Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: December 19th, 2022 in Wetland Animals, Wetland Assessments

By Brittney Flatten, DNREC’s Watershed Assessment and Management Section

For the past year, I’ve been working with another DNREC scientist to document submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) in Delaware’s streams, ponds, and bays to get a better understanding of where these plants like to grow and how we can protect them. I had previously observed some SAV in a nearby stream while doing a wetland assessment in Blackiston Wildlife Area and we decided to check it out. When we arrived, however, we were surprised to find that the stream barely had any water! Though the summer of 2022 was dry, the lack of rain didn’t fully explain what happened. So, we walked around for a few minutes to find more clues. We saw a lot of downed trees, but they hadn’t been cut down by humans or blown over by wind. Instead, most of the stumps had been sharpened into points like this:

Right away, we had a pretty good idea of what happened. The responsible party was Castor canadensis, a large rodent better known as the North American beaver. These furry creatures can be found here in Delaware, throughout the rest of the United States, and even northern Mexico. The beavers had built a dam upstream of our survey site, which altered streamflow in the area. While we didn’t find the SAV we were looking for, we stumbled upon an ecosystem undergoing a natural process of change, which was equally cool to see.

Why Do Beavers Build Dams?

Beavers have an instinct to modify their habitat by building dams. Scientists agree that beavers build dams to protect themselves from predation. Water builds up behind the dam, creating a pond. In the pond, beavers will make another structure called a lodge where they live, eat, and store extra food. Lodges have escape tunnels that allow beavers to exit into the pond if they are in danger. Plus, their large tails and webbed hind feet make them excellent swimmers, so predators like coyotes, bobcats, bears, and birds of prey have a difficult time catching them. Ponds also provide great habitat for aquatic plants which are part of the beaver’s herbivorous diet in addition to tree bark and leaves.

Beavers and Wetlands

Beavers are often viewed as a nuisance by humans because their activity can flood farmland and damage private property. However, beavers are a keystone species in wetland ecosystems since they are the creators of wetland habitat. Keystone species have a large impact on the wellbeing of other organisms, and their ecosystem would drastically change or cease to exist without them.

Just like other types of wetlands, excess nutrients created by beaver activity supply a variety of ecosystem services. Slower streamflow and dams trap sediment and nutrients in the pond, which prevents water pollution downstream. Dams in incised streams, where the water no longer reaches the top of the banks, can help reconnect the stream to its old floodplain. Deposition behind the dam and in the floodplain creates rich soils for wetland and floodplain plants, which serve as food and habitat for many different animals like turtles, frogs, birds, and insects. Compared to human-built dams, beaver dams are easier for fish to navigate while traveling upstream. Water storage in beaver ponds can help to maintain water levels during dry periods and lessen the force of floods.

Due to their importance, beavers are considered potential tools for restoration, particularly in the western United States. Structures that mimic beaver dams, which are called beaver dam analogs, or reintroduction of live beavers to an area are strategies that can be used to restore an impacted ecosystem to its previous function.

Where To Learn More

Since us humans and beavers share the same environment, we must work to find solutions that meet the needs of both populations. If you have questions or concerns about beavers in your area, you can contact your state’s fish and wildlife agency. If you live here in Delaware, you can visit DNREC Fish and Wildlife or call (302) 735-8683. The Beaver Institute has fact sheets and papers that cover a wide variety of topics relating to beavers and a list of resources to solve beaver-related problems.

Written on: December 19th, 2022 in Education and Outreach

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Ah, yes. The terrestrial ecosystem of bland, brown stuff. The innocuousness of peat may look like just any run of the mill soil, but this dirt is way beyond your average stuck under the nail type.

Peat, Peatlands, and Wetlands

First things first. Peat soil, or peat, is formed when an environment has a lot of water, low pH, low nutrient content, and low oxygen supply. All these factors come together to slow down an area’s plant decay and result in the build-up of partially decomposed plant remains in the form of soil. Peatlands are a type of carbon-rich wetland that accumulates layers of peat over time, and in some cases even thousands of years. These habitats occur in almost every country in the world and represent nearly half of the world’s wetlands.

How these habitats look on the ground is a bit more complex; every country is a little different. For simplicity’s sake, peatlands worldwide are commonly divided into bogs, fens, and mires. The water source, amount of water, and chemical composition of the water entering the system often determines the type of peatland in an area. Based on the map above, it’s clear that the majority of the world’s peatlands occur in the Northern Hemisphere, but don’t knock the Southern Hemisphere out completely. In cooler climates, such as the boreal regions of Canada and Russia, peatland wetlands are mostly the build-up of mosses, shrubs, and sedges. In warmer climates, such as Southeast Asia and Central Africa, tropical peatlands are in dense forested areas near low altitudes.

Why Do Peatlands Matter?

The naturally growing layer of organic matter (the peat) is the secret ingredient to this wetland’s importance. Since the plants in these habitats don’t fully decompose, the carbon dioxide (CO2) captured during photosynthesis actually becomes locked in the peat soil. These very specific water-logged conditions allow for peatlands to sequester, or capture and store, carbon that would otherwise be released to the atmosphere, contributing to global warming. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), peatlands currently cover around 3% of the earth’s land surface, but store around 33% of the world’s overall carbon, which represents more carbon than in all forests combined worldwide. Aka, they are the largest natural terrestrial carbon store. Here are some other benefits peatlands provide:

Peatlands in Delaware

A sight very rarely seen, peatland wetlands in the first state are seen in the form of fens. These non-tidal wetlands occur in deep, organic peat that is nutrient-poor and extremely acidic. Unique to the Delaware landscape, fens have standing water throughout the year and develop at the bottom of moderate slopes as groundwater is forced upward by clay soils. So where can you find these habitats? Well, you won’t see them at your local nature preserve trail. When we say rare, we mean it. Peatland fens can occur within two places in Delaware; complex stream corridors associated with Atlantic white cedar, and edges of salt marshes where there is acidic groundwater seepage. DNREC is still working towards accurately mapping the locations of these small, essential habitats to protect them and the sensitive species that call them home.

