Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: December 14th, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Living Shorelines

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Hot off the press this month from the Delaware Living Shorelines Committee is a guidance document that aims to help landowners and professionals design and install nature-based shoreline stabilization projects. The Techniques and Application of Living Shorelines in Delaware guidance is the newest resource released by the Delaware committee, whose primary goal is to increase the frequency and success of living shorelines across the state.

The Techniques and Application guidance presents a compilation of common design configurations, and an overview of commonly used materials to help users conceptualize an appropriate and successful living shoreline. This guidance is the closest thing to a living shoreline cookbook as it can be. Due to an infinitely diverse set of conditions and factors in every shoreline situation, it is important to make each project a custom design that isn’t cookie cutter.

The first chapter encourages the user to define their project classification and select their project-specific goals before any design work is done; a conventional or hybrid classification? and then shoreline position, habitat, or water quality goals? The proper three-step process starts by defining project class and goals, followed by selecting design elements to meet those goals, finished by selecting materials to build those design elements.

Chapter two runs through eight significant shoreline stabilization design concepts where a living component is always present. This is where broad decisions can be made to order based on conditions and goals. These descriptions are super helpful by breaking information down as common uses, common materials used in that design element, how that element can help or hinder goals, what ecological opportunities the element provides (e.g. for oysters, SAV, sediment deposition, wildlife passage), and important limitations and considerations (navigational hazards, energy deflection, short lifespan, wildlife impingement).

The third chapter is a breakdown of seven common materials used in living shorelines. Each section includes a nice description of the material, how they are installed, their typical lifespan, and how they can expect to support life as the project settles in. Especially nice are the color-coded tables indicating which specific project goal that material can contribute to. For example, in the table below, rock material can be effective in reducing wave energy and provides a durable way to change vertical and horizontal shoreline position but has limitations with drainage (related to fish and sediment passage) and is not ideal for providing valuable habitat.

Lastly, for a little more help with visualization, is a chapter dedicated to showcasing case study examples of various designs and techniques installed around Delaware. Each of the seven examples highlights varying energy levels, design elements and materials. Each simple project-specific flyer runs through overall details, describes starting conditions, mentions the permits used, and lists out the design elements and materials that were incorporated. Lots of project photos show the reader before and after.

After completing these steps, a user should have a solid and reasonable idea to draft into drawings that can be included with permit applications and cost estimates. By thoughtfully selecting the components and materials, users are less likely to be surprised by unexpected setbacks and are more likely to reach their intended project goals.

From its inception, the Standards of Practice Sub-committee envisioned this guidance to be the next resource to fit into the suite of tools drafted by the Delaware Living Shorelines Committee that helps users through the entire process of embracing green designs to address shoreline protection and restoration needs. Other crafted resources cover topics such as site evaluation and feasibility to decide if and where a living shoreline would be appropriate, and goal-based monitoring to track success after construction.

Want to learn more about living shorelines and stay in touch with new developments? Sign up to for an upcoming webinar or catch up on past webinar recordings. Especially for professionals working in Delaware, stay tuned for details in the new year about the annual Introduction to Living Shorelines Training Workshop. Professionals interested in joining the Delaware Living Shorelines Committee should contact Committee Chair, Alison Rogerson alison.rogerson@delaware.gov. Landowners just getting started can find a provider to help them and shop for materials nearby.

Written on: December 14th, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Natural Resources, Wetland Restoration

By Phil Miller, DNREC’s Division of Watershed Stewardship

Throughout the world, the importance of Agriculture is no secret, and here in Delaware, that’s no different. If you’ve ever taken a drive through the countryside of Kent or Sussex County, you’ll pass through miles of farms producing crops, poultry, and other agricultural products for use by local communities and nearby major cities. Because of Delaware’s centralized location, producers can reach one-third of the U.S. population, within an eight-hour drive, earning the title of a “foodshed.” Foodsheds are specific geographic locations that provide food for a population, and Delaware is a perfect example.

With almost 40% of land in Delaware devoted to agriculture, making it the primary land use, you might picture much of it being owned by large companies. In fact, according to the Department of Agriculture, “about ninety percent of farms are either sole or family proprietorships or family-owned corporations.” Many of these operations are owned by families who have managed this land for generations and understand the connection between the land, waterways, wildlife, and the overall quality of Delawarean’s lives.

Understanding the importance of this connection is key to maintaining a natural balance between healthy watersheds and agricultural practices. While farms play a very crucial role in the survival of much of the U.S. population, they can also be a nonpoint source (NPS) of pollution. NPS pollution, different from point source pollution such as industrial and sewage treatment plants, comes from runoff caused by rainfall or snowmelt, moving over or under the ground. Unmanaged runoff from farms is one of the leading nonpoint sources of pollution. This can be from sedimentation where soil is washed off fields and carried to nearby streams and lakes, or excess nutrients finding its way to local waterways in the form of chemical fertilizers, manure, and sludge.

Nutrient and sediment pollution are two leading factors of impairments to Delaware’s waterways. Well- informed farmers know the importance of installing practices that will improve the health of their watersheds, which in return can provide better products. Certain conservation practices are essential for improving local water quality, which not only benefits the farm, but also the economy, local wildlife, human health, and recreational activities like fishing and swimming. Agricultural producers with cropland or marginal pastureland in Delaware, may work with State and Federal partners to reserve portions of this land in production for conservation, and receive payments through the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP).

Through CREP, conservation practices are installed that are designed to reduce nutrient and sediment loadings in impaired streams. They also improve water temperature and levels of dissolved oxygen, which are necessary to support biology and wildlife. Eligible practices include projects such as restoring wetlands and creating shallow water areas for wildlife. Hardwood tree plantings, creating permanent wildlife habitat, planting riparian forested buffers, and installing filter strips are also eligible for CREP.

Among other benefits, restoring wetlands and similar practices allow for water to soak naturally into the ground acting as a filter, rather than creating runoff. Programs like CREP are essential for maintaining the balance between agriculture and healthy sustainable watersheds. To learn more about CREP or to see if your land is eligible, please visit the DNREC webpage here.

Written on: December 14th, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Research

By Alison Stouffer, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

While you may be sweating out in the field, you shouldn’t be sweating your appearance. With just a few staple pieces, you can dress to impress on the environmental runway. This guide will provide you with the basics of field fashion so you can turn heads (ignore the confused looks and raised eyebrows) and tackle your work in style.

