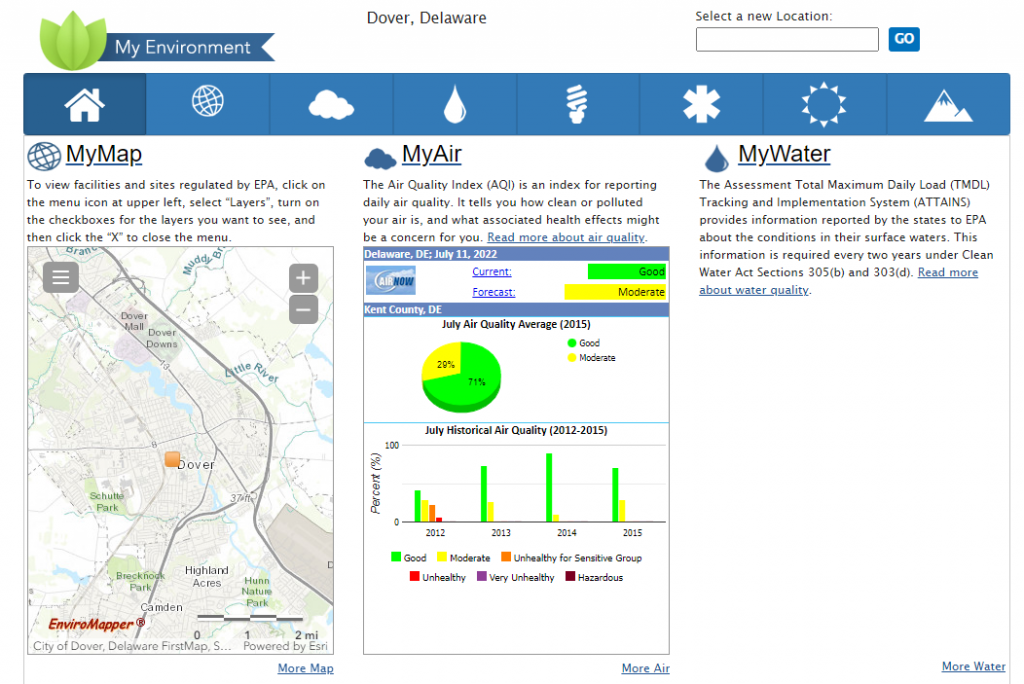

A key component in addressing EJ concerns is being able to identify the under-served and under-represented communities. On a national level, resources are emerging to ensure that people at risk have a seat at the table in their own future. The EPA EJScreen is an innovative tool that allows users to access a lot of environmental and demographic information in the United States. A user can identify anything from potential environmental quality issues to unemployment rates to traffic proximity. With the MyEnvironment tool, get as specific as your own zip code. This application is more than meets the eye when it comes to what you have access to; users of this tool can see over 60 different of categories of accessible data. Food waste, UV index, energy production, clean diesel programs, cancer risks, and surging seas just to name a few. On an individual level, states and organizations have developed similar mapping tools to focus in on what populations are at risk and what areas need the most change. Through these more specified datasets, stakeholders and community residents alike can expand there efforts into research or even policy. Current resources are out there waiting to be used, start with a simple google search to see what you find.

EJ in Delaware and with Wetlands

Let’s take it to more of a local scale. In Delaware, like many other places trying to navigate EJ, it is a work in progress. Though the first state is small, the variety of vibrant communities in each county deserves representation to the fullest.

A good place to start digging is the state of Delaware’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI). Social Vulnerability is the extent to which an area’s social conditions affect the response and prevention of natural disasters. With all the movement occurring with climate change and population booms in Delaware, the rankings calculated could help with future planning of socially vulnerable communities. DNREC currently has an internal EJ workgroup dedicated to actions and recommendations that address the areas of service, engagement and outreach. The group is even in the process of creating an EJ mapping tool with in-depth Delaware specific information. Other independent organizations have come out of the woodwork as well. Since 2011, the Delaware Concerned Residents for Environmental Justice has been taking a bottom-up approach of decision-making while trying to unite other grassroots and environmental organizations throughout the state. There are even partnership organizations, such as Healthy Communities Delaware, that feature missions involving work with the community rather than for the community.

When it comes to wetlands, integrating EJ practices into program development while focusing on meeting the needs of underserved communities is a critical tool to build wetland stewards. Vulnerable areas are exposed to social and environmental stressors, but have limited capacity to alter their relationship with them. An important step in the right direction is to empower the concept that anyone has the right to and can change their connection with the environment. Whether it be educating rural populations on wetland benefits, or speaking with urban planners about wetland adaptation and mitigation efforts, everyone has to be included in the conversation. Especially the populations experiencing the most discrepancies and challenges. These kinds of tactics can trickle over to wetland outreach, permitting, city planning, enforcement, you name it. Digital and on-the-ground tools can be utilized together to increase awareness of wetland ecosystems while reducing disparities. EJ provides inclusiveness for all to engage in and shape their understanding of wetlands and why to protect them. The ability to raise awareness about environmental degradation or inequities may very well elevate the voices most affected by them.