Threats to Peatlands and Their Future

In the past, the mining and burning of peat as a fuel was used in many developed countries which we learned was a big no-no. But today those same countries still use peatlands for agriculture, forestry, and horticulture. When drained or burned (as wetlands sometimes are) these areas transform from carbon sinks to carbon sources. What this means is that the large amounts of carbon that were being stored within the peat soils is being released back into the atmosphere. As the peat is exposed to air and releases its carbon in the form of CO2, it comes out around 20 times faster than it was sequestered. Yikes. The United Nations Environment Programme estimates that 10% of all annual fossil fuel emissions are from drained and burned peatlands. The effects of this problem can trickle beyond carbon emissions. Science has already seen increases in carbon footprints, reductions in land surface, increases in flooding, the thawing of permafrost causing peat to dry out, and increases in dry land creating potential for wildfires.

The good news is all hope is not lost. First and foremost, peat is not a renewable resource, it’s a fossil fuel. If there is anything the current climate emergency has shown us, it’s that using fossil fuels has had bad environmental consequences. On the ground level, do your homework on where everyday products or items come from. Avoid purchasing wood, flooring and wood-based panels in particular, that are sourced from destroyed tropical habitats in places like Southeast Asia and South America. Stay up-to-date on mining activity and become informed on how to speak out against the destruction of Arctic regions for mining sources; some of the most popular minerals include coal, lead, nickel, and precious metals. Next up, let’s plan for the future learning from mistakes made in our past. A crucial way in doing this is through “good governance”, or more responsible regulatory framework and legislation, especially regarding non-tidal wetlands like peatlands. Upgrading permit regulations to protect these crucial habitats, as well as including what restoration may be required after their disturbance, is a key step in keeping them around for the future. And, as always, reduce your carbon footprint and emissions on a regular basis – calculate your carbon footprint and take action now.

The conservation of peatlands can not only reduce carbon emissions, potentially on a global scale, but increase biodiversity of flora and fauna. The restoration of these areas provides insight into new techniques for a sustainable future while reviving essential ecosystems that provide services for the people and planet alike. And hey if Alec Baldwin has something to say it could be worth a listen.

Want to discover more about peatlands? Browse through these organizations doing incredible wetland work!

| Global Peatlands Initiative | Wetlands International | Project Drawdown’s Peatland Protection and Rewetting |

| American Forest Foundation |

Written on: December 19th, 2022 in Education and Outreach

By Melanie Cucunato, DNREC’s Division of Parks and Recreation

Did you know that Delaware is home to 34 Nature Preserves?! …What even is a Nature Preserve you ask? First off, ouch. Second off, allow me to attempt to give you the cliff notes version of the History of Natural Areas and Nature Preserves in Delaware. Ahem.

In 1977, the Delaware Nature Society published the book Delaware’s Outstanding Natural Areas and their Preservation written by Lorraine Fleming. This book outlined 101 sites throughout the state that have extraordinary examples of ecological, historical, geologic, and/or cultural significance. Following the hype the book received, the Delaware General Assembly passed Delaware Code, Chapter 73: Natural Areas Preservation System in 1978. This allowed for four key things:

Since then, the Natural Areas Advisory Council and the Division of Parks and Recreation have worked together to protect over 7,000 acres of land, establishing 34 total Nature Preserves throughout the State that may or may not have public access. Phew, that was a lot. Did you get all that? Because there will be a pop quiz later….

But there was that phrase… “for future generations of Delawareans”. What does that even mean? Being from the generation between Millennials and Gen Z, I can’t even fathom what generations after Gen Z are going to look like, sound like, or what trends they will start that I will undoubtedly try to adopt as well in a sad effort to “stay hip and young”. I am sure that the people making decisions on which lands to protect back in the 80’s never possibly could have imagined the land they were protecting would one day have a 13-year-old filming a TikTok dance on one of the trails next to the then 150-year-old tulip poplar trees. But they still did it, and they did it for us “future generations” to enjoy however we wanted to.

I was curious recently about which Nature Preserve was the first and when it was dedicated. I found the Tulip Tree Woods and Freshwater Marsh Nature Preserves (both located within Brandywine Creek State Park) … and – get this – they were dedicated in 1982! I remember looking at those documents for a moment and realizing that it was their 40th Anniversary this year! How lucky is that? I immediately went into gear planning their birthday party.

On November 4th, 2022, the Brandywine Creek State Park staff, Delaware Nature Society staff, Managers of the Tree for Every Delawarean Initiative (TEDI) staff, and the past employees of the Division of Parks and Recreation who made all of this happen came together to celebrate the birthday of the Tulip Tree Woods and Freshwater Marsh Nature Preserves. The event included some joyful and appreciative speeches from Charles “Chazz” Salkin, the first Nature Preserves Manager, later Land Preservation Office Chief, and even later Director of the Division of Parks and Recreation, and Lorraine Fleming herself. Following the speeches, we planted 260 trees adjacent to the Nature Preserve to establish a new era of forest for “future generations”. This planting was funded by TEDI, Governor Carney’s plan to combat climate change by planting trees throughout the state for carbon sequestration. After a long morning of planting trees, our guests convened for lunch and shared the famous “Bobbie” from Capriotti’s Sandwich Shop. After lunch, the Brandywine Creek State Park Interpretive staff hosted a guided walk through the Tulip Tree Woods Nature Preserve to awe at the now 200-year-old poplar trees. The day was truly magical.