General Attire

Regardless of the season, dressing for the field is easy. Simply open that drawer in the depths of your closet where you keep your old cotton t-shirts and long sleeves from high school and pull out your favorite one! Now, if you’re like me, these shirts likely have a fair number of small holes dotting them. I like to think of these imperfections as the key to the perfect field fit. Every hole is an opportunity to release the pungent smell of hard work that comes with conducting fieldwork. Of course, a shirt alone doesn’t always provide the necessary protections against the elements. Additional layers in the form of sun sleeves (a unanimous favorite of my colleagues), sun shirts, button-up collared shirts, sweatshirts, rain ponchos, and even ski jackets can be incorporated as needed to really complete the look.

Once you’ve got your top down, it’s time to move to the bottoms. Like any other runway, you might want to try to match your pants and shirt for a cohesive look. I would suggest sticking with variations of tan, black, or gray. Not only will these compliment your cherished high school shirt, but they are also likely the only colors you have to choose from when it comes to quick-dry pants. For some added flair, consider convertible pants that can be zipped off into shorts and/or pants with lots of pockets (imagine all the snack storage). These add both style and functionality to your field fashion.

On special occasions, you might have to pull out all the stops. I’m talking about wetsuits and waders – the power suits of the environmental field. Just remember, whether you are rocking a t-shirt and pants or a wetsuit and waders, every layer is a barrier to rapid dis-robbing in the event of an emergency bathroom break!

Footwear

The second most important component of your funky field fit is footwear. While a tasteful loafer or bold chunky heel might please the fans of a traditional runway, we are big supporters of the classic boot. At first glance, a boot might seem rather basic. However, here on the environmental runway, boots can be of the hiking, ankle, knee, or hip variety. What they lack in proper fit, breathability, arch support, and comfort, they make up for in waterproofness – that is, of course, until you inevitably top them, and they fill with water. Or, even better, you poke a hole in them and they start to leak. Even so, their versatility really makes them perfect for every occasion. Just remember, these boots weren’t made for walking so appreciate boat travel when you can or have a stash of blister pads on hand and at the ready.

For those trendsetters out there, other footwear options include barefoot, sandals, old sneakers, neoprene booties, and even bread bags. Some of these options prove more practical than others and tend to be situationally specific. For example, bare feet are highly discouraged unless walking around the office or crawling out of a mudflat after losing your boot to said mudflat. Alternatively, bread bags and neoprene booties provide additional waterproofing and insulation to existing footwear.

Accessories

With the main components of your field fit finalized, it’s time to accessorize. This is a make-or-break point for the environmental runway. Accessories are the single most important way to show off your unique style and outdo your colleagues in field preparedness.

The best place to begin is with proper head gear (and I’m not talking about the contraption your orthodontist might have made you suffer through as a child). For many, prime field fashion season is in the hot months of the summer where a brimmed hat might be the only source of shade as far as the eye can see. I personally oscillate between a floppy bucket hat and the classic baseball cap, with others preferring to go the visor route. The dingier and more sun-faded the better. In the colder seasons, these hats can be replaced with beanies (ear flaps optional). Feel free to really bring out your personality here and show the world your favorite sports teams, where you went to school, what restaurants you frequent, your place of work, etc.

Other accessories include neck gaiters, polarized sunglasses, sunglass straps, watches, backpacks, and personal protective equipment (PPE). Many of these accessories perfect the balance between style and function. Neck gaiters, for example, are an attractive way to wipe the beads of sweat trickling down your face, prevent mosquito bites, or hide your sniffer from the ever-present musk of rotten eggs and body odor. Similarly, PPE protects your most valuable physical features while adding a bold pop of color – safety orange and yellow are always crowd favorites – to your field fit. While you will absolutely slay the environmental runway in whatever accessories you choose, it is imperative that you remember field fashion is a harsh industry. Sunglasses will disappear, watches will short circuit, backpacks will rip, and some component of your field fit will likely be lost to nature – never to be seen again.

While many accessories discussed here are up to your discretion, one accessory that is obligatory – no exceptions! – s the creative placement of mud and dirt. The environmental runway is a slippery, unsteady, and challenging place to walk. You will fall down, and you will get muddy. How much mud, the location of the mud, and the natural design it creates will win you significant bonus points (and not to mention street cred) for your field fit.

The environmental runway is a low-stakes way to flaunt your field fit while staying prepared for all that fieldwork throws at you. With this guidance in mind, I have no doubt you will be able to balance style and functionality. Now get out there, put in the work, and don’t be afraid to put your most fashionable foot forward!

Written on: September 22nd, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Natural Resources

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

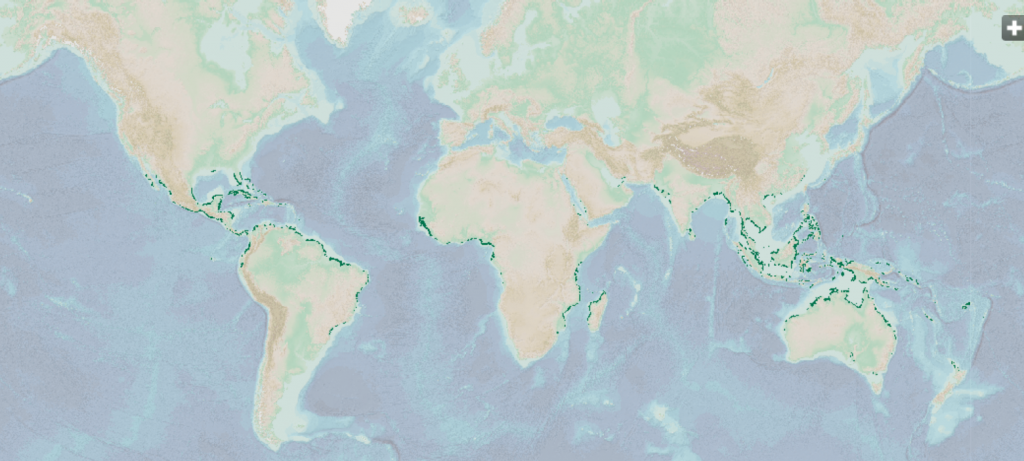

Magical forest, walking trees, mangals, snorkeling roots – this habitat can be called by many names. With a worldwide distribution in tropical to warm temperature latitudes, mangrove forests are not only incredible ecosystems, but a key player in climate resiliency and human livelihood. If you’ve been to the lower half of the United States, specifically southern Florida and the Gulf Coast of Texas, you may have come across this type of coastal wetland. If you’re more of a world traveler, it’s likely you may encounter a mangrove along your journey, as these wetlands reside on five out of seven continents on the globe.