What Does The Future Hold

The importance of EJ spans far beyond the reaches of our country’s borders. In October of 2021, the United Nations Human Rights Council adopted a resolution recognizing that a healthy, clean, and sustainable environment is a basic human right. Recognition is the key word here. With more than 150 countries standing behind the concept of this inherent right, the United Nations General Assembly could bring about more ambitious and coordinated action to protect the environment for underserved and underrepresented communities. As the main policy-making sector of the United Nations, the Assembly can use this recognition at many levels of policy and law potentially creating government action and responsibility.

For those who have traditionally lived, worked, and played closest to sources of pollution or social inequalities, the stakes are high. An area’s ability to have successful business and economic stimulation, combined with a sense of representation, can go hand-in-hand with the well-being of its people. The history of the environmental justice movement has already proved that progress can be made with community advocacy backed by back science and the law. Bring in determination and innovation, and we’ve got ourselves a path forward for effective decision making. The dots have been connected. Whether it be in Smyrna, Delaware or Sir Lanka, EJ represents rights that should exist to all of us inherently. Who better to stand up for our communities than the people who live and thrive in them.

Want to see examples of EJ in action? Browse through the resources below to see what is happening across the United States.

Written on: May 25th, 2022 in Wetland Animals, Wetland Research

By Kayla Clauson, DNREC’s Watershed Assessment and Management Section

Wildlife cameras are a tool scientists can use to collect wildlife field data. Often, scientists go out in the field and conduct monitoring that gather similar data but are restricted because they only get a small snapshot of their target observations. For example, a field crew will observe all birds using a salt marsh during marsh bird surveys, which are conducted early morning at sunrise when there is low tide. This typically gets done three times a year, when birds are likely to be most active. Using wildlife cameras allows scientists to capture birds that are using the project area during the entire year, all hours of the day and night. Although wildlife cameras are not a perfect tool, they allow scientists to actively capture data with minimal disturbance to the animals as well as gather data over a longer period.

The target of this monitoring is to better understand wildlife habitat utilization at both our reference (salt marsh) and project (mudflat) sites. The goal is to see how animal usage may compare long-term between the two sites before marsh recreation occurs (current), during the reconstruction and afterwards. To get a better understanding of the entire project and other current monitoring, check out this previous blog post.

Our wildlife cameras have captured a variety of both mammals and birds. Let’s take a look at the birds we’ve captured for now.

Duck, Duck, Goose…

Family: Anatidae – Ducks, Geese, Swans.

Although waterfowl aren’t the primary targets of this study, we capture a lot of interactions of birds in the Anatidae family. Some of the common Anatidae family we’ve captured are Canada Geese (Branta canadensis), Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos), Green-Winged Teal (Anas crecca), and Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus). These birds can be seen mostly around high tide, while swimming or eating.

Anatidae Highlight

There has been a Canada goose pair nesting at our reference site. They have been named Honk and Tonk. Honk is the male goose (gander) and can be distinguished in most of the photos as he is a fierce protector of his female partner, Tonk. While she is incubating, she won’t be leaving her nest often until her eggs hatch. Since they are nesting in front of the camera, many of the captures at this site will be of them and can skew our data. However, scientists can use their best judgement on data recording of these two individuals.

What’re you laughing at?

Family: Laridae – Gulls, Terns, Skimmers.

The second most common birds we see a lot of are gulls and terns. Gulls can be seen in the project area mostly at low tide foraging on the mudflat. Gulls can be challenging to identify due to similar morphology, coloration, and juvenile plumage. For data collection gulls were identified down to their family name (Laridae), except for Laughing Gulls (Leucophaeus atricilla). Named for their laugh-like call, Laughing Gulls are easily distinguished from other gulls because of their black head. In addition to Laughing Gulls, some common gulls and terns include Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus), Ring-billed Gulls (Larus delawarensis), Forster’s Tern (Sterna forsteri), and Common Terns (Sterna hirundo).

Laridae Highlight

Terns are known for their aerial dives when foraging for fish below the waters surface. Although terns are not typically found walking around the mudflat like gulls, we’ve been fortunate enough to capture some of their aerial dives on camera with a big splash!

Heron Paparazzi

Family: Ardeidae – Herons, Egrets, Bitterns

The third most common family we observe are herons and egrets in the Ardeidae family. One of our most seen birds during our monitoring are Great Blue Herons (Ardea herodias). We’ve also captured Great Egrets and Snowy Egrets- but with a lot less captures. We hope as the cameras remain out, we will capture more secretive marsh birds, such as the Least Bittern or American Bittern.