And so, dear reader, the point of this article is this: making conservation and preservation decisions today for “future generations of Delawareans” is a weird and abstract concept that I don’t think anyone can truly grasp. I mean, how did those key people in the 80’s truly know that their decision to protect an old growth forest like the Tulip Tree Woods Nature Preserve would result in a New Jersey native woman, who happened to land her dream job at DNREC as the Natural Areas and Nature Preserves Program Manager, becoming completely enamored with this State’s Preserves and throw them a birthday party 40 years later? Let alone, be handed to torch to continue to protect land for future generation.

With that, I wanted to say: if you are reading this and you have contributed to the preservation and protection of the State of Delaware’s outstanding piedmont, marshes, freshwater wetlands, coastal dunes, etc.: Thank You. I can only hope that I do half as good of a job as you all have these past 40-50 years and pass that on to my own next generation.

Thank you for your attention and Happy Holidays! Enjoy your time off visiting one of our 34 Nature Preserves (that has public access) throughout the State!

If you would like to know more about the Natural Areas and Nature Preserves throughout Delaware or just want to chat about what preservation work you have accomplished, please do not hesitate to reach out to me via e-mail at Melanie.Cucunato@delaware.gov or via phone at (302) 739-9039.

Written on: December 19th, 2022 in Wetland Assessments

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

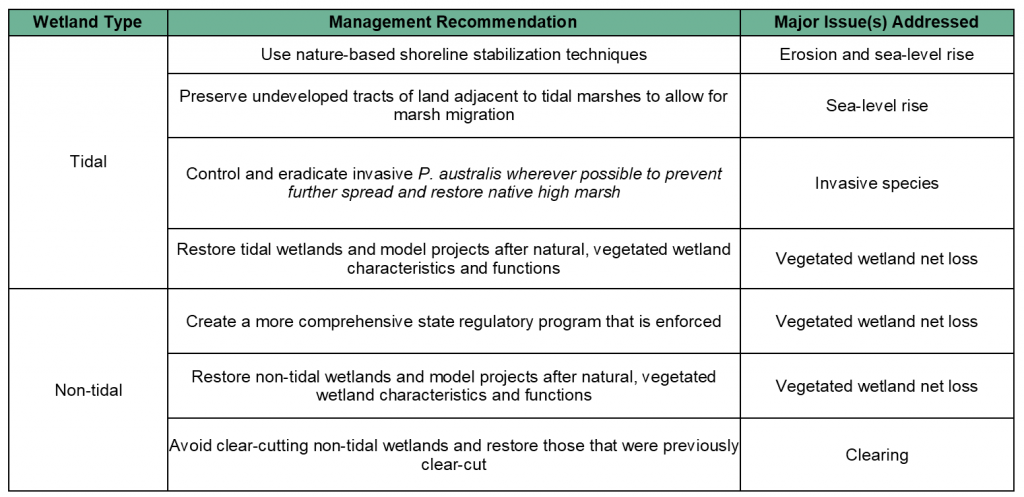

In this sixth and final installment in my Wetland Status and Trends blog series, I’m wrapping it all up with management recommendations. We came, we mapped, we calculated, we reported, now what? What comes next for wetland management and conservation in Delaware based on this project? Our recommendations stem directly back to the most prevalent causes for the recent loss of wetland acreage and function.

We offer seven main strategies for tidal and nontidal wetlands but the list could go on. You will notice that tidal wetland recommendations focus on addressing mostly natural forces such as sea level rise, subsidence and erosion. They are more innovation and capacity related areas of development. The bigger picture there is climate and consumption related Suggestions for nontidal wetlands, on the other hand, focus on limiting human impacts, making up for human impacts and prioritizing wetlands over money-making land uses.

On the tidal wetland front we are looking for more nature-based shoreline stabilization tactics to combat coastal shoreline loss. Delaware and DNREC is actively working on improving living shoreline practices and access but funding, landowner trust/perception, and technical expertise is still lacking. Next, we call for a step up in planning ahead for land conservation as sea level rise pushes marsh migration inland. Healthy wetlands can adjust themselves on the landscape to rising waters but only if natural, unhardened land awaits them, so strategic land preservation is key. Third, the war on invasive plants needs more support and more publicity. The Delaware Invasive Species Council and Senator Stephanie Hansen are helping raise awareness and encourage natives, but more aggressive and effective control of Phragmites is needed statewide. Fourth, it is important, as we document coastal wetland losses, that we have better capacity to restore tidal wetlands. Beneficial use is a complex tactic with a lot of potential to facilitate the return of eroded sediments back onto tidal wetlands. Beneficial use has not been widely demonstrated in Delaware so the legal and technical logistics are still evolving and DNREC supports more research and education.

In terms of nontidal wetlands, the recommendations are not new. The answers to our problems are us. For forty years, the documented loss of headwater forested flats has continued. As the urbanization of Delaware continues, seasonally unobvious and unregulated wetlands fall to land use changes such as timber harvesting, conversion to agriculture, and development. Our recommendation is for a comprehensive state regulatory program that also includes wetlands omitted under federal definitions. That includes effective enforcement and adequate mitigation for unavoidable impacts. Second, we want the field of wetland restoration be able to replace the wetlands being impacted and be restored in such a way that replaces wetland function. In this arena, more technical expertise, financial incentive, and landowner interest are needed. Third and final, we ask for timber harvesting to avoid nontidal wetlands, and to avoid clear-cutting. This includes recommending practices that leave the site hydrology intact and replaces vegetation with native species.