Let’s get to know mangrove forests from root to tip. These coastal wetlands consist of groups of shrubs and trees that are uniquely adapted to estuarine tidal and marine conditions. Living in these ecosystems means that mangroves must be able to survive not only in waterlogged soils with oxygen-poor sediment, but also in saltwater experiencing daily tidal cycles. In order to grow in such harsh conditions, the roots are often sprawled above the water and below in sediment – a bit different than most plants. Along with the unique structure of their roots, mangroves can also filter out the salt from water as it enters their roots by secreting salt out of special glands on the leaves. This dynamic duo of adaptations allows the flowering part of the plant (the branches and leaves) to live above the water line, while the above and below ground root system maintains stability under the water.

When it comes to overcoming growth challenges, mangroves have really thought this one through. Regular coastal flooding can make most plants reproduction a more than difficult task. However, mangroves have adapted to use the tides and proximity to waves to their advantage through vivipary. This simply means that the offspring begin to grow while still attached to their parent plant, and in this case, far above the salt water. After pollination and germination, the seedlings fall into the water to then be swept away by the tides and wave action nearby. Next stop, the bottom of a muddy tidal wetland to grow out of the water and hopefully play a role in another mangrove colony.

According to The Nature Conservancy, there are approximately 70 species of trees and shrubs that make up mangrove plants communities of the world. Chilly or freezing waters are a big no no for mangroves, so it’s not a surprise that their distribution is only in tropical and subtropical latitudes near the equator. The various species across the globe are not necessarily closely related but do all share the distinct capability of growing dense roots out of the water in salty and often unstable conditions. For us here in continental United States, only three species of mangrove grow: black, red, and white mangroves.

Now, we’ve discussed the benefits and necessity for coastal wetlands on our blog before. But in standard fashion, each wetland habitat comes with its own intricate set of ecological and societal benefits. The fact that mangroves thrive in such harsh conditions is already remarkable; below are even more reasons to give them credit.

Habitat and Biodiversity

A mangroves maze of woody roots creates an intricate network of available habitat for numerous plants and animals. They are dense aquatic forests, a few miles in size, that provide areas for migratory birds, exotic fish and reptiles, heathy trees, and even furry friends like lemurs and panthers. As a nursery habitat, many small fish and invertebrates such as crabs and shrimp grow safely in mangroves and later move on to open water areas such as coral reefs. Recent data from The Nature Conservancy shows that mangroves are home to 341 internationally threatened species. And if you haven’t recognized their wonder yet, just Google a sloth swimming in a mangrove to really see the “wow factor”.

Blue Carbon Sequesters

Like all trees, especially in wetlands, mangroves absorb and store carbon from the atmosphere. What sets these habitats apart from the rest is how they store it. Once leaves and older trees die in a mangrove forest, they fall into the water and take the stored carbon with them to be buried in the soil. This is what we call “blue carbon” because it is stored underwater in the coastal ecosystem. Storing substantial amounts of carbon has proven to offset carbon emissions that drive the current climate crisis. The Smithsonian Ocean predicts one acre of mangrove forest can store about 1,450 pounds of carbon per year – roughly the same amount emitted by a car driving straight across the United States and back. Another reason to love mangroves and wetlands; they keep our air cleaner.

Coastline Protectors

This is a big one. Mangroves protect our shorelines and coastal areas more than we can imagine. As natural infrastructure, they provide protection to populated coastal areas by reducing flood impacts and property damages during extreme weather events. Mangrove forests buffer wave and wind energy as a first line of defense during strong storms. Also, their dense, aboveground roots slow down water flow and hold deposited sediment in place mitigating impacts from sea level rise. Last, their complex, underground root systems help cycle and filter excess nutrients reducing pollution and improving water quality.

Recreation and Culture

It’s a universal truth; the outdoors can bring people joy. Kayaking, snorkeling, fishing, birding, the list goes on. Mangroves can provide an invaluable natural experience because of their biodiversity and geographic location in some of the most tropical places on Earth. In addition to the everyday recreation, the traditional use of mangrove habitats dates to the BC times. These highly sustainable practices for hunting, timber, and food production are still in use today in some South American and African countries but may be lost with ecosystem degradation. The livelihoods of coastal cultures worldwide have become intertwined with mangrove forests whether it be through living spaces to nature clubs, small scale businesses to historic heritage sites.

Like many coastal ecosystems, these habitats unfortunately face a variety of threats and are being lost at a rapid rate. Whether experiencing habitat destruction from human impact like aquaculture or development, threats from sea level rise, damages from coastal storms and flooding – mangroves are up against some tough odds. The hard times of the modern age have brought on bigger and better ideas in conservation for mangroves, but all the answers are not clear yet. Science and education, reforestation projects, monitoring, policy adaptation – these are some of the ingredients to the recipe for success. But if there is a future for mangrove forests in our world, it may be useful to look at them as part of the solution. After all, they are masters at adaptation and overcoming intense challenges daily. From The Sundarbans of India and Bangladesh to the Galapagos Islands and The Everglades in southern Florida, mangroves are wetland wonderlands like no other.

Written on: September 22nd, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Natural Resources

By Beatrice Arce, MANO Project Fellow with the Hispanic Access Foundation

A year ago, I became an environmental professional after completing my educational journey in biology and environmental science. I am a first-generation college graduate, product of two tenacious Hispanic parents, my mother in administration at an environmental consulting firm and my father a salesman of fine oriental rugs in Houston, Texas. A mixture of an interest in my mother’s profession and love for science piqued my interest in this career; although, I did not know what I was getting myself into. Not in a bad way, though.

Stepping into the world of environmental consulting has become a transformative journey. For those who dedicate themselves to this profession, nature takes on a whole new meaning. After a year immersed in the field, my perspective on the natural world has shifted, affording me a new appreciation for its complexities and greater understanding towards its preservation. I am so very gracious to call my profession my own. Can you imagine being outdoors for work a quarter of the time?!