Ardeidae Highlight

Standing about four-feet tall with a six-foot wingspan, Great Blue Herons are quite the impressive bird. Known for their huge size and stalking behavior alongside coastlines and waterways, they also turn out to be quite photogenic. Many photos captured include Great Blue Herons observing the cameras closely, seemingly posing, or showing off the large fish they can catch.

Talon-ted birds

Family: Accipitridae- Hawks, Eagles, Kites

The last birds to discuss that are often captured in our project are hawks and eagles. We are fortunate enough to have captured Northern Harriers (Circus hudsonius) and Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). We see Northern Harriers flying low along the marsh looking for prey, such as small mammals, in the grasses. Bald Eagles can be spotted soaring with fish or showing off their talons.

Accipitridae Highlight

Best known for their patriotic symbolism for the United States of America, Bald Eagles are a frequent capture at our reference and project sites. We can distinguish both adult and juvenile Bald Eagles from each other based on the coloration of the feathers. Adult bald eagles are dark brown with a white head and tail, whereas juveniles are fully brown in coloration and do not have a fully white head until about 5 years of age.

Birds of a Feather

Some other birds we capture are Yellow Legs (Tringa melanoleuca), Clapper Rails (Rallus crepitans), Turkey Vultures (Cathartes aura), and Cormorants (Nannopterum auritum). Yellow legs belong to the family Scolopacidae, while Clapper Rails belong to Rallidae. These are both birds that directly utilize the marsh for hiding and foraging. Cormorants in the family Phalacrocoracidae are seen swimming at high tide and Turkey Vultures in the family Cathartidae are seen scavenging for food.

Stay tuned to learn more about what we capture on our wildlife cameras next time when we explore mammals on the marsh!

Written on: May 25th, 2022 in Wetland Assessments, Wetland Restoration

By Erin Dorset, DNREC’s Division of Fish and Wildlife

The Inland Bays are a beautiful and beloved part of Delaware, containing about 20% of the state’s wetlands. Those wetlands are important economically, culturally, and ecologically, as they improve water quality, support commercial and recreational fisheries, support tourism, absorb flood waters, and provide crucial feeding and nursery habitat for wildlife. However, the Inland Bays are also home to agriculture and booming development, and sea-level is projected to keep rising in the region, all potentially having negative effects on wetland acreage and health.

In light of all this, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program (WMAP) recently investigated the major problems that wetlands in the Inland Bays face and the best paths forward to ensure that wetlands in the bays are around for generations to come, creating an Inland Bays Wetland Restoration Strategy. To do so, WMAP gathered relevant existing data and reports, including their own tidal and non-tidal Inland Bays wetland condition reports, used expert input to list out the major issues and potential solutions, and used GIS mapping software to identify prime spots where wetland restoration could make improvements.

The Issues

Within the Inland Bays Wetland Restoration Strategy, WMAP identified the major issues that tidal and non-tidal wetlands face in the Inland Bays. They include:

A Path Forward

After reviewing the worst issues that wetlands are dealing with in the Inland Bays, WMAP outlined tactics in the restoration strategy that are likely to be the most effective at tackling those problems:

Learn More

If you want to get into the weeds and know all the details, you can see the full Inland Bays Wetland Restoration Strategy, now publicly available! Spoiler alert: the full report contains information not only about tidal and non-tidal wetlands, but also about submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) in the Inland Bays, including widespread problems faced by SAV and tactics to address those issues. You can also explore maps showing potential wetland and SAV restoration areas on public, protected lands in the full report, such as the one shown here. Restoration maps presented in the strategy combined spatial data from the Delaware Watershed Resources Registry (WRR) with other existing spatial data, including current wetlands, highly suitable marsh migration lands, areas containing P. australis, and poorly drained agricultural or rangelands.

Written on: May 25th, 2022 in Education and Outreach

By Olivia McDonald, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

As you drive through the coastlines of Delaware and roll down your windows, you’re greeted by a view like no other. You spot an expansive marsh on your right, opening to a vast bay filled with boats and glistening with sunshine. Most of us know that feeling – you’ve made it to the coast. But let’s take a look beyond the beauty. Past your binoculars and deep within a coastal wetland habitat that is hard at work.

