Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube RSS Feed

Written on: July 13th, 2022 in Outreach, Wetland Animals

By Laurel Sullivan, DNREC’s Delaware Coastal Programs

Attention! Calling all birders, experienced and newbies- the Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve (DNERR) has a Big Year challenge for you!

A Big Year is a challenge birdwatchers set for themselves to see or hear as many birds and bird species as possible within a single year. This is a personal goal or informal competition taken on by birders to see as many species and individual birds as possible within a given year and geographic area. DNERR is excited to host our own Big Year challenge in 2022 at our two locations, the Blackbird Creek Reserve and the St. Jones Reserve. Documenting the species of birds that visit the Reserves’ locations will allow us to collect data on common and rare species, while also increasing awareness about these estuary ecosystems.

Where Can You Bird?

The DNERR’s locations have dynamic habitats that offer many resources for a variety of bird species. The Blackbird Creek Reserve, located in Townsend, is a freshwater marsh with meadows and many native tree species that have been planted as part of our conservation and stewardship efforts. The St. Jones Reserve, located in Dover, is a salt marsh offering a preserved land area for many marsh birds. These two locations, with their differing habitats, resources and bird populations, will allow variety in the recorded sightings, helping our Big Year flourish! Both reserve components have walking trails available for birders to utilize while they are participating in our Big Year. The Blackbird Creek Reserve even has specified bird watching stations for visitors to make use of as they look for birds that may be wading in the Blackbird Creek.

What Birds Might You See?

Each of the habitats at DNERR’s locations have many resident species, which are birds that are commonly seen year-round. Some resident species are the American Robin, the Great Blue Heron and the Bald Eagle. However, the habitats also offer unique resources as the seasons change, attracting migratory bird species. DNERR does have some commonly seen migrating birds, such as the Red Knot, Dark-eyed Junco, and Canada Goose. By continually engaging with the public and the birding community, DNERR is hoping to capture the seasonal shifts of bird populations. We are also excited to document any rare species that may be sighted throughout the year. This information collected during the Big Year will help to inform restoration plans, land stewardship and conservation efforts.

How It Works

At the Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve, research is our middle name. That is where you come in. DNERR’s Big Year could not be done without the help of everyone who visits the Reserves’ locations. Participation in the Big Year is relatively easy; you do not have to be an experienced birder to get involved and become a citizen scientist – all you need is your smartphone. The Reserve will be utilizing two platforms – iNaturalist and eBird – to capture and record the data. The platform, iNaturalist, allows participants to upload individual sightings with pictures or audio. These sightings can then be verified and confirmed by other users and Reserve staff through the app. This makes iNaturalist a great option for beginning birders! The platform, eBird, commonly used by more experienced birders, provides an opportunity for users to populate a personal list of birds. Birders can use the Reserves’ hotspots to see recent sightings from other users as well.

While each birding adventure will be unique and your own, we ask that you follow the Big Year challenge rules below, which are based on the American Birding Association guidelines:

We want all birding participants to remain safe, please follow the safety guidelines below:

We at DNERR are very excited about our Big Year and the data that we will use for years to come to enhance our species inventory. We hope that this challenge inspires many new and experienced birders to explore the estuary. Become a Big Year Birder with DNERR today!

For more information about DNERR’s Big Year and how to become an official DNERR Big Year Birder, please visit our website. We look forward to seeing you out on our trails!