Above all, wetland conservation would benefit from better awareness, appreciation and prioritization of Delaware’s valuable resources. It’s difficult to hold back growth and gain but the long-term value of healthy functioning wetlands outweighs short term profits. DNREC is involved in moving several of these recommendations forward and we will continue working to improve wetland conservation and management through science and education, but we need help from many others.

Written on: September 26th, 2022 in Education and Outreach

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

For many of us about to read this blog post, we may not be artists at heart. In fact, some of us may have not picked up a paint brush or sculpting clay since middle school. Everyone has their niche, right? Luckily a benefit of modern times is being able to participate in cross sections of expression. Our appreciation of the natural world, much like the work of an artist, can be influenced by the mediums we interact with. Some artists prefer photography to charcoal drawing, just like some scientists prefer outdoors field work to structured lab procedures. Let’s go past the policy making and not worry about grant deadlines to take a look at the world of wetlands through a different lens: art making.

Nature and art both have an extremely long history of cultural attachment to our societies and livelihoods. Art itself is not only there to just make things pretty, but to make varying kinds of discoveries about subject matter. A great example are the prehistoric cave paintings at the early stages of human civilization. These pieces of art dating back anywhere from 40,000 to 70,000 years ago provide context to communication, as well as human’s relationship with animals and the environment of that time period. Both art and science were needed to fully understand nature and its effects on people.

If you have read some of WMAP’s previous blog posts, you’ll see that threats to wetlands include unsustainable urban development, agriculture, pollution, and invasive species, to name a few. But the biggest threat is one of perception. Promoting the understanding of these critical habitats requires a form “je ne sais quoi”, utilizing multiple forms of interpretation and communications skills. As we all know, changing people’s minds is no easy task. New perspectives or meaning can be found through an acrylic painting of a marsh in a museum or Excel-based table in a wetland report. The end goal can often be the same: moving society towards ecological understanding and even sustainability.

Here is a deeper look at artists of all kinds that are using their creative skills in support of preserving, restoring, and interpreting wetlands.

Heading south (far south) our first stop is in Costa Rica with landscape artist Tomas Sanchez. Originally from Cuba, this painter specializes in hyperreal art using a mix of memory and experiences to cultivate wetland images. Sanchez has been in the game for quite a long time having been around during the 1980’s when Cuban art was heavily censored. Since then, he has been painting to create remarkable images of wetland paradise to comment on humans interactions with nature and broader environmental issues. Not to mention, his recent set of works in 2022 are sustainably produced by Hahnemüle, a soon to be carbon neutral paper mill that uses reusable fresh spring water.

A true mix of public art and eco-conscious infrastructure is showcased with the art from Lillian Ball. As an art activist, Ball has an extensive background in providing commentary on environmental issues through solution-based approaches. Since 2007, her WATERWASH projects throughout New York state have incorporated artistic designs into stormwater remediation, wetland restoration, and outreach opportunities. From native plants to a water access park to green infrastructure for runoff pollution, her work can be applicable to wetland issues happening in communities worldwide.

Birds and landscapes are what bring our next artist pure bliss. Hailing from Ontario, Canada, Ron Plaizier has specialized in works of the 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional species while also incorporating landscapes throughout North America. Using acrylic paint on canvas or mason board, he captures the balance between human development and wildlife to showcase the results of conservation; up-close and personal images of wetlands species that reside in these ecosystems. Decorated for his efforts several times over the last few years, Plaizier is a signature member of Artists For Conservation and has even been featured Ducks Unlimited Canada’s National Art Portfolio donating artwork to help raise funds for wetland conservation.

Across the pond in the UK, an illustrator and paper artist Jessica Palmer spends time using her art to support wetland habitats, particularly with marshes. A combination of collage and paint are what express her support of environmentalism around the cities of Bath and London. Most notably, the collage works in Waterfields are a celebration of marshes and wetlands showcasing flora and fauna of her local area. Palmer also uses her papercut creations to provide intricate depictions of wetland wildlife at its finest. Having worked with the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust and Forest of Imagination there seems to be more to come from the layers and landscapes of this artist.

Ever heard of the Bayou Bienvenue Wetland Triangle? Well, self-taught naturalist and artist John Taylor has spent his entire life in the wetland system located in the Lower 9th Ward of New Orleans. Coastal Louisiana is made up of millions of acres of wetlands built over thousands of years by the Mississippi River. Unfortunately, Taylor has seen almost 400 acres of freshwater cypress-tupelo swamp become ghost swamp, and has witnessed catastrophic weather events in his community over the last 60 years. Photography, wood carving, and spoken word are John’s mediums of choice to create a platform to showcase the impacts of coastal Louisiana’s land loss. Though recently he has partnered with the National Wildlife Federation, Taylor is a lifelong advocate for wetland restoration plus a storyteller to visitors and locals alike.

Our last artist not only deals in massive works, but combines environmental activism with education. Based in New York, Mary Mattingly is an interdisciplinary artist who creates submerged buildings, sculptural watershed ecosystems, and even edible barges (yes, free floating food). Many of her art installations are centered around water resources and span over the last 20 years of the climate crisis. A notable floating sculpture, WetLand, integrates nature and a hand-built environment with importance of an equitable and sustainable water system. No medium is left unused with Mattingly as she offers specific yet Avant-garde solutions to environmental problems. With some works taking years in the making, her large-scale projects represent issues in climate change, sustainability, and human impact.

Being able to interact with all spectrums of nature gives us the ability to increase our connection to it. Artists and scientists alike can help us notice things in nature that we previously had not understood or were never taught to see. Through this collaboration of the arts and sciences, more space is made to change people’s values of wetland resources. Start Googling, see what’s happening at your local art league; be a part of another pathway towards preservation or action. After all, not all wetland warriors have to wear hip waders and carry a clipboard.