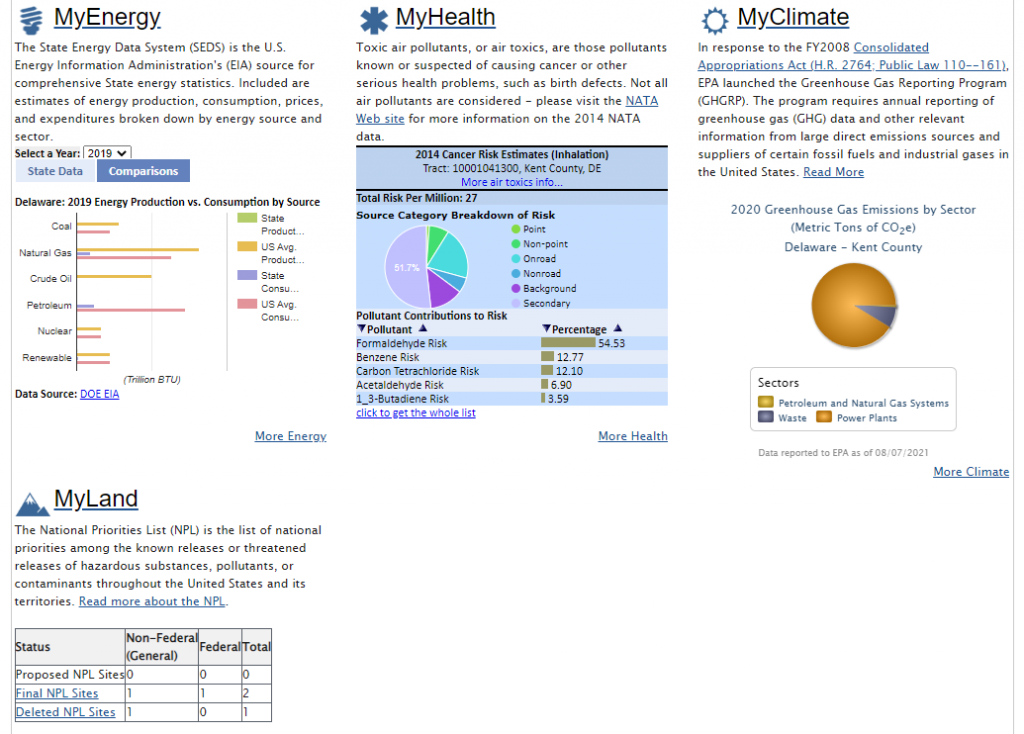

According the to Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), “Coastal wetlands include saltwater and freshwater wetlands located within coastal watersheds – specifically, USGS 8-digit hydrologic unit watersheds which drain into the Atlantic Ocean, Pacific Ocean, or Gulf of Mexico.” These land areas are permanently or seasonally inundated with fresh, brackish, or saline water. The plant community contains a variety of species that are uniquely adapted to the degree of inundation, the type of water that is present, and the soil conditions.

Don’t let the word “coastal” trip you up too much. In this case, we’re talking about wetlands that can be tidal and non-tidal, and freshwater or saltwater. Types of coastal wetlands include, marshes, salt marshes, seagrass beds, freshwater marshes, swamps, bottomland hardwood swamps, and mangrove swamps and forests. What is clear from Map 1 is that coastal wetlands can in fact extend many miles inland from the edge of the coast. Each wetland’s condition within the watershed depends on the influences and health of the surrounding watershed. Some of these areas are not small in nature, and can impact large portions of one or more states.

So what’s the big deal?

To understand the value of coastal wetlands, we need to understand the benefits. Ecosystem services can help us quantify those benefits that these habitats provide and show us how they impact our everyday lives. Let’s take a look at these essential services to people and the environment.

Clean Water

Ah, nature’s water purification system. Coastal wetlands, and really wetlands of all kinds, filter sediment and absorb pollution from outside influences. Runoff from hard surfaces, being a leading cause of pollution, is combated head-on through wetlands. Extra nutrients and pesticides contributed by development and agriculture are filtered out so they don’t enter local waterways. Wetlands simply trap and filter these impurities, helping maintain healthy waters.

Flood or Storm Protection and Erosion Control

If you live in Delaware, you’re going to really appreciate this one. Coastal wetlands are the first line of defensive during storms or floods for residential and commercial property. By holding back amounts of floodwaters and slowing the rate that water enters a system, wetlands can reduce the severity of negative impacts from severe weather events. Coastal wetlands can also prevent coastline erosion due to their ability to absorb destructive wave energy. Being able to dissipate energy created by ocean waves or water movement helps to slow the degradation of a shoreline. For the first state this means protecting people, land, infrastructure, and agriculture from devastating damages.

Carbon Sequestration

As the effects of climate change increase, the need to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere becomes more vital for our planet’s future. Certain coastal wetlands, such as salt marshes and seagrass beds, play an important role in decreasing that release. It’s a term we call coastal blue carbon – carbon dioxide that is absorbed and stored in specific coastal ecosystems. These habitats capture and store the gas from the atmosphere in both plants and soil, and even sequester more carbon dioxide than they release. Though the science behind it all is intense, the results can be more simply understood. Coastal wetland ecosystems have a natural ability to reduce the effects of climate change.