The Heck Are These Humans Doing to Nature?

First things first: what is an environmental consultant?! A majority of what my role consists of is measuring human interaction with the environment. Going into college, I was a bright-eyed student looking to positively contribute to conservation principles. But I’m not going to lie, I didn’t think it would be through the measure of human impact on the environment. Honestly, I had no idea what it would consist of. I just liked trees. When I enter a job site, I am more often than not identifying the altered and unnatural than nature itself. The projects I complete generally fall into three categories: prevention, reporting, and assessment. Our clients often request services mandated by state and/or federal regulations. However, I hope my work not only helps them meets these requirements but also sparks a deeper sense of environmental responsibility within their organization.

Consultants witness the consequences of industrial processes (e.g. oil spills), urban development (e.g. construction), and resource extraction (e.g. natural gas extraction). Yet, they also witness the potential for responsible, sustainable practices that harmonize with nature rather than exploit it (e.g. pollution prevention plans, Tier II reporting).

Let me list some projects I have gained experience from this position:

College gave me a great foundation to build knowledge on as an environmental consultant. But nothing prepares you for what you will learn in the field until you simply go through the motions. At the beginning of my consulting career, nature seemed untamed and overwhelming. I have now grown to recognize patterns within the noise and rhythms in specific industries.

What Growth Looks Like in Consulting

As a first gen, I definitely took a lot of guesses on how to land into a position like my own. Advancement was no longer linear as it once was. Although, I challenge you to see this chaos as a privilege rather than a setback! The non-linear configuration of a professional career allows specificity in particular interests you have. I have found myself to be forming into nonprofit leadership, which is a position I would have dreamt of five years ago! You’ll be surprised how quickly you adapt to situations and positions that were made for you. Kind of like nature.

It’s easy to become disheartened by the audacities you witness being done to the environment as a consultant. Although, with these gained experiences you also will begin to recognize nature’s remarkable ability to adapt and the environmental protections that are in place to mitigate damage. Ecosystems rebound from disturbances and state and federal agencies have regulations in place to safeguard natural resources. I have so much hope for the advancement in environmental stewardship!

Finding My Role

A wonderful past professor of mine by the name of Dr. Sam Atkinson asked me on the day I defended my M.S. degree, “So, what do you want to be when you grow up?”. And to that, I say, “The best I can be.”.

A beauty about science is constant learning. I hope one day to reach the level of a wise, intuitive consultant that uses their knowledge to inform local communities through grassroot initiatives (on top of my position, of course!). I believe environmental consultants hold a unique position to serve as an instrument of sustainable development and knowledge. I hope to meander to a specific passion in my journey. Find my niche in an ecosystem, if you will.

Written on: September 22nd, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Natural Resources

By Alondra Ureña, MANO Project Fellow with the Hispanic Access Foundation

The last few months have brought me a myriad of new experiences as an Endangered Species intern at the Sacramento Fish & Wildlife Office, from getting started on my internship deliverables to visiting my first wildlife refuge (I’ve now visited 4!), to celebrating Latino Conservation Week. I’ve participated in a 3-day training on Effect Pathway Manager (EPM), for the Service’s Information for Consultation and Planning (IPaC) system, helping to streamline technical assistance to agency partners. This is a large focus of my work during my internship, and I am in the process of assessing resource needs and collecting conservation measures for vernal pool fairy shrimp. I will input data into EPM to analyze the effects of human urbanization and development in the fairy shrimp’s habitats. It’s been a joy learning about vernal pools and fairy shrimp’s unique life cycle through a literature research extravaganza; it’s even more special knowing that I get to use my research to help protect these endangered Anostraca.

In between readings and research, I’ve participated in side quests that I could have only dreamed of as a young kid, and which have elevated my internship experience. I was lucky enough to attend Latino Conservation Week 2023 at the Minnesota Valley National Wildlife Refuge. I met other Hispanic Access Foundation interns and the MANO program associate, Yashira M. Valentin Feliciano. The night before the event, I went to my first baseball game in Minneapolis for the Twins vs. White Sox, the Twins won! Yashira and I met early the day of the event to set up our table with flyers, MANO swag including Latino Conservation Week 2023 stickers and tote bags, plus a temporary tattoo station. The temporary tattoo station was a hit: everyone, from children to moms to artists, were interested in representing the beautiful Latino Conservation Week 2023 emblem. We all enjoyed live music, performances from traditional Aztec dancers, and empanadas from a local food truck. The trip was an experience I’ll never forget, especially with how meaningful it was to celebrate ten years of the event with my Latinx community and my first time in the Midwest.

I’ve also expanded my fieldwork skills. I supported Dr. Jaymme Marty in setting pitfall traps and relocating over 60 endangered California tiger salamanders at Travis Air Force Base. I’ve participated in two field visits to Antioch Dunes National Wildlife Refuge for Lange’s metalmark butterfly surveys. We observed and identified other butterfly species including the California sisters, mournful duskywing, and skippers, but sadly not Lange’s metalmark butterfly. Out on the dunes, I felt an internal surge of peace as I realized I hadn’t spent as much time outdoors like this since I was a kid playing in the park with my primos and primas every weekend. When was the last time I enjoyed the outdoors, not thinking about watching a show after work or what I’d cook for dinner, but letting myself feel the sun and get lost staring at a butterfly? It’s been very healing for my inner child and after months of staying indoors for the pandemic and working in retail, the last few weeks have been a breath of fresh air. It’s been a sign of true alignment with my purpose in conservation as well as a reminder for me to never be afraid to be an intern, start over, and rediscover myself, my passions, and mi comunidad.

Written on: July 26th, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Research

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Imagine yourself at one of these places in Delaware: up a rooted trail in the Piedmont region, down a sandy path near the coast of the Atlantic Ocean, or along a pondside trail in a mature upland forest. You snap a few photos and stop along the way to look at some wildlife, then you pop a squat next to some shiny leaves and tree with vines to chug your water with an afternoon snack. When you get home, you’re feeling refreshed, in the Zen zone with nature, and head to bed for night. The next day you awake to the feeling of an…oozy, itchy, rash? Rash?! Yep, there it is. The gleaming redness from coming into contact with poison ivy.