Written on: September 26th, 2022 in Wetland Animals

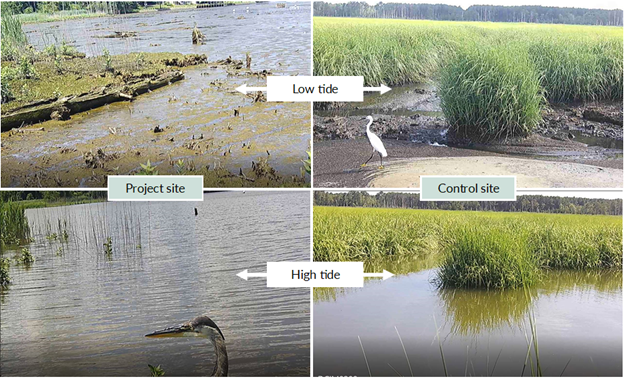

By Kayla Clauson, DNREC’s Watershed Assessment and Management Section

Wildlife cameras are a tool that scientists can use to collect wildlife field data. Discussed previously in a past blog post, wildlife cameras allow scientists to collect field data secretly, without being there, round the clock. This wildlife habitat utilization monitoring is part of a salt marsh recreation project, and supplements other ongoing monitoring that includes nekton sampling, breeding songbird surveys, vegetation, and wetland stability monitoring. Data collection for the project actually takes place within two Delaware salt marshes. One of the sites is where restoration will occur, in which we aim to rebuild a salt marsh where one used to exist. The other site is a healthy marsh and acts as a control. Scientists want to study the changes in habitat and wildlife utilization between both the sites and track any changes that may occur over time at the restoration site.

Each wetland experiences a semidiurnal tide, undergoing two high tides and two low tides daily. The animals that utilize these areas vary depending on time of day as well as the tides. See some differences between high and low tide at both sites below:

Family: Canidae – Fox and Coyote

Although secretive and swift, we’ve captured canids on our wildlife cameras. Canids are mainly nocturnal, and typically are seen during low tides that occur overnight and/or early mornings before sunrise. Two specific canids we’ve witnessed are Eastern Coyote (Canis latrans) and Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes). Because night-time shots are black and white, there are challenges when identifying these animals that have similar features. With assistance from specialized biologists, we were able to identify some of the canids as being the less-common coyotes. Coyotes are only present at our study site. The majority of the canid-captures are red fox. We’ve been fortunate enough to capture persistent interactions between a nesting Canada goose pair and a red fox (If you remember my previous blog post, Honk and Tonk had their work cut out for them defending their nest!). Red fox is present at both salt marshes.

Family: Procyonidae – Raccoon

These furry foragers are seen during similar times as the canids – coming out to eat at night during low tides. Raccoons (Procyon lotor) are omnivorous, eating both plants and animals. They can easily forage for food due to their very functional hands. In the salt marsh they are seen mainly feasting on crabs, shrimp, and fish they catch in the shallow low tide waters. If you observe the pictures closely, you can see how muddy the raccoon gets while walking around foraging in the mud. Raccoon have been seen at both our salt marshes.

Family: Cervidae – White-tailed Deer

Commonly seen on the side of the road grazing on grass, white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) often frequent the marsh for food. If you are confused how a deer gets to a more remote part of a marsh, you’ll be surprised to know that they are great swimmers! They are indeed very strong swimmers and have been recorded swimming up to 10 miles at a time. Young bucks and females have been spotted on our camera traps, utilizing both of our salt marshes. We were also lucky enough to see a rare piebald deer, with white and brown markings on her body. Piebaldism is a genetic condition that is expressed in about 2% of the white-tailed deer population- a pleasant find on our camera traps!

Family: Cricetidae – Muskrat

A semi-aquatic rodent, the muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) is often seen swimming or foraging within salt marsh waters. Although muskrat and beaver look similar, live in Delaware, and are both large rodents, they are not closely related. Muskrats are actually in a family with hamsters, voles, mice and rats, not beaver (family Castoridae). Muskrat can be seen at all times of day but have been captured mainly during nighttime.

Family: Mustelidae – Otter

More commonly found in lakes, rivers, and other freshwater wetlands, the North American River Otter (Lontra canadensis) has made an appearance at both of our study sites. There have been a pair of otter swimming and running in our tidal salt marshes. Another mainly nocturnal animal, otter was only captured in night time shots. Since otter are agile on both land and water, they’ve been seen both at high and low tides.

Other Mentions -Turtles and Tides

Although mammals and birds are the targeted species for this monitoring, there are other data that can be utilized from the cameras. For example, we can see the various turtle species enjoying our marshes as well. With the warming weather, turtles such as the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) and the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) have been spotted more and more frequently basking in the sun or enjoying a swim.

Cameras also provide insight to other important factors, such as vegetation growth, storm occurrences, and tidal range. Observing vegetation is a standard monitoring technique used in our tidal wetland assessments, so capturing photos that show vegetation growth over the year is helpful to gain insight to how the habitat changes. Lastly, we’ve captured the salt marsh providing one of its important ecological functions- by withstanding storms and protecting our uplands from flooding. We’ve captured large waves battering our marshes as well as excess water standing over the marsh following a storm.

Written on: September 26th, 2022 in Education and Outreach

By Ivette Clayton and Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Tax Ditch Program

What is a Tax Ditch?

Did you know that there are 234 tax ditch organizations across the state of Delaware? They make up approximately 2,000 miles of channels across Kent, New Castle, and Sussex Counties. However, not all ditches are tax ditches.

A tax ditch is an organization that is a governmental subdivision of the state. It is watershed-based and formed and run by the landowners who live within it. Each organization is provided technical and administrative assistance by DNREC’s Tax Ditch Program and county conservation districts.