Recreation and Tourism

Each coastal wetland is distinct in the habitat it provides, and those areas aren’t just for wildlife. Wetlands provide the public and landowners alike a myriad of opportunities for recreation. From bird watching to hunting, hiking to photography, these ecosystems open the door for people to experience nature. The ever-growing tourist industry centered around Delaware’s beaches do more than just trickle down to hotels, restaurants, and local businesses. With an intricate coastline stretching the length of the entire state, impacts from growth are being seen throughout all three counties. Our coastal habitats are a major economic drivers for a variety of communities job growth and revenue.

Sustainable Fisheries

Imagine your favorite seafood dish. Where do you think it comes from? Many kinds of fish – from salmon to striped bass, as well as lobster, shrimp, oysters and crabs – depend on coastal wetlands for places to feed, live, or reproduce. These areas are like nurseries for young commercial fish and shellfish species. What you see swimming as a little guppy in the back bays may in fact become a 15 pound Bluefish. Quantity and quality of species equals health and extent of wetlands.

Loop back around to Map 1 again and zoom into Delaware. The entire state (yes, the whole thing) is zoned as a coastal watershed. So all the wetlands within the 45 watersheds in Delaware are considered to be in coastal watersheds whether they are tidal or non-tidal. Due to their proximity and zonation, these particular wetlands are more at threat than others in the country, making them particularly important for protection.

Once a habitat is degraded or lost, it loses its value and can become costly to recover the benefits it provides. Using scientific research and extensive management can provide an assortment of recommendations to conserve or preserve these coastal ecosystems for the future. Projects and funding across the country are coming to fruition for wetland restoration involving local, state, and non-government organizations. But some of the most influential adaptations start with you. Understanding the functionality of these coastal ecosystems is a large step in the right direction. So next time you snap that photo of a sunset, or take a bite into a fried clam at your favorite restaurant, be sure to thank coastal wetlands; habitats too valuable to lose.

Written on: May 25th, 2022 in Wetland Assessments

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

The summer of 2019 was like most for the Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program field crew. Similar to summers before it since 2000, we had a selected watershed to focus on and call ‘office’ for the growing season. Field crews spend the summer visiting randomly selected wetland sites, ranging all types, located on public as well as private property. Our job includes trekking to each selected site and conducting a wetland health assessment; a checklist of wetland stressors that allows biologists to rate how well a wetland is functioning. Each site gets rolled together to produce an overall watershed grade which allows DNREC to rate and track how healthy and functioning Delaware’s wetlands are.

The Brandywine River watershed’s Delaware portion stretches from the Christina River to the Pennsylvania state line all the way across the arc- from the Delaware River to the notch. It includes some beautiful landscape but also a lot of highly developed land. Plus signs of topography! Coming from Dover, it was a change of scenery to have boulders and hills. We replaced the tidal wetlands of the coastal plain with groundwater seeps of the piedmont, and it made for an interesting summer- if you are a wetland geek, I guess, which I am.

We spent three hot months exploring the Brandywine watershed, navigating narrow windy roads with absolutely no shoulder, and scrambling up and down steep banks to finally assess 68 wetlands in total. The data we collected was used to rate the health of all wetlands watershed wide – which includes about 2,800 acres. All in all, wetlands in the Brandywine watershed earned a C+ grade. Not the worst but not the best. Here’s more on why they didn’t make the honor roll and how we can make improvements.

The healthiest wetland types were headwater forest flats and groundwater seeps, both earning a B-. Floodplain riverine and isolated depressions both earned C’s. Each wetland type was different in why they received their grade. Flats had excellent habitat quality but poor buffer quality due to development. Groundwater seeps had excellent hydrology but very poor buffer quality due to development. Riverine wetlands had good habitat and hydrology but poor buffer quality. Lastly, depressions had excellent hydrology but very poor buffer quality. All of this is captured colorfully on the Brandywine watershed report card.

Any good student would want to bring their grades up after mid-terms, so what can we do to improve wetland health? For all four wetland types, the category with the poorest condition rating was the wetland buffer, or area immediately surrounding. We can’t take away development that is already there but we can do things to protect wetlands and waterways from as many present and future impacts. Presently, landowners can maximize the protection buffers offer by planting more and mowing less- create a wide (50ft), thick vegetated area between yards or roads and wet areas. In the future, we need development to plan for a wide riparian buffer around wetlands and streams. This allows harmful chemicals and nutrients to be filtered out before reaching our waterways. It also provides rich and important plant and wildlife habitat.

