Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: December 19th, 2015 in Education and Outreach

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Coastal Plain Seasonal Ponds, also called Delmarva Bays, are small, shallow, seasonally-wet areas. They are fed by groundwater, rain or snow and usually fill up in winter and spring and dry out in summer and fall. Often surrounded by woodlands, the inner (wetter) zones feature a variety of low shrubs (e.g. buttonbush and blueberry) and grassy plants.

Coastal Plain Seasonal Ponds are gems across the Delmarva landscape because of their unique geologic formation, water level fluctuations, and special plant and animal communities. Although regionally these special wetlands occur from Massachusetts to Florida, they are rare in Delaware and make up only about 2% of the state’s total wetland acreage. Delaware has several hundred small Coastal Plain Seasonal Ponds which are concentrated in inland parts of lower New Castle and upper/middle Kent counties (Blackbird area).

Coastal Plain Seasonal Ponds provide critical habitat to many state and globally rare or threatened animals (such as the marbled salamander and carpenter frog) and plants (such as Hirst Brothers’ panic grass and featherfoil). They support 50 plant species considered rare or uncommon in the state, and nine plant species which are classified as rare in the world. These wetlands are especially vital to amphibians for breeding and survival. Frogs and salamanders use the temporary ponds to find mates and lay egg clusters – and can only do so because predatory fish cannot survive in the temporary ponded water. In the summer they use the surrounding drier forested wetlands and uplands as summer habitat, hiding under moist fallen leaves and logs to stay cool.

Many of these habitats have been already lost, and those remaining are vulnerable to degradation or loss. Coastal Plain Seasonal Ponds are not connected to streams or other waterways and are isolated on the landscape. This detail prevents them from being regulated by either the federal or state government and makes them more vulnerable to harmful wetland impacts such as filling or draining. Preservation of these wetlands, and of adjacent contiguous forested habitat, is a high conservation priority. Voluntary conservation and vegetated buffers are prime ways to care for these unique features. For more information contact Mark.Biddle@delaware.gov or call 302-739-9939.

Written on: November 25th, 2015 in Wetland Research

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Groundwater and Delaware’s Wetlands

Approximately 71 percent of the Earth’s surface is covered in water, and it makes an incredible journey around the globe. Water can travel up into the atmosphere and back down into the land; moving from plants, to clouds, to soils, and can even make its way underground. Water that is stored under the soil is called groundwater, and clean, drinkable groundwater is a highly sought after natural resource.

But how can groundwater be cleaned you ask? Before water travels to underground storage units (aquifers), it can first go through, and be filtered in our wetlands. As water moves down through wetland soils, nutrients, such as phosphorus and nitrogen, and sediments are filtered out, purifying the water.

Just one acre of wetlands can store as much as 300,000 gallons of water, but water levels vary greatly depending on the season. During the wetter months of winter and spring water can be seen on the surface, while during the dryer months of summer and fall you may not find water in wetlands until you start digging. To track these changes, we will establish a long-term dataset that monitors groundwater levels in Delaware’s wetlands.

But how do you measure how much water is in a wetland? Why, through the installation of wells of course. In late October of 2015, we installed a series of shallow water monitoring wells that began collecting data as part of a long term project to understand what is happening to groundwater levels in Delaware’s headwater flat and floodplain riverine wetlands. The data gathered from these well monitoring sites will help us place a value on some of the services wetlands provide, and better understand the ability of Delaware’s wetlands to store water, reduce flooding and create cleaner waters.

Well Installation

Three sites were chosen at each of the Ted Harvey Conservation Area’s flat wetlands and the Blackbird State Forest’s riverine wetlands. The well installation process began in the dry months of the fall when groundwater levels were at their lowest. This ensured that water would be present in the wells throughout the entire year. A straight 4 inch diameter hole was dug using an auger to a predetermined depth, 8 feet deep for the Ted Harvey Conservation Area, and 5 feet deep for the Blackbird State Forest.

After the hole was dug, a PVC pipe with tiny grooves cut into it to allow water to pass through was inserted, and then sand was filled in around the pipe to lock it in place. The tricky part was to make sure that the pipe was completely horizontal and at the correct depth.

After the pipe was secured, it was topped off with a clay bentonite mixture that sealed the PVC to the opening in the ground preventing rainwater from entering the well and skewing water level results. To measure and track the groundwater levels, waterproof dataloggers that automatically record temperature and pressure were installed underground at the bottom of each of the PVC pipes, and a reference one was installed above ground at each site.

We will come back to these wells periodically throughout the year to download the data, make sure everything is functioning properly, and if all goes “well,” gain some interesting insights to share.

Check out this short video of the well install process at the Blackbird State Forest.

Written on: October 23rd, 2015 in Living Shorelines

A “Living Shoreline” is a method of bank stabilization that reinforces the shoreline to protect coastal properties from erosion, while also restoring and enhancing fish, wildlife water quality and wetland habitat. Unlike bulkheads and stone riprap, living shorelines use natural materials to maintain existing connections between the shoreline and aquatic areas. A number of living shoreline materials and tactics are available, including coconut fiber coir logs, natural fiber matting, recycled shell, and native wetland vegetation.