Many of us have been there, and a few of us have had the chance to meet some of the rarer plant species even worse than poison ivy. For this month’s blog post, we’re taking a look at the poisonous and dangerous plants that call Delaware home, many of which are found throughout the state’s wetlands. Though some are elusive others are easy to encounter, being able to identify these species can be an important step for smoothing sailing in the great outdoors.

Poison Ivy, Sumac, and Oak

Let’s start with the more notorious of the bunch, Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). This species grows plentiful pretty much anywhere – roadside, wetlands, public parks, forests, along the water’s edge, your backyard. In the early spring and fall the leaves of the plant are red or orange, and by the time summer rolls around they are a noticeable shiny green. The plant can grow as a woody vine up high or in a shrub-like fashion low on the ground, with each leaf consisting of three leaflets. All parts of poison ivy contain a dangerous skin irritant which most folks are sensitive to, and develop a reaction anywhere between 8 to 48 hours after touching it or encountering objects that have touched the plant.

Poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) and poison oak (Toxicodendron pubescens) are more uncommon to the average person but are often seen in wetlands. Sumac is a close relative to ivy and oak yet tends to more allergenic and is distinctly taller than the other two species, reaching up to 20 feet tall. This plant can be identified by its large compound leaves with 7 to 13 leaflets, red stems, and clusters of waxy berries produced in late summer. Moving on to poison oak, this species leaves resemble an oak leaf (hence the name), but it is not a member of the oak family. This plant is also a low shrub that shares poison ivy’s three-leaf clusters, except its leaves are fuzzy and lobed with rounded tips. At most the plant grows about 3 feet tall and changes color seasonally; the leaves are green in the spring, yellowish-pink in the summer, and brown in the fall.

So, what is the common denominator between all three of these species? Urushiol. This light, colorless oil is released through all parts of the plant and when it comes into contact with human skin, an allergic reaction can begin. Reactions include itchiness, red rashes, swelling, and blisters, and the sensation for some can feel relentless. Urushiol is pretty toxic stuff and can remain hidden on tools, clothes, or really anything that has come in contact with the oil. If you have crossed paths with any three of these plant species, you’d most likely know it.

Stinging Nettle and Devil’s Walking Stick

Our next species is not only seen in Delaware’s wetlands, but also is considered a common garden weed. Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) is an invasive species that can be found in dense stands with stems that pack a nasty punch. This slender, upright growing plant can be anywhere from 6 to 8 feet tall and when in bloom, has greenish-white flowers in branching clusters. The stems of the plant have tiny needle-like stinging hairs that can cause a sensation for a few minutes up to several hours if touched – like a bad bee sting. To avoid the more painful way of identifying a stinging nettle, look for its drooping flowers, hairy stems, and oval, toothed leaves.

As an exotic looking native to the United States, devil’s walking stick (Aralia spinosa) says it all in the name. Growing anywhere from 10 to 25 feet tall, these plants clubbed-shaped branches have vicious prickles that really can getcha’. Not only can the plant be recognized by its sharp spines, but also by its enormous clusters of green leaves that form in a canopy at the top of the plant. The good news about this species is that you’d only encounter the prickles during the first year of growth; as the tree matures, the stems gradually lose their spines and form into more smooth branches. All and all, you don’t want to reach for this woody tree when you need a grab.

Poison Hemlock and Spotted Water Hemlock

Don’t let their being a member of the carrot family fool you – these last two plants are deadly. Poison hemlock (Conicum maculatum) is native to Europe, Africa and Asia, but invasive in North America. Ranging from 6 to 8 feet tall, this biennial plant (meaning it takes two year to complete a life cycle) is known to grow in meadows, wetlands, ditches, and at the edges of cultivated fields. An easy way to identify the plant is by taking a gander at its stems which are hairless with distinct purple blotches. It also emits an odor, like mouse urine some say, but getting that close to the plant to crush it for a sniff is not recommended. With glossy, dark, fern-like leaves and the physical characteristics, hopefully reading this blog will be your only encounter with identifying this species.

Spotted water hemlock (Cicuta maculata) is native to North America and is often considered the deadliest plant on the continent. The tough part about identifying this species is that the size and color of stems can vary greatly, ranging from solid purple or green, to green with purple stripes or spots. When folks have taken a closer look, it has been noted that the vein pattern, ending at the base of the notch of the leaf edge, is a more reliable form of physical identification. As an obligate wetland plant, it occurs naturally in freshwater swamps, floodplains and marshes, and along banks and roadside ditches. Again, it is considered one of the deadliest poisonous plants in the United States, so keep your distance.

Some key commonalities to remember between these two treacherous plants are that both hemlocks:

You absolutely want to steer clear of both poison hemlock and spotted water hemlock as all parts of the plant are poisonous to animals and humans alike. Some symptoms can be vomiting, stomach pain, diarrhea, seizures, muscle damage, increased heartrate, or potential death (just to name a few). Depending on the exposure – ingestion, inhalation, or direct contact – the severe symptoms can appear as soon as 15 minutes up to a couple hours. These plants are no joke; save the best for last, they say.

So, are you scared yet? This write-up is not meant to frighten you, but rather inform you. A simple takeaway to consider in the field is this: don’t touch a plant if you aren’t 100% sure what it is! All good scientists use their eyes first. An outdoor journey can take you many places in Delaware, so being able to identify dangerous plants can keep your adventures safe and your eye for the natural world sharp. Let alone give you a few less trips to the local Walgreens for Caladryl or Tecnu.

Want to discover more about wetland plants? Check out the DNREC Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program’s Delaware Wetland Plant Field Guide.

Written on: July 26th, 2023 in Natural Resources, Wetland Animals

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Summer means warm weather (ok hot), spending more time outside, exploring the woods, wading in streams, and fishing. This makes it more likely that you will encounter one of Delaware’s 14 species of turtles! Safe to say that there is a turtle in every type of habitat you visit.

From saltwater rivers and bays to freshwater creeks, forested wetland ponds, dry forests, wet meadows, and freshwater ponds- there are turtles in everyone! But can you tell which one you’re seeing?Can you Name that Turtle?

Let’s start out in the dry upland forest and work our way out to the Delaware River and Bay, learning a few fun facts about six popular turtle species that call Delaware home and how to identify them.

Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina)

The box turtle is a common and attractive species found in forested upland habitat. They are small but noticeable because of their gold and black patterned shell. No two are the same and their colors and patterns vary widely. Their red eyes are sharp and help them locate food such as snails, insects, flowers, mushrooms, and worms. I once interrupted a box turtle munching on a mushroom for breakfast.

Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina)

Snappers can be found in many different habitats: slow moving streams, rivers, ponds, impoundments, and brackish or salt marshes. What makes them distinctive? Their size and shape. They are the largest Delaware species when fully grown, topping out around 35lbs and 18 inches long! They have a pointy snout, long tail, and large webbed feet. You may see them crossing or along the road – they come out of water to seek sandy areas to lay their eggs generally in May. Watch out for these adaptable reptiles on the road but keep your distance- they are known to be a bit defensive (and flexible) and will bite if threatened.

Bog Turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii)

The bog turtle is one you are NOT likely to encounter but it’s special and I had to include it. This petite and secretive turtle is only found in the eastern United States, and they are considered critically endangered. Bog turtles are the smallest in North America, reaching only 4.5 inches in length. They are dark brown and black mottled with a distinctive gold to orange patch on the side of their neck behind their eyes. Bog turtles are difficult to spot not just because of their size, but also their habitat. They favor open, groundwater-fed wet meadows and bogs dominated by sedges and grasses. Decline in this species is largely due to habitat loss and fragmentation, and meadows succeeding into forests.

Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans)

Red-eared sliders are recognizable in many freshwater ponds and rivers, and as a favored pet. They are distinctive by a broad red strip behind each eye. Although popular and common to see in the wild, they are a non-native invasive species in Delaware. Oftentimes, pet owners release unwanted pets into the wild, which contributes to their spread and risks spreading disease to native turtle populations.

Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata)

Spotted turtles are another small, aquatic species freshwater habitats, growing to between 3.5 and 5.5 inches (small enough to hold in one hand). Their dark smooth shell is marked with bright yellow polka dots. They prefer shallow freshwater forested ponds and spend more of their time underwater among leaf litter. In the winter, spotted turtles bury themselves deep in muddy sediment and enter brumation, where they slow heir metabolism drastically so they can live without food and very little oxygen. Like other species who rely on specific wetland types, spotted turtle populations are threatened by loss and fragmentation of habitat. Collection for the pet trade also poses a threat to them.

Diamondback Terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin)

This is one of my favorite turtle species in Delaware. Terrapins are unique in several ways. First, they are the only saltwater turtle in Delaware (not counting the odd sea turtle). The female is larger than males, measuring up to nine inches versus about 5.5 inches in males. They are common in the Delaware Bay and Inland Bays and are often spotted poking their heads up along tidal creeks and bays. They have a beautiful black and white spotted skin with distinctively light ‘lips’. They are meat-eating, and particularly enjoy menhaden and silverside fish. Unfortunately, many terrapins die each year as mistaken catch in crab traps, where they drown unless turtle exclusion devices are used. Many are also struck and killed on Route 1 in the Inland Bays as they cross the road to seek sandy nesting habitat.

If you are lucky enough to encounter any turtle in the wild, be gentle and let them be. Observe them doing their turtle thing, take some pictures but resist the idea to take them home. Wildlife belongs in the wild!

If you see a turtle crossing the road and want to lend a hand, carefully pick them (NOT by their tail) and move them across in the direction they were facing when you found them. Do this only if traffic allows safe conditions for yourself.

For more details on these turtles and more visit this turtle identification guide!

Written on: July 26th, 2023 in Natural Resources, Wetland Restoration

By Brigham Whitman, Delaware Wild Lands

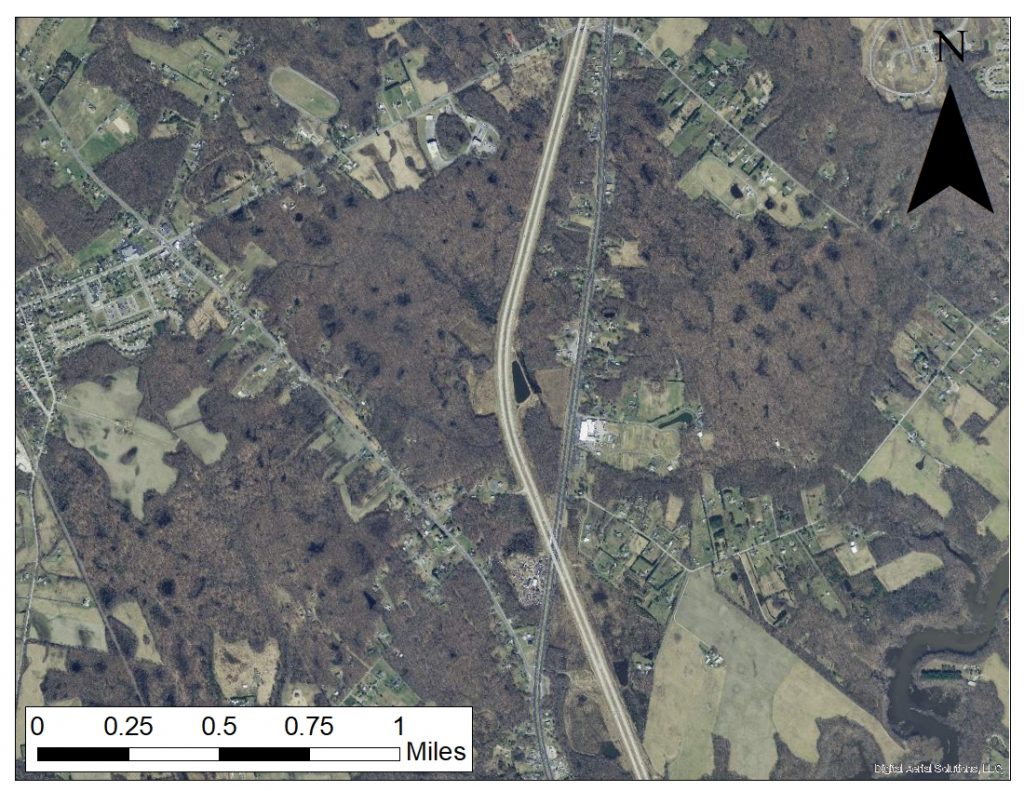

Taylors Bridge in southern New Castle County perfectly characterizes Delaware’s coastal flood plain: a mosaic of agricultural fields interspersed with patches of upland hardwood forest and the occasional residential development, surrounded by the waters of the Delaware Bay with fingers of marsh snaking throughout the adjacent low-lying areas. Aside from the natural beauty of the area, Taylors Bridge is also a highly biodiverse ecosystem, hosting 21% of the State’s flora in just 0.36% of the state’s land area. For these reasons, Delaware Wild Lands (DWL), the State’s oldest and largest land conservation organization, recently embarked on a major multi-phased effort to restore and connect natural habitats across DWL’s Taylors Bridge properties and protect the water quality of the Delaware River watershed. The first phase of this initiative, the now completed “NFWF Phase I” project, was funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) and at that point was the largest Federal grant DWL had ever received. Prior to this project, DWL typically focused on smaller grants because the organization was limited by its small staff size.