For the full watershed health report visit: https://documents.dnrec.delaware.gov/Watershed/Wetlands/Assessments/Brandywine-Watershed-Condition-Report.pdf

Written on: March 17th, 2022 in Wetland Animals

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

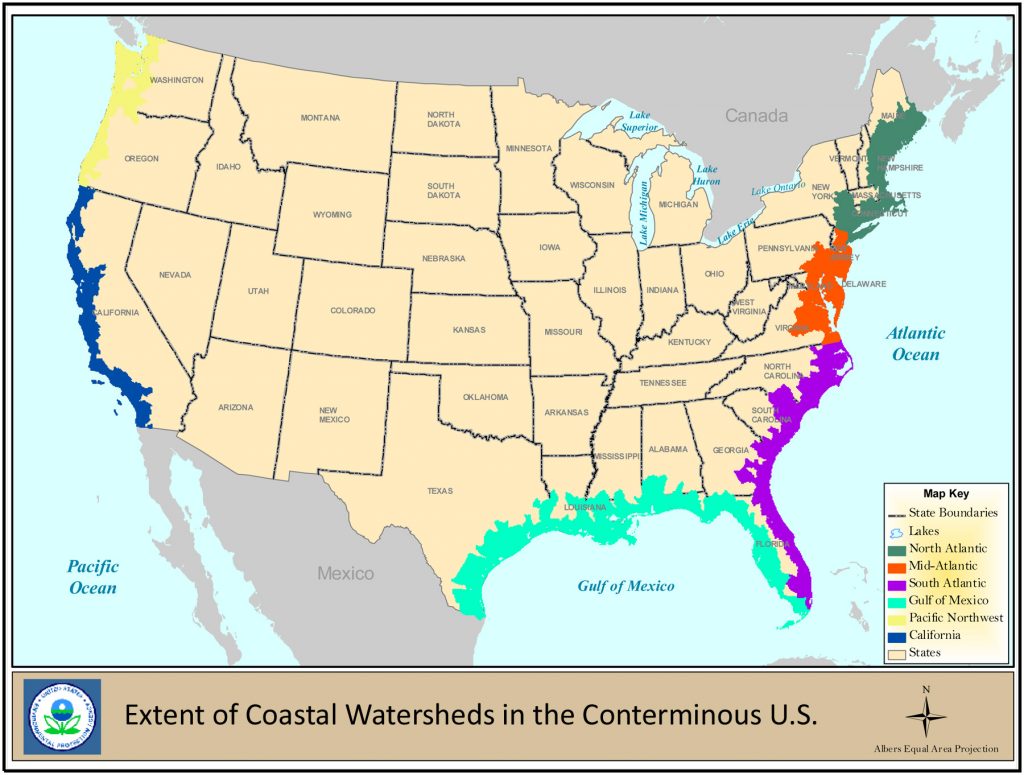

Early on a rainy but relatively warm February morning, while most people were still snuggled under the blankets, two biologists from DNREC Fish & Wildlife wade through a wetland pond in Blackbird State Forest. Their chest waders and raincoat keep them dry. Their headlamp helps them navigate in the early light around stumps and shrubs as they shuffle around the pond checking traps set the evening before. What are they after? The Eastern tiger salamander, one of Delaware’s rarest amphibians.

Today’s catch has been good, 100 individuals captured in this one large pond. There are several other ponds to check, yielding several hundred in total for the day. I pull up to the forest area parking lot hours later, well-rested, caffeinated, and ready to help with the detailed process of measuring and recording data on each salamander before releasing them. Life history data such as sex, length and egg bearing-status are recorded for each creature. A photo is taken as well, to be sorted and matched up with photos from previous years- a tedious task that helps biologists identify individuals by their markings.

All of this information is used to help DNREC count and track local populations of this state endangered amphibian. Timing is critical. Tiger salamanders are the first species to come out of winter brumation (that’s hibernation for cold-blooded species) in nearby forests to gather in vernal ponds to breed and lay egg masses. Their internal clock is motivated by warm rain in late winter to early spring. They may only hang out in ponds to breed for one or two weeks before heading back to upland forested habitat.

Tiger salamanders historically ranged from southern New York to northern Florida, but is now endangered in New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, is essential gone from Pennsylvania, and are of special concern in North and South Carolina. Their number one threat is loss of habitat. Clearing forests and removal of forested buffers around seasonal ponds leaves them no where to go. Although seasonal ponds normally dry up at the end of the summer, droughts and shifts in normal rain patterns due to climate change also increase mortality.

What can you do? Plant more trees! If you own forested property, leave logs and downed trees in place- they make good salamander hiding places. If you own a seasonal pond, be sure to keep a wide forested buffer around them. Resist the urge to clear and mow up to the edge. Lastly, encourage the protection of freshwater wetlands and buffers statewide and by county.