Written on: July 13th, 2022 in Outreach

By Ashley Cole, Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

This summer I’ve had the amazing opportunity to work with DNREC’s Department of Watershed Stewardship, specifically their Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program. I was very excited to get outdoors, see wild places no one has seen before, and keep our wetlands healthy. I thought these wetlands would be mostly free of trash based on how far away they were from where people would be. However, upon our first site visit of the season, all the way down in the Pocomoke watershed, I noticed the amount of trash that we found seemingly in the middle of nowhere. Our phones had no service and we were several hundred meters into the woods. How could trash have gotten there? I was shocked to find anything from candy wrappers to Royal Farms chicken boxes, to even old plastic soda bottles and cans. Seeing all this trash made me realize the damaging effects of littering and not disposing of trash properly. We all know that most waste leads to the ocean or other waterways, but to a wetland in the middle of the woods? Seems like there needs to be a change. As humans we often think that our small decisions have no actual impact on the environment. That if one person decides to do the right thing, it won’t make that big of an impact in the end. But believe it or not it can. All this trash that is being pushed into our wetlands came from somewhere and someone. If the trash would have been disposed of properly, it would not be in our wetlands.

The Importance of Wetlands

Wetlands play a key role in our everyday lives. Wetlands help prevent erosion of our shorelines, and help prevent flooding on the coasts as well as inland. Wetlands are home to so many important and beneficial plants, animals, and other organisms. Wetlands help remove pollutants from the water keeping our waterways clean. Wetlands also act as an air filter, grabbing CO2 and other air pollutants, like greenhouse gasses out of the atmosphere. As you can see, wetlands play a vital role in a healthy everyday life. But if trash keeps ending up in our wetlands, these important services will be diminished or eliminated. Wetlands choked with waste can hardly serve as good wildlife habitat. It is up to us to keep them clean and healthy.

The Impacts of Waste in Our Wetlands:

You might be wondering, how does a thrown-out plastic bottle, or a plastic shopping bag that end up in our wetlands cause any harm? Plastics are made up of many harmful chemicals that can be harmful to both human and animal health. When plastics are exposed to the sun they will begin to break down, the harmful chemicals will detach from the plastic and into the environment, this process is called chemical leaching. As the plastic is in nature, the plastic itself will also break down into small pieces called microplastics. Microplastics are increasingly becoming more of a threat to human and environmental health every day; it is in this form that plastics are even more dangerous and harmful. These microplastics end up in our oceans, being consumed by fish, which are then consumed by humans. Filling our ecosystems and food chains with harmful and toxic chemicals. These microplastics which leach even more harmful and concentrated chemicals can leach their chemicals into our groundwater and streams. Creating toxic drinking water for both humans and wildlife.

Other impacts humans have had on wetlands when it comes to not disposing of waste properly is by dumping waste fluids into the woods or in areas that is not seen by the general public, as an out of sight out of mind area where no one will care. Dumping harmful, and toxic substances, like oils, grease, and chemicals into the woods, has the potential to harm wildlife as they could accidentally consume it, get it on their fur or skin, or leach into the ground, poisoning the plants in which wildlife need to survive. These waste substances can also leach into the soil and down into our groundwater, once again causing a potential for harming the water quality of our drinking water, or the water quality of streams and oceans.

What You Can Do To Help:

There are many ways you can help keep our wetlands clean! One of the most impactful ways you can help decrease the amount of trash and plastics from entering our wetlands and environment is by decreasing your use of single use plastics. Fighting the war on pollution can start in the home! Before going to the grocery store, bring your own reusable bags to use instead of using the grocery store’s plastic bags. This can greatly reduce the number of plastic bags from being disposed of improperly that eventually end up in our natural areas. Decreasing the number of times, you eat at fast food restaurants who use products like styrofoam cups and food containers can also play a beneficial role in lowering the amount of trash in our wetlands. When purchasing soft drinks, try to find a store that allows you to fill up a reusable cup you had from home, rather than using a plastic cup they have in the store.

Of course, always disposing of your trash responsibly is a big one. Don’t litter and just leave your trash where it is. This is one of the main causes of how trash is ending up in wetlands. Trash on the ground can move into wetlands during storms due to runoff caused by rain or wind. By disposing of your trash properly, it will ensure that the trash is contained and taken care of responsibly. Another way you can help keep wetlands clean is by recycling the correct items that can be recycled. Always check the labels of plastics, papers, carboards, etc., that you are considering recycling. There are often different codes or ways in which an item can be recycled and identify if they can be recycled at all. By checking these labels and recycling properly you can help prevent trash and other pollutants from entering our wetlands.