Living shorelines have been built throughout Delaware’s coastal regions and are a popular option for bank stabilization because they protect property from erosion while attracting fish and shellfish, filtering polluted runoff, and absorbing wave energy during storms.

This restoration site was constructed to address an undercut and deteriorating existing salt marsh shoreline. The site is exposed to low energy for the majority of the time with peaks of energy from boats launching from the opposite shoreline. The site has low energy, so standard vegetated living shoreline tactics were selected. Shorelines subject to high wave energy may require marsh sills or offshore breakwaters but should only be used when necessary.

The slope of the eroding shoreline required two tiers of coconut fiber logs staked on top of each other to reach the optimal elevation for Spartina grass. The first round of coconut fiber matting and logs were positioned in the intertidal zone before being staked down and tied in place. Oyster shell bags were then arranged in front of the coir logs to further armor the shoreline and absorb wave energy. The next step was to allow sediment to fall out of the naturally turbid water into the cells created by the coconut fiber logs.

This Living Shoreline project was installed on April 14-17, 2014. After 6 months enough sediment had built up inside the shoreline that the second tier of coconut fiber logs were installed on October 20, 2014. The second tier of logs allowed sediment to continue to accumulate and raise the elevation to the optimal growing elevation for Smooth Cordgrass. The site was planted in March/April 2015 with Smooth Cordgrass. Spring planting allowed vegetation to take root throughout the growing season before winter storms.

Living Shorelines may need augmentation over the years. However, successful projects throughout the Mid-Atlantic have survived multiple hurricanes!

This project was collaboration between Delaware Department of Natural Resources, Partnership for the Delaware Estuary and Delaware Center for the Inland Bays.

Written on: October 23rd, 2015 in Living Shorelines

A “Living Shoreline” is a method of bank stabilization that reinforces the shoreline to protect coastal properties from erosion, while also restoring and enhancing fish and wildlife habitat. Unlike bulkheads and revetments, living shorelines use natural materials to maintain existing connections between the shoreline and aquatic areas. A number of living shoreline materials and tactics are available, including coconut fiber logs, recycled shell, and native wetland vegetation. Living shorelines have been built throughout coastal regions and are a popular option for bank stabilization because they protect property from erosion while attracting fish and shellfish, filtering stormwater, and absorbing wave energy during storms.

Two uniquely different shorelines were restored at the Indian River Marina in Rehoboth Beach, DE. The “marsh” restoration site was constructed to address an undercut and deteriorating existing salt marsh shoreline. The “rip rap” restoration site was built along a sandy shoreline as an option for “greening-up” an existing rip rap structure. Both sites are exposed to low wave energy, so standard vegetated living shoreline tactics were selected. Shorelines subject to high wave energy may require marsh sills or offshore breakwaters but should only be used when necessary.

Coconut fiber matting and logs were positioned in the intertidal zone before being staked down tied in place. Oyster shell bags were then arranged in front of the coir logs to further armor the shoreline and absorb wave energy. Following installation, clean sand fill was brought to the restoration sites and graded to the desired elevation and slope before planting with Smooth Cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora).

Both living shoreline projects were installed on April 14-17, 2014. While many shorelines will naturally collect sediment, after 2 months of monitoring this area approximately 45 yd3 of clean sand was used to grade the shorelines to the optimal growing elevation for Smooth Cordgrass. Sites were be planted in March 2015 with Smooth Cordgrass. Spring planting allows vegetation to take root throughout the growing season before winter storms.

Living shorelines may need slight augmentation over the years. However, successful projects throughout the Mid-Atlantic have survived multiple hurricanes!

This project was collaboration between Delaware Department of Natural Resources, Partnership for the Delaware Estuary and Delaware Center for the Inland Bays.

Written on: October 23rd, 2015 in Living Shorelines

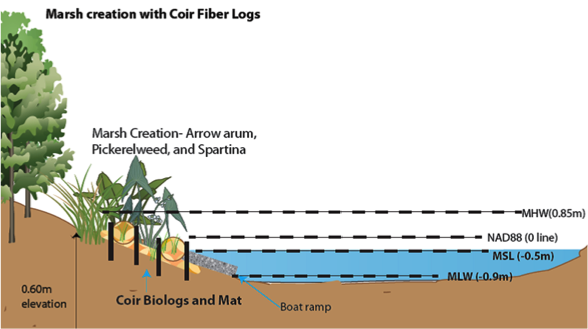

A “living shoreline” is a technique used to either protect or restore a shoreline, and is built using natural materials and native plants to mimic native coastal habitats. Natural materials used in living shorelines include: sand, coconut-fiber logs coir logs and mats, oyster shell bags, live mussels and plants. Living shorelines protect the shoreline from erosion and defend our coasts from damaging storm wave energy, all the while encouraging native plants and wildlife.