Tax ditch watersheds range in size from a small two-acre system to the largest 56,000 acre system. The design of a tax ditch varies with most having a “u” or “v” shape. Some are big and some are small, but all have a permanent right-of-way to allow access and disposal for maintenance activities. Visit de.gov/taxditchmap to see if your property has a tax ditch located near it!

Why Tax Ditches?

Just about everyone benefits, either directly or indirectly, from tax ditches. It equates to just over 100,000 people and almost one-half of the state-maintained roads. The best part, tax ditch organizations are set up so that the landowners within the watershed are the ones making maintenance decisions. Who knows the land better than the folks living right there?

It should be noted that to have a successful tax ditch organization and operational drainage, active participation by the landowners is required. Volunteer positions, such as the Chairman, Manager and Secretary-Treasurer, need to be voted in annually, and appropriate tax rates levied to the landowners to ensure proper maintenance can be conducted.

Are you interested in volunteering your time as an officer? First, you have to be a landowner within the tax ditch organization you are interested in participating with. Second, reach out to our office at DNREC_Drainage@delaware.gov, and we’ll get back to you with more information!

Changing Environment, Changing Designs

Most of Delaware is flat with a high-water table so tax ditches were created to assist in moving normal water flows off lands. Most tax ditches were created from 1950 to the late 1980s, and land use has greatly changed since then. To account for this land use change, to have more resilient ditches, and to improve the health of our waters, tax ditch design changes are occurring.

Floodplain Benches

Floodplain or bankfull benches are becoming a method to address erosion issues and improve the stability of tax ditches. Instead of being a “u” or “v” shape, it opens the slope of the tax ditch channel. This nature-inspired design allows the ditch to hold larger volumes of water while maintaining the integrity of the bank. The shallower channel reduces the water’s velocity. A slower current deters the water from acting like a knife and cutting deep into the land, eroding the banks away. Slower water flow also allows sediment to settle out of the water, improving water clarity and quality.

Design updates to tax ditches like this improve wetlands and water quality but do require adjustments to the Right-of-Ways (ROWs) that run along side the tax ditches, as well as other properties in the watershed. By expanding the width of the tax ditch, it pushes the ROWs further into the adjacent land. This can cause changes on the land used and requires coordination with landowners.

Below is a cross-section of a tax ditch without and with a floodplain bench.

Below is an example of a floodplain bench that was installed in the Hudson Road Tax Ditch.

DNREC’s Drainage Program’s hope to help tax ditch organizations plan and construct stream restoration projects like this one to address maintenance issues in the future.

Written on: September 26th, 2022 in Wetland Assessments

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Over the past year plus I’ve written five blogs sharing the results of our 2007-2017 Status and Trends report which reviews many angles of Delaware’s wetlands based on analysis of the 2017 Statewide Wetland Mapping Project (SWMP). In this post I am focusing on final thoughts and discussion of everything presented. It’s a lot of information to boil down, so based on everything we found with wetland acreage, gains, losses, and changes what are the key takeaways?

Tidal Wetlands

On the tidal wetland front, net losses were around 100 acres and mostly due to environmental forces such as erosion and sea level rise, mostly in the Delaware Bay. This is similar to findings from 1992-2007. We documented a lot of tidal fresh wetlands becoming tidal as salt water lines creep higher and higher up tributaries, changing the wetland community over time. This shifting upstream of tidal fresh wetlands is vital to their survival and is only possible when tributaries are free flowing and not blocked by dams and control structures.

We also documented some tidal wetland gains as a result of marsh migration inland. This is a good sign that wetlands are attempting to seek new territory as sea levels rise. However, marsh migration only works if the wetland to upland border is not built up with berms or hardened by structures such as roads and bulkhead. This requires planning ahead and leaving room. Fingers crossed that wetlands can migrate as fast as sea level rise is coming behind them.

Not too bad so far, right? The more concerning discovery was that a significant portion of tidal wetland changes (65%) were due to vegetated wetlands turning into basically mudflats. They have not yet washed away into open water habitat but without communities of Spartina and other grasses their capacity to function drops way down. The next step here is being washed away completely so resilient shoreline stabilization tactics become very important to prevent future erosion and loss. We can’t stop sea level rise but we can slow down the impacts.

Lastly, improved mapping technology allowed us to label tidal wetland areas that were dominated by the invasive reed Phragmites australis. This feature allowed us to identify that over half (52%) of all high marsh areas in tidal wetlands contained or were dominated by Phragmites. Phragmites preys on recently disturbed areas, areas with altered water regimes and along the wetland to upland border. Once it takes over, it is very difficult to remove so prevention and control is crucial. This baseline reading will be useful to compare against in another 10 years.

Non-tidal Wetlands

On the non-tidal wetland front, the picture was definitely more bleak. Delaware logged a net loss of 2,534 acres of vegetated non-tidal wetlands between 2007 and 2017. Gross losses were even more. This is, again, on track with our findings from 1992-2007. The Chesapeake Bay basin bore the brunt of the losses, accounting for 62% of statewide totals even though the Chesapeake Bay basin makes up only 34% of statewide acreage.

Non-tidal wetland losses were associated with clearing for logging activities (54%), development (24%), and agriculture (19%). This pattern is consistent with non-tidal wetland losses from 1992-2007. A small portion were due to transportation and utility impacts (3%). Although timber harvesting is a renewable resource, impacts to wetland hydrology and habitat are significant and wetland function will take decades to become restored. Impacts to headwater forested wetlands were most common and leads to reduced ability to filter excess nutrients and pollutants from water moving through them.