Written on: March 16th, 2022 in Wetland Assessments

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

By now, you may have read through our previous Status and Trends blog posts focused on current acreage, or status, of wetlands, as well as trends such as gains and losses. There is still one trends category to dive into: changes. This is probably the most difficult category for us to summarize and report on. It comes down to the details, looking back and forth from older maps and photos to more recent ones. It’s also the least intuitive category of wetland trends for readers to recognize. How do wetlands change? Why is it important to track if they are still wetlands? Let’s jump in.

The changes category focuses on wetlands that have, no surprise here, changed over time, in this case between 2007 and 2017. Their boundaries haven’t moved, that would be a gain or a loss. This category takes a closer look at how existing wetlands are shifting and why. This may seem like splitting hairs, but a total of 13,822 acres of wetlands changed from one wetland type to another from 2007 to 2017 statewide. That’s about 4.6% of Delaware’s wetlands statewide. Definitely a topic worth keeping track of.

Of those 13,822 acres, 6,169 acres of changes occurred in tidal wetlands (44%) and 7,652 acres (55%) were in non-tidal wetlands. We divided them into four groups, mostly using changes in cover or vegetation as an indicator. It’s interesting to think about what factors could lead to a wetland change.

Shifts in Water Type

This group covers two areas: changes in water regime from Palustrine (or freshwater) to Estuarine (saltwater) and changes in tidal pattern from nontidal to tidal. Changes in hydrology accounted for 2,100 acres and confirm to us that water levels are rising and saltwater lines are moving further and further inland. Exposure to tides and salt water permanently alters the plants and animals that can live there. In this group, we can see how the relatively rare tidal freshwater wetlands and being pushed further inland until they will become pinched out at the base of created lakes and ponds.

Vegetation Growth

While most changes were because of a loss of vegetation, we also documented a small amount of growth. Accounting for only 10% of overall changes, plant growth from muddy or bare bottom into emergent vegetation, or growth in lakes and ponds occurred equally in tidal and nontidal wetlands.

Vegetation Loss

Loss of vegetation made up almost 1/3 of all wetland changes and was seen predominantly in tidal wetlands (94%). In these cases, tidal wetlands used to have grassy emergent plants but changed into muddy or bare bottom areas. This could also be related to sea level rise and erosion. Once coastal areas are bare and lack roots to hold soils together, they are vulnerable to further erosion and loss of shoreline habitat completely. This is a natural process being amplified by climate change that is being documented at an alarming rate along the east coast.

Vegetation Shifts

Shifts in the vegetation community can go both ways; plants growing in and up but also plants dying off or back. This was the biggest group for changes, accounting for 44% overall, and 90% of the time occurred in nontidal wetlands. Succession is a natural process and can happen when a grassy wetland grows into scrub shrub habitat over time. Alternatively, as we see water levels and flooding increase, we also see vegetation dying off, reverting from a forested wetland to an emergent wetland, sometimes becoming an expanded floodplain along a river. Lastly, deforestation was also a major source of vegetation shifts in nontidal wetlands, stemming mostly from timber harvesting. Sometimes those areas recover and revegetate over the years but often suffer from the physical impacts of harvesting.

Although these changes may seem really detailed, they can help us track the less obvious processes affecting wetlands in Delaware. Perhaps the acreage in an area didn’t change much but the make up of those wetlands tell us they are going through a downward process towards a loss. Keeping trends straight between tidal and nontidal systems is important too, as we decide how to protect and restore them.

Written on: March 14th, 2022 in Education and Outreach

By Caitlin Chaney, Delaware Center for the Inland Bays

In the last 30 years, the population across the Delaware Inland Bays watershed has surged. The Inland Bays is a special place to live, but growing development brings challenges to the watershed and those who live within it. Climate change, sea level rise, and nutrient pollution all pose threats to the Inland Bays.

The good news is that everyone, including property owners, have the opportunity to help care for our shared paradise in a way that benefits the ecosystem and community. The Delaware Center for the Inland Bays (Center) recently published Protecting the Inland Bays: A Waterfront Property Owner’s Guide, an educational resource that addresses some of the most persistent threats facing the Inland Bays and their watershed. It offers guidance on how to protect and enhance properties while promoting healthy shorelines and nearshore areas, water quality, and habitats for both people and wildlife. Below is a summary of some of the guidance provided within the publication.

First Steps:

A critical first step is informing yourself of the rules and regulations regarding your property. The Center recommends checking your deed restrictions, reviewing the appropriate HOA governing documents (if applicable), and researching town and county ordinances and state regulations and guidance.

Minimize Runoff and Groundwater Contamination

Small adjustments on your property can make a big difference in reducing polluted stormwater runoff and groundwater. Here are some best practices:

Create Your Very Own Nature Preserve

You can help restore the delicate balance of the local ecosystem while creating a beautiful oasis right in your backyard.