In the case of the Blackbird Creek Reserve living shoreline sites, the shoreline on either side of the kayak ramp was shifting and washing away due, in part, to quick moving river currents (Figure 2.). To prevent further erosion, or loss, of the shoreline and to protect the adjacent habitat, two living shorelines were installed in early May of 2015.

This project began by placing a series of coir logs, sand, dirt and wooden stakes along the bank to increase the height of the bank above the water level. These logs were placed on mats to stop them from sinking in the mud, and then staked in to keep them from moving. Coir logs act as temporary fences to hold soil in place and also trap sediments floating in the water column, giving plants a great habitat to grow. The West side location already had a native wetland plant, arrow arum, growing, but the east side location on the other side of the ramp was empty so clean sand was trucked in and topped with a little soil to create a nice high base (Figure 3.).

Once the mats, logs and sand were in place, a few weeks passed by to allow things to settle. In June of 2015, a variety of native plants (arrow arum, smooth cordgrass, pickerelweed, saltmarsh bulrush, yellow sneezeweed, swamp rose, marsh hibiscus, New York ironweed and pin oak) were planted in the projects. Once these plants start to grow, they will help further trap sediments, stabilize the bank and completely cover the coir log structures.

The site is regularly monitored to track progress, and is a collaboration between Delaware’s Natural Resources and Environmental Controls (DNREC) Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program (WMAP), the Delaware National Estuarine Reserve (DNERR) and the Division of Fish and Wildlife.

Written on: July 15th, 2015 in Education and Outreach

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

The Wetland Warrior Award is presented annually by our program to an individual or organization that has acted to benefit Delaware’s wetlands through outreach and education, monitoring, restoration or protection. This year we would like to recognize two recipients that have dedicated significant amounts of time and energy to protecting Delaware’s wetlands.

Douglas Janiec has been a professional working in Delaware’s wetlands since 1989, and is highly regarded for his work in performing wetland ecological risk assessments, effectively resolving wetland violations, and developing innovative stream and wetland restoration practices. Not only does he support Delaware’s wetlands while on the job, but he has also volunteered countless hours of his personal time.

Thomas Draper and his family are voluntary stewards over one of Delaware’s most ecologically valuable wetlands, Coastal Plain Ponds or Delmarva Bays, which are one of seven unique wetland community types in Delaware. Tom and his son Hank are prime examples of landowners that are able to balance their agricultural production while actively maintaining and managing unique wetlands. Their efforts are shown by the rare plant and animal species that are thriving on their properties.

Douglas Janiec and the Draper family were recognized by Governor Markell and DNREC Secretary David Small on Governor’s Day, Thursday, July 30th, at the State Fair for their valiant efforts. We thank you for dedicating substantial and sustained energy, wisdom, and leadership in protecting Delaware’s wetland resources.

Written on: July 15th, 2015 in Wetland Restoration

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

In June of this year, one of the largest marsh restoration projects on the east coast began at the Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge located in Milton, Delaware. This $38 million project, which focuses on building storm and sea level rise resiliency back into the natural landscape and creating habitat for birds, will repair breached marshes and reconstruct damaged shorelines to 4,000 acres of tidal marsh.

The first phase of the project involved dredging out the historic tidal channels to restore natural wetland hydrology and reusing the dredged material to increase elevation of the Prime Hook marshes. Higher marsh elevation combined with lower water levels will effectively create suitable habitat for marsh plants and animals to re-colonize and thrive.

There are many partners involved in this ground-breaking project, and we were lucky enough to be one of them. Our program, in conjunction with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, was responsible for monitoring the Prime Hook marshes before the restoration began. The sampling efforts documented the elevation, types of plants present, plant percent cover and biomass, and stability of the ground at preselected points across the marsh. In the future, this information will be used as baseline data, or a starting point, to track changes in the marsh community.

The second phase of the project is scheduled to begin in October and will fill holes created from hurricanes and storms in over a mile of dunes. The dunes will then be planted with beach grasses and shrubs to hold the sand in place.

For more information and updates about this project please visit the Prime Hook National Wildlife Refuge website.

Written on: July 15th, 2015 in Education and Outreach

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Delaware is host to roughly 320,000 acres of wetlands that vary in salinity, soil type and vegetation. Since the early 1700’s, Delaware has lost 1/2 of its wetlands and they continue to be lost or degraded at an alarming rate.

There is a healthy network of groups around the state dedicated to studying, protecting and improving wetlands for future generations of Delaware residents and visitors. This network includes state, county, federal, private, non-profit and academic groups.

The new 2015 Delaware Wetlands Management Plan identifies and prioritizes areas where information or collaborative action is needed to protect Delaware’s wetlands. Based on the advice of the network, seven goals to develop an effective and efficient wetland program have been identified.

As steps are made towards achieving these goals, Delaware will have grown new and more efficient capabilities, strengthened partnerships, reached new audiences and made overall progress towards protecting, enhancing and restoring wetlands. Click here for the complete report.