Although the gross loss of non-tidal wetland loss was lessened by wetland gains, those gains were in the form of created stormwater ponds. In fact, 81% of non-tidal wetland gains were as unvegetated, open water retention ponds, usually in residential developments or on farms. Stormwater ponds offer severely reduced functions, providing limited wildlife habitat, water filtration and sediment retention services and are not an even trade for the loss of natural wetlands. Wetland creation should replace the impacted wetland type.

Changes for non-tidal wetlands were mostly (71%) related to a shift in cover types. For example from forested to scrub-shrub as a result of forestry clear cutting starting to recover or a scrub shrub area maturing into a forested wetland. Another portion of non-tidal wetlands (15%) changed from non-tidal to tidal fresh as the salt water lines creep further upstream and flooded conditions increase. This could cause forested wetlands to become emergent. Stands of dead trees in coastal areas, or ghost forests, are becoming a noticeable sign of salt water intrusion, sea level rise and a shift in forested communities.

At the end of the day, every wetland trend comes with an associated shift in wetland function. By far, Delaware lost more wetlands in ten years than were created and with those losses come a reduction in storm protection, erosion control, water filtration, water storage, fish and shellfish production, breeding bird habitat, and carbon sequestration. Created wetlands don’t provide comparable services and functions to natural wetlands and likely won’t for several decades. It is these long term functional impacts that we need to be thinking about in the next ten years and hopefully Delaware can break away from the trend of wetland losses that have been in place since the 1990’s and earlier. Small impacts here and there add up over decades and lead to a fractured resource network that cannot provide the valuable services that we expect to serve us for free.

Check back in December for the final post in this series focusing on what we do next with management recommendations.

Written on: July 13th, 2022 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Animals

By Laurel Sullivan, DNREC’s Delaware Coastal Programs

Attention! Calling all birders, experienced and newbies- the Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve (DNERR) has a Big Year challenge for you!

A Big Year is a challenge birdwatchers set for themselves to see or hear as many birds and bird species as possible within a single year. This is a personal goal or informal competition taken on by birders to see as many species and individual birds as possible within a given year and geographic area. DNERR is excited to host our own Big Year challenge in 2022 at our two locations, the Blackbird Creek Reserve and the St. Jones Reserve. Documenting the species of birds that visit the Reserves’ locations will allow us to collect data on common and rare species, while also increasing awareness about these estuary ecosystems.

Where Can You Bird?

The DNERR’s locations have dynamic habitats that offer many resources for a variety of bird species. The Blackbird Creek Reserve, located in Townsend, is a freshwater marsh with meadows and many native tree species that have been planted as part of our conservation and stewardship efforts. The St. Jones Reserve, located in Dover, is a salt marsh offering a preserved land area for many marsh birds. These two locations, with their differing habitats, resources and bird populations, will allow variety in the recorded sightings, helping our Big Year flourish! Both reserve components have walking trails available for birders to utilize while they are participating in our Big Year. The Blackbird Creek Reserve even has specified bird watching stations for visitors to make use of as they look for birds that may be wading in the Blackbird Creek.

What Birds Might You See?

Each of the habitats at DNERR’s locations have many resident species, which are birds that are commonly seen year-round. Some resident species are the American Robin, the Great Blue Heron and the Bald Eagle. However, the habitats also offer unique resources as the seasons change, attracting migratory bird species. DNERR does have some commonly seen migrating birds, such as the Red Knot, Dark-eyed Junco, and Canada Goose. By continually engaging with the public and the birding community, DNERR is hoping to capture the seasonal shifts of bird populations. We are also excited to document any rare species that may be sighted throughout the year. This information collected during the Big Year will help to inform restoration plans, land stewardship and conservation efforts.

How It Works

At the Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve, research is our middle name. That is where you come in. DNERR’s Big Year could not be done without the help of everyone who visits the Reserves’ locations. Participation in the Big Year is relatively easy; you do not have to be an experienced birder to get involved and become a citizen scientist – all you need is your smartphone. The Reserve will be utilizing two platforms – iNaturalist and eBird – to capture and record the data. The platform, iNaturalist, allows participants to upload individual sightings with pictures or audio. These sightings can then be verified and confirmed by other users and Reserve staff through the app. This makes iNaturalist a great option for beginning birders! The platform, eBird, commonly used by more experienced birders, provides an opportunity for users to populate a personal list of birds. Birders can use the Reserves’ hotspots to see recent sightings from other users as well.

While each birding adventure will be unique and your own, we ask that you follow the Big Year challenge rules below, which are based on the American Birding Association guidelines:

We want all birding participants to remain safe, please follow the safety guidelines below:

We at DNERR are very excited about our Big Year and the data that we will use for years to come to enhance our species inventory. We hope that this challenge inspires many new and experienced birders to explore the estuary. Become a Big Year Birder with DNERR today!

For more information about DNERR’s Big Year and how to become an official DNERR Big Year Birder, please visit our website. We look forward to seeing you out on our trails!

Written on: July 13th, 2022 in Education and Outreach

By Ashley Cole, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

This summer I’ve had the amazing opportunity to work with DNREC’s Department of Watershed Stewardship, specifically their Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program. I was very excited to get outdoors, see wild places no one has seen before, and keep our wetlands healthy. I thought these wetlands would be mostly free of trash based on how far away they were from where people would be. However, upon our first site visit of the season, all the way down in the Pocomoke watershed, I noticed the amount of trash that we found seemingly in the middle of nowhere. Our phones had no service and we were several hundred meters into the woods. How could trash have gotten there? I was shocked to find anything from candy wrappers to Royal Farms chicken boxes, to even old plastic soda bottles and cans. Seeing all this trash made me realize the damaging effects of littering and not disposing of trash properly. We all know that most waste leads to the ocean or other waterways, but to a wetland in the middle of the woods? Seems like there needs to be a change. As humans we often think that our small decisions have no actual impact on the environment. That if one person decides to do the right thing, it won’t make that big of an impact in the end. But believe it or not it can. All this trash that is being pushed into our wetlands came from somewhere and someone. If the trash would have been disposed of properly, it would not be in our wetlands.

