Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube RSS Feed

Written on: March 5th, 2020 in Living Shorelines, Outreach, Wetland Restorations

by Erin Dorset, DNREC Wetlands Monitoring & Assessment Program

If you’re in the world of wetlands, sea level rise is a common topic of conversation. For example, here on our blog, we’ve talked about long-term monitoring efforts relating to marsh resilience in the face of rising seas and about saltwater intrusion into forested freshwater wetlands. We’ve also had a contributing author discuss effects of rising seas on trees near tidal marshes. However, sometimes we forget to stop and think about the reasons why we are experiencing sea level rise. So, let’s back up a little bit.

Sea level rise largely began with global warming, or an increase in Earth’s global temperatures. Global warming is caused by greenhouse gases absorbing and trapping solar radiation, which warms the planet more rapidly than would occur naturally. As global temperatures have risen, massive ice sheets and glaciers in Greenland and Antarctica have begun to melt rapidly, increasing sea levels. Plus, as ocean waters get warmer, they expand, further raising water levels on a global scale.

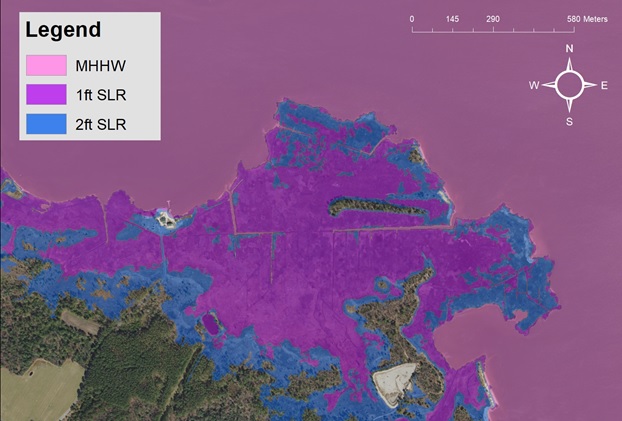

Although it is happening around the world, there are some spots that are being affected more than others. The Mid-Atlantic Coast—including Delaware—is experiencing one of the highest rates of sea level rise in the U.S, second only to the Gulf Coast.

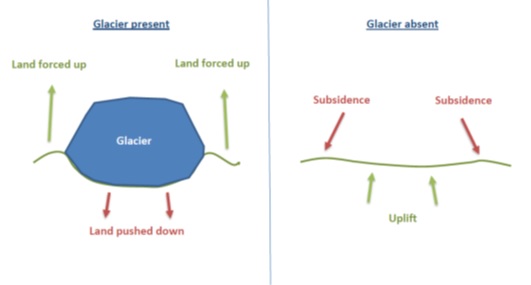

Thousands of years ago, when glaciers covered much of North America, land that was just outside of the glacial footprint—such as the Mid-Atlantic region—was forced upward as the glaciers pressed down on the land they resided upon. Once the glaciers were gone, pressure was lifted, and the land that had been forced up began to slowly sink down again. That process, called glacial isostatic adjustment, is still happening in the Mid-Atlantic today. As the land sinks, or subsides, sea levels rise even more.

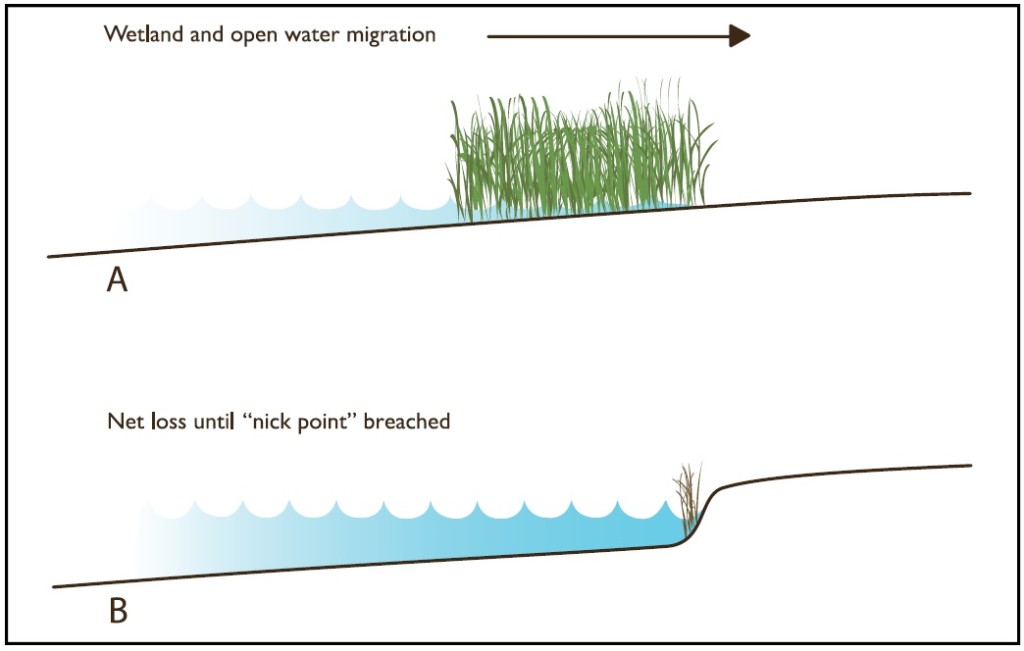

Tidal wetlands have the amazing ability to gain elevation (or height) in nature. When marsh plants die, they pile up on the marsh surface and decompose slowly, while live plants help trap and keep sediments in place and out of the water. Unfortunately, sea levels are rising too quickly in the Mid-Atlantic for many wetlands to keep up. This can result in a couple of different scenarios:

As bleak as this outlook may sound, there is hope, too. As previously mentioned, some Mid-Atlantic wetlands might be able to keep up with sea level rise by naturally gaining enough height or elevation, while others may be able to migrate inland. In places where that is not the case, scientists and land managers are looking into other ways to save or restore tidal wetlands wherever possible and make them more hardy in the face of sea level rise. A couple of these projects include:

This strategy involves using dredge material to increase elevation of struggling tidal marshes to an elevation that is optimal for plant growth, which makes them more stable. Beneficial use can also be used to rebuild marshes that have been lost completely from erosion and sea level rise. See a Delaware example!

Tidal shorelines that are suffering from erosion can become stronger by using nature-based materials, such as coir logs, coir matting, and oyster shells. Look at one of the latest Delaware examples!

By incorporating the latest sea level rise projections for the Mid-Atlantic into these kinds of projects, professionals can help put our best foot forward to help coastal wetlands in our region.