Last year, DWL and their partners, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Sarver Ecological, LLC, applied for and received a second, larger, and even more ambitious NFWF grant. In fact, this will now be the biggest Federal grant that DWL has ever received! This project, called NFWF Phase II, will rival the size and scale of DWL’s recent restoration projects at the Great Cypress Swamp in Sussex County. NFWF Phase II will add 75 acres of forest, seven acres of early successional habitat, and four acres of wetlands to the Taylors Bridge landscape. These restored areas will further connect and supplement the wildlife corridors that DWL installed in NFWF Phase I, thereby expanding the benefits of these corridors to new areas and additional wildlife populations. By utilizing a phased approach to restoration work, DWL can leverage the success of past grants to support current projects and produce results that might otherwise have seemed out of reach.

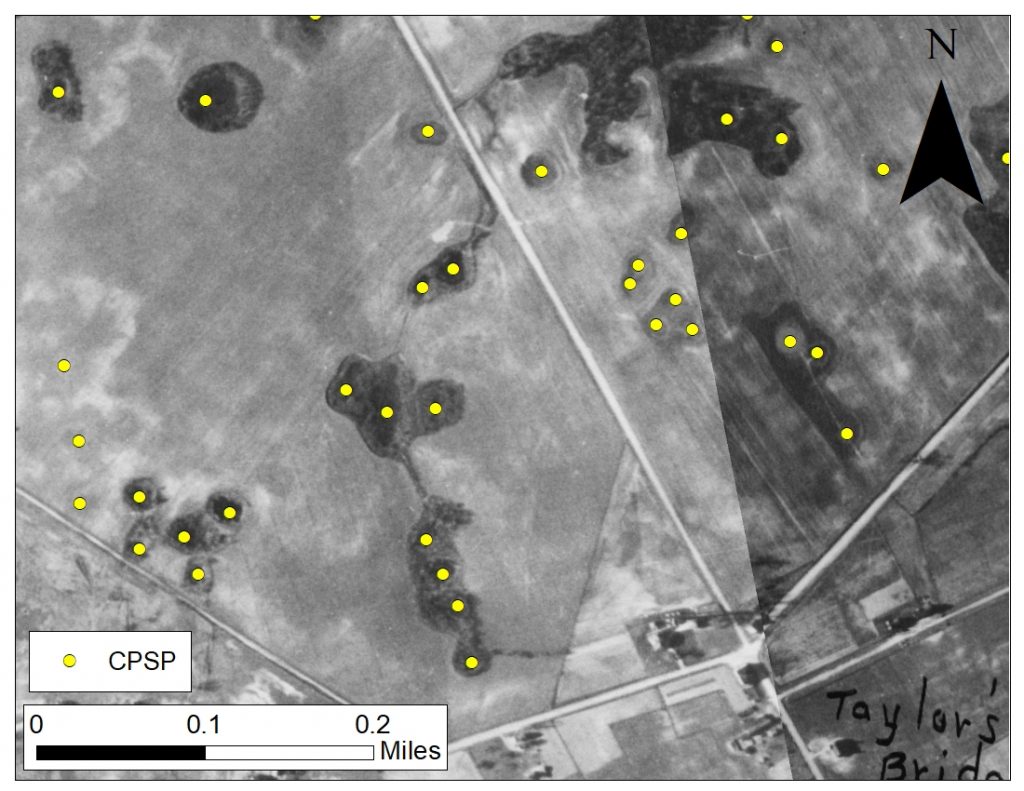

A major component of NFWF Phase II is the restoration of four acres of freshwater wetlands known as Coastal Plain Seasonal Ponds (CPSP), also called Delmarva Bays, Carolina Bays, or whale wallows. These ponds, which can be found across the eastern United States, are seasonal freshwater wetlands that are isolated from other water bodies. There are a number of theories about how these ponds formed, including meteor strikes, fish shoaling activity, or wind erosion during the Pleistocene Era. What is certain, though, is that without predatory fish, CPSP can provide unique habitat for rare and endangered species that can’t exist in other water bodies. CPSP were once a dominant feature on the landscape, and Taylors Bridge was a hotspot for these ponds. With the conversion of land for agricultural and residential use, however, many ponds were drained or filled-in. The CPSP that remain are now substantially threatened by development and sea level rise.

In preparation for the CPSP restoration, DWL staff referenced aerial imagery of DWL’s Dickinson Farm from the 1920s and performed subsurface soil investigations to determine where these ponds once existed. This year, staff will work with an excavator to restore the CPSP depressions to their original depth and place locally sourced tree stumps and logs to provide the structure necessary for a functional wetland ecosystem. DWL staff will then fill in the surrounding landscape with trees, grasses, and forbs.

Once NFWF Phases I and II are complete, the forested areas will serve as stop-over habitat for migratory songbirds and create a rare forest block in the region that will support forest interior dwelling wildlife species such as the wood thrush. The early successional habitat will benefit native bee and butterfly populations; provide habitat for snakes, turtles, red fox, opossum, skunk, and white-tailed deer; and support bird species such as the American woodcock, Baltimore oriole, indigo bunting, bobwhite quail, and turkey. The unique conditions in the CPSPs will benefit amphibians, reptiles, aquatic invertebrates, and rare insects and plants such as the state-endangered rare skipper, the amber-winged spreadwing, and the CPSP specialist plant American featherfoil. Farming activity will be streamlined as DWL makes a strategic effort to remove wet, marginal land from production in an effort to address sea level rise and manage the inland migration of marsh habitat on DWL properties. Furthermore, the trees and other vegetation that are planted will support conservation of the nearby marsh and protect the water quality of the Delaware River watershed. Landscape-scale conservation is a complex task, but DWL’s phased approach to conservation is achieving big results in Taylors Bridge.