The Importance of Wetlands

Wetlands play a key role in our everyday lives. Wetlands help prevent erosion of our shorelines, and help prevent flooding on the coasts as well as inland. Wetlands are home to so many important and beneficial plants, animals, and other organisms. Wetlands help remove pollutants from the water keeping our waterways clean. Wetlands also act as an air filter, grabbing CO2 and other air pollutants, like greenhouse gasses out of the atmosphere. As you can see, wetlands play a vital role in a healthy everyday life. But if trash keeps ending up in our wetlands, these important services will be diminished or eliminated. Wetlands choked with waste can hardly serve as good wildlife habitat. It is up to us to keep them clean and healthy.

The Impacts of Waste in Our Wetlands:

You might be wondering, how does a thrown-out plastic bottle, or a plastic shopping bag that end up in our wetlands cause any harm? Plastics are made up of many harmful chemicals that can be harmful to both human and animal health. When plastics are exposed to the sun they will begin to break down, the harmful chemicals will detach from the plastic and into the environment, this process is called chemical leaching. As the plastic is in nature, the plastic itself will also break down into small pieces called microplastics. Microplastics are increasingly becoming more of a threat to human and environmental health every day; it is in this form that plastics are even more dangerous and harmful. These microplastics end up in our oceans, being consumed by fish, which are then consumed by humans. Filling our ecosystems and food chains with harmful and toxic chemicals. These microplastics which leach even more harmful and concentrated chemicals can leach their chemicals into our groundwater and streams. Creating toxic drinking water for both humans and wildlife.

Other impacts humans have had on wetlands when it comes to not disposing of waste properly is by dumping waste fluids into the woods or in areas that is not seen by the general public, as an out of sight out of mind area where no one will care. Dumping harmful, and toxic substances, like oils, grease, and chemicals into the woods, has the potential to harm wildlife as they could accidentally consume it, get it on their fur or skin, or leach into the ground, poisoning the plants in which wildlife need to survive. These waste substances can also leach into the soil and down into our groundwater, once again causing a potential for harming the water quality of our drinking water, or the water quality of streams and oceans.

What You Can Do To Help:

There are many ways you can help keep our wetlands clean! One of the most impactful ways you can help decrease the amount of trash and plastics from entering our wetlands and environment is by decreasing your use of single use plastics. Fighting the war on pollution can start in the home! Before going to the grocery store, bring your own reusable bags to use instead of using the grocery store’s plastic bags. This can greatly reduce the number of plastic bags from being disposed of improperly that eventually end up in our natural areas. Decreasing the number of times, you eat at fast food restaurants who use products like styrofoam cups and food containers can also play a beneficial role in lowering the amount of trash in our wetlands. When purchasing soft drinks, try to find a store that allows you to fill up a reusable cup you had from home, rather than using a plastic cup they have in the store.

Of course, always disposing of your trash responsibly is a big one. Don’t litter and just leave your trash where it is. This is one of the main causes of how trash is ending up in wetlands. Trash on the ground can move into wetlands during storms due to runoff caused by rain or wind. By disposing of your trash properly, it will ensure that the trash is contained and taken care of responsibly. Another way you can help keep wetlands clean is by recycling the correct items that can be recycled. Always check the labels of plastics, papers, carboards, etc., that you are considering recycling. There are often different codes or ways in which an item can be recycled and identify if they can be recycled at all. By checking these labels and recycling properly you can help prevent trash and other pollutants from entering our wetlands.

When recycling, it is important to make sure whatever you are recycling is free from any left-over food debris and is cleaned out. When placing your recyclable items into your recycle bin or whatever you use to hold your recyclables, make sure that they are placed loosely into the bin and not bagged, as plastic bags cannot be recycled. Recycling is a very important effort that we can try to contribute to make Delaware and our planet a healthier, cleaner place. Recycling greatly reduces greenhouse gas emissions from entering our atmosphere, it conserves our natural resources and energy, and it helps keep our planet clean from not placing even more trash into already full landfills and trash dumps.

There are also plenty of useful and innovative ways you can reuse recyclables before putting them into the recycling bin. This is where their recycling codes come into play. On many different plastics and recyclable items, there will be a recycling symbol on the back, bottom, or one of the sides. Inside of this symbol will be a number. This number corresponds to the type of chemicals that were used to create this plastic. Some chemicals are toxic and not healthy to use for human consumption after its first use, and others can be safely used more than once. Some ways you can reuse plastics is by finding new ways they can be useful. For example, you can take a plastic liter bottle, cut it in half, and use the plastic as a planter. If you have young kids, there are plenty of cool arts and crafts ideas you can do, that uses left over plastic containers. The possibilities are endless! And you have created something new out of something that would have just been throw away.

Another way you can help protect our wetlands and keep them clean is by getting involved. Volunteer for cleanups around your city or beaches, contact state environmental agencies, like DNREC, to see how you can help. If you live near a shoreline, consider having a living shoreline. You can use non-toxic, unbleached, and phosphate free cleaning supplies, detergents, and lawn care products to prevent toxic chemicals from entering into our waterways and wetlands. Or if you see something, say something. If you see someone liter, say something to them and educate them on why they shouldn’t liter. With these steps in mind, you can become a wetland steward and feel good about the positive impact you are having on the cleanliness and health of Delaware’s wetlands!

For more information on recycling, please visit DNREC’s “How to Recycle Guide” and other useful information.