Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube RSS Feed

Written on: May 19th, 2023 in Natural Resources, Outreach

By Joe Schell, DNREC’s Delaware Community Conservation Assistance Program (DeCAP)

When you think of the word habitat – what is the first thing that comes to mind? Is it the dawn light painting your favorite meadow with wisps of amber and gold? Or maybe it’s the cool, crisp water of a stream full of fish and aquatic insects. For me it brings me to a warm spring morning in an old growth forest, as the trees fill with the sound of birdsong. Whatever you envision, the common theme is probably something that is far removed from people. But what if habitat didn’t have to be separate? What if habitat was your very own backyard?

Before homes, neighborhoods, towns, and cities there was just habitat – a home for plants and animals. When we consider it this way, thinking of our backyards as habitat doesn’t seem so out there. This is a big part of the reason we’ve seen urban conservationists advocating for homeowners to convert our backyards from traditional lawns to more natural landscapes like pollinator meadows.

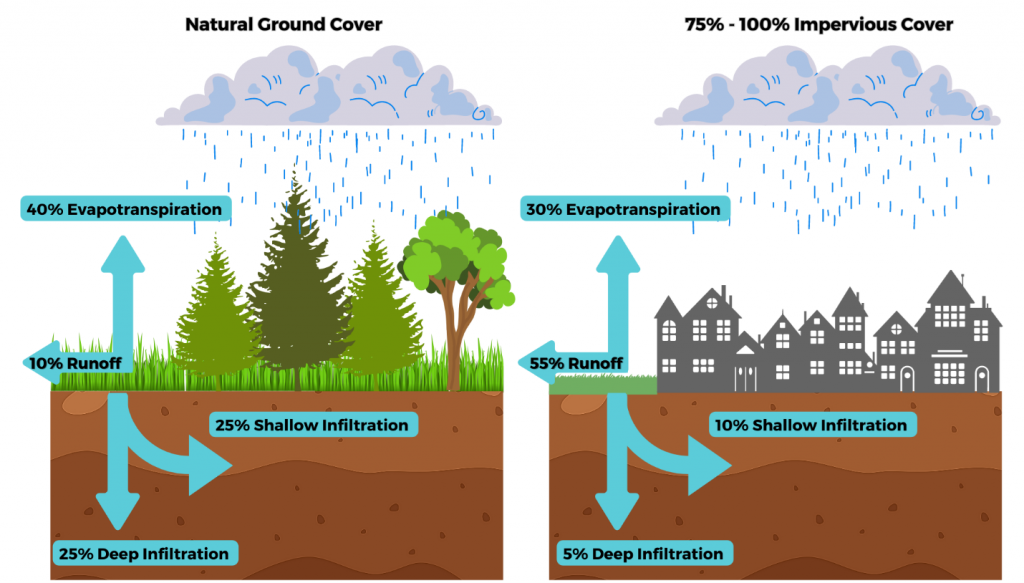

But habitat is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to benefits of native landscaping. Thinking of your backyard as an ecosystem has the added benefit of improving our watersheds! To visualize this, picture a rainstorm in a forest compared to a rainstorm in your town or backyard. They’re different, right? Some water can be absorbed in both, but much of the water in a neighborhood flows out or runs off through ditches and pipes. When this water enters our storm drains it takes any pollutants with it which eventually ends up in our streams, rivers, ands bays.

So, the trees we plant, gardens we tend, and practices we provide can not only create habitat, but also help clean and filter the water running off our homes, yards, and driveways. This all sounds great, but how do we go from lawns to landscapes? The “how” can take many different forms which we can call best management practices (BMPs). Let’s look at a few BMP examples.

Conservation Landscaping

Conservation landscaping is defined simply as the conversion of managed turf grasses to meadow. As a practice this has many benefits. These meadows provide our pollinating insects with important habitat. Beyond providing food, you also provide homes for beneficial insects. For example, sweet Joe-Pye weed (Eutrochium purpureum), in addition to its beautiful flowers, has stems that Delaware native bees love! These stems are hollow and during the winter months, native leafcutter (Megachile spp.) and mason bees (Osmia spp.) will use these as locations to lay eggs.

On top of these habitat benefits, landscaping with native plants instead of a managed lawn can promote healthier waterways. Most turf grasses used in lawns are not native to Delaware and can require maintenance like fertilizer, herbicides, and supplemental waterings. And for the volume of water a lawn needs, it doesn’t absorb that much of it increasing stormwater drainage needs. In some cases, 90% of the water that hits your lawn may run off it. Native plants are adapted to Delaware and don’t need as much maintenance to survive. In fact, once established and in the right habitat most native plants don’t need any supplemental waterings, all while absorbing excess water.

Rain Gardens

Conservation landscaping does a great job at reducing runoff, but a rain garden takes it to the next level! As the name suggests, these bowl-shaped gardens are designed specially to take in the excess stormwater from your home and lawn. The bowl shape design allows water entering the garden from your lawn, roof, and driveway to slowly infiltrate into the soil over the course of 24-48 hours. In terms of protecting our waterways, this is a huge benefit to water quality. Many of the major threats to water quality come from non-point source pollution – that is the small amounts of pollution such as sediment, oil, fertilizer, and other contaminants that wash away during storm events and eventually into our rivers and bays.

Plants in these practices are selected both for hardiness and their hydrophytic (wet-loving) nature. Native shrubs like inkberry holly (Ilex glabra), red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea) and perennials like blue flag (Iris versicolor), and swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) are perfect choices for rain gardens.

There is a lot more that goes into these practices when it comes to proper planning, installation, and maintenance. Fortunately, DNREC is offering a new program to help landowners on their water quality landscaping journey! The Delaware Community Conservation Assistance Program (DeCAP) provides both technical and financial assistance to homeowners, schools, and non-profits interested in practices like rain gardens and conservation landscaping. Whether you are looking to create habitat, improve water quality, or beautify your home, discover DeCAP and began your landscaping journey today.