To learn more about Delaware Wild Lands, visit dewildlands.org and follow them on Facebook and Instagram!

Written on: May 19th, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Natural Resources

By Joe Schell, DNREC’s Delaware Community Conservation Assistance Program

When you think of the word habitat – what is the first thing that comes to mind? Is it the dawn light painting your favorite meadow with wisps of amber and gold? Or maybe it’s the cool, crisp water of a stream full of fish and aquatic insects. For me it brings me to a warm spring morning in an old growth forest, as the trees fill with the sound of birdsong. Whatever you envision, the common theme is probably something that is far removed from people. But what if habitat didn’t have to be separate? What if habitat was your very own backyard?

Before homes, neighborhoods, towns, and cities there was just habitat – a home for plants and animals. When we consider it this way, thinking of our backyards as habitat doesn’t seem so out there. This is a big part of the reason we’ve seen urban conservationists advocating for homeowners to convert our backyards from traditional lawns to more natural landscapes like pollinator meadows.

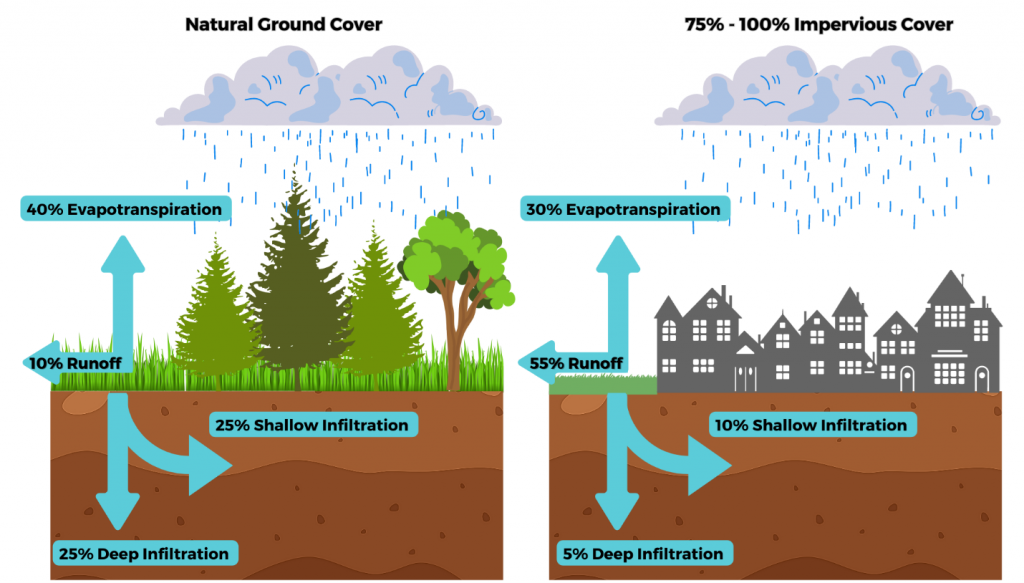

But habitat is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to benefits of native landscaping. Thinking of your backyard as an ecosystem has the added benefit of improving our watersheds! To visualize this, picture a rainstorm in a forest compared to a rainstorm in your town or backyard. They’re different, right? Some water can be absorbed in both, but much of the water in a neighborhood flows out or runs off through ditches and pipes. When this water enters our storm drains it takes any pollutants with it which eventually ends up in our streams, rivers, ands bays.

So, the trees we plant, gardens we tend, and practices we provide can not only create habitat, but also help clean and filter the water running off our homes, yards, and driveways. This all sounds great, but how do we go from lawns to landscapes? The “how” can take many different forms which we can call best management practices (BMPs). Let’s look at a few BMP examples.

Conservation Landscaping

Conservation landscaping is defined simply as the conversion of managed turf grasses to meadow. As a practice this has many benefits. These meadows provide our pollinating insects with important habitat. Beyond providing food, you also provide homes for beneficial insects. For example, sweet Joe-Pye weed (Eutrochium purpureum), in addition to its beautiful flowers, has stems that Delaware native bees love! These stems are hollow and during the winter months, native leafcutter (Megachile spp.) and mason bees (Osmia spp.) will use these as locations to lay eggs.

On top of these habitat benefits, landscaping with native plants instead of a managed lawn can promote healthier waterways. Most turf grasses used in lawns are not native to Delaware and can require maintenance like fertilizer, herbicides, and supplemental waterings. And for the volume of water a lawn needs, it doesn’t absorb that much of it increasing stormwater drainage needs. In some cases, 90% of the water that hits your lawn may run off it. Native plants are adapted to Delaware and don’t need as much maintenance to survive. In fact, once established and in the right habitat most native plants don’t need any supplemental waterings, all while absorbing excess water.

Rain Gardens

Conservation landscaping does a great job at reducing runoff, but a rain garden takes it to the next level! As the name suggests, these bowl-shaped gardens are designed specially to take in the excess stormwater from your home and lawn. The bowl shape design allows water entering the garden from your lawn, roof, and driveway to slowly infiltrate into the soil over the course of 24-48 hours. In terms of protecting our waterways, this is a huge benefit to water quality. Many of the major threats to water quality come from non-point source pollution – that is the small amounts of pollution such as sediment, oil, fertilizer, and other contaminants that wash away during storm events and eventually into our rivers and bays.

Plants in these practices are selected both for hardiness and their hydrophytic (wet-loving) nature. Native shrubs like inkberry holly (Ilex glabra), red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea) and perennials like blue flag (Iris versicolor), and swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) are perfect choices for rain gardens.

There is a lot more that goes into these practices when it comes to proper planning, installation, and maintenance. Fortunately, DNREC is offering a new program to help landowners on their water quality landscaping journey! The Delaware Community Conservation Assistance Program (DeCAP) provides both technical and financial assistance to homeowners, schools, and non-profits interested in practices like rain gardens and conservation landscaping. Whether you are looking to create habitat, improve water quality, or beautify your home, discover DeCAP and began your landscaping journey today.