Managing Septic Systems & Wastewater

Proper maintenance and management of your septic system and wastewater is essential to preventing contaminants and excess nutrients from entering groundwater.

These tips are just a few ways that property owners can simultaneously help protect the Inland Bays and their watershed and their investment. To access more in-depth guidance and information, including the benefits of living shorelines and enhancing buffers, please click here to download the Center’s waterfront property owner guidebook along with supporting resources.

Printed copies are also available upon request by emailing cchaney@inlandbays.org.

Written on: March 14th, 2022 in Education and Outreach

By Olivia McDonald, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Finally, it’s here! The holiday we all have never really heard of. It might be true that only folks working in the realms of nature know of this environmental festivity. So I figured hey, why not spread the word on something that actually impacts every single one of us – water.

World Water Day has been celebrated every year since 1993, and was created by the United Nations to celebrate water and raise awareness for people across the globe who currently are living without access to safe water. Now the words “safe water” can come in many different shapes and sizes. We are talking about things like drinking water, basic sanitation, bottled water, public facilities, surface, springs, recreational waters, the list really can go on. March 22 is the day, and this year’s theme of World Water Day is groundwater – making the invisible visible.

Right off the bat, let’s get started with some basics. What exactly is groundwater?

Groundwater is water found underground in aquifers, which are geological formations of rocks, sands and gravels that hold substantial quantities of water. Groundwater feeds springs, rivers, lakes and wetlands, and seeps into oceans. Groundwater is recharged mainly from rain and snowfall infiltrating the ground. Groundwater can be extracted to the surface by pumps and wells.

World Water Day 2022, United Nations

That definition gives me an overarching sense that what we do as humans on the surface matters underground. Since most of the liquid freshwater in the world is groundwater, choices big and small can affect things like farming, drinking sources, city sanitation systems, or animal populations. Countries with very arid climates often solely depend on groundwater for everyday use. Currently, the United Nations estimates that 40% of all the water used for irrigation of any type comes from aquifers created by groundwater – that is a rather demanding source! And of course to have a functioning ecosystem, such as a wetland or river, you need healthy water. Some of this may seem more like a third world problem, but impacts from fracking or places like Flint, Michigan show us that even in the United States water issues can become a major concern.

You might remember back in grade school learning about the water cycle, and how water in different forms takes certain paths yet is still all one thing. Well it really is. Lakes, rivers, ponds, streams, and wetlands are all within this hydrologic system of waters that are continually connected. When it comes to groundwater there is recharge and discharge. Recharge is when water seeps into the ground to replenish aquifers, and discharge occurs when water emerges from the saturated ground. Luckily wetlands do a little bit of both, but more often, groundwater discharges into our wetland areas. Either function the wetland performs adds value to the relationship of our water and land. Take a look at the benefits below;

Many places that the citizens of Delaware enjoy – publicly owned parks or state natural areas – contain water dependent on the success of this hydrologic system. In fact, most of the state’s public water supply comes from groundwater. Then we have our Category One wetlands which make up a small percentage of all of Delaware’s wetlands. These are very uncommon, unique freshwater areas like groundwater seepage wetlands. Seeps, as we like to call them, occur in areas on slopes or along slope bases where groundwater flows out onto the surface. Category One wetlands are home to complex habitats and rare plant and animals species, such as the Bog turtle (glyptemys muhlenbergii). I certainly want to keep that cute critter to the right around. As for humans, these wetlands are not only rich in plant and animal biodiversity, but also provide benefits for flood storage and water quality, simply through the groundwater coming to the surface naturally.

Honing in on groundwater for this year’s World Water Day means remembering that we need to strike a balance between the peoples’ needs and the planet. Continuous over-use of groundwater leads to the depletion of the resource. Overexploitation can lead to land instability and subsidence, particularly in our coastal regions of Delaware where salt water intrusion is occurring. Adaptation and policymaking should reflect the sustainable development for waters of all types. With the spotlight shining more and more on environmental changes, management and governance tools are being developed to combat the pressures of resource availability. Since groundwater is already so vied for, it is imperative to understand its role in sanitation systems, industry, agriculture, climate change, and ecosystems for the future.

Just because something is beneath the surface, doesn’t mean it has to be out of your mind. Wetlands and groundwater, like all the other wonderful natural resources we possess, are not infinite. It starts with you. In your backyard, in your reusable water bottle, in what kind of jeans you choose to wear (Google water and jeans, trust me). Calculate your water footprint to determine how your production and consumption choices affect natural resources. Clean up your local water source with a crew of friends. Every little bit counts, it doesn’t just have to happen on March 22.

To find out more about World Water Day, please visit https://www.worldwaterday.org/