When recycling, it is important to make sure whatever you are recycling is free from any left-over food debris and is cleaned out. When placing your recyclable items into your recycle bin or whatever you use to hold your recyclables, make sure that they are placed loosely into the bin and not bagged, as plastic bags cannot be recycled. Recycling is a very important effort that we can try to contribute to make Delaware and our planet a healthier, cleaner place. Recycling greatly reduces greenhouse gas emissions from entering our atmosphere, it conserves our natural resources and energy, and it helps keep our planet clean from not placing even more trash into already full landfills and trash dumps.

There are also plenty of useful and innovative ways you can reuse recyclables before putting them into the recycling bin. This is where their recycling codes come into play. On many different plastics and recyclable items, there will be a recycling symbol on the back, bottom, or one of the sides. Inside of this symbol will be a number. This number corresponds to the type of chemicals that were used to create this plastic. Some chemicals are toxic and not healthy to use for human consumption after its first use, and others can be safely used more than once. Some ways you can reuse plastics is by finding new ways they can be useful. For example, you can take a plastic liter bottle, cut it in half, and use the plastic as a planter. If you have young kids, there are plenty of cool arts and crafts ideas you can do, that uses left over plastic containers. The possibilities are endless! And you have created something new out of something that would have just been throw away.

Another way you can help protect our wetlands and keep them clean is by getting involved. Volunteer for cleanups around your city or beaches, contact state environmental agencies, like DNREC, to see how you can help. If you live near a shoreline, consider having a living shoreline. You can use non-toxic, unbleached, and phosphate free cleaning supplies, detergents, and lawn care products to prevent toxic chemicals from entering into our waterways and wetlands. Or if you see something, say something. If you see someone liter, say something to them and educate them on why they shouldn’t liter. With these steps in mind, you can become a wetland steward and feel good about the positive impact you are having on the cleanliness and health of Delaware’s wetlands!

For more information on recycling, please visit DNREC’s “How to Recycle Guide” and other useful information.

Written on: July 13th, 2022 in Wetland Assessments

By Brittney Flatten, DNREC’s Watershed Assessment and Management Section

This summer, the Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program (WMAP) team is doing wetland condition assessments in the Pocomoke River watershed. During an assessment, scientists look at soil quality, rate sources of water, evaluate the plant community, and identify stressors in or around the wetland. These observations help determine if the wetland is healthy and functioning. This work is part of WMAP’s ongoing project to assess wetlands in every watershed in Delaware and the Pocomoke is last on the list! Because the Pocomoke watershed is a small and relatively remote part of our state, it doesn’t always get the attention it deserves. Let’s take a moment to learn about some unique natural features in this part of Delaware.

Plant Communities in the Pocomoke

The Pocomoke watershed is home to the Great Cypress Swamp. According to Delaware Wild Lands, it is the largest freshwater wetland and contiguous block of forest in Delaware. At its largest, it was probably 60,000 acres, but much of that has been lost due to timbering and drainage for agriculture. A few years ago, our blog featured a post from Delaware Wild Lands about wetland and habitat restoration in Great Cypress Swamp.

As you might’ve guessed from the previous fact, some swamps in the Pocomoke watershed have bald cypress trees. Bald cypresses tolerate being partly submerged in water so they can live in very wet conditions. You can spot cypress trees in wetlands by their knees- woody structures that grow aboveground. Scientists haven’t reached a consensus on the purpose of knees, but one hypothesis is that knees help provide extra stability in soft, wet soils. For even more support, bald cypress trees have buttressed roots which flare out at the bottom of the tree compared to typical straight trunks. Bald cypresses are also deciduous conifers, so they drop their needles every year unlike evergreen conifers which keep their needles year round. The Great Cypress Swamp and Trap Pond State Park in the neighboring Nanticoke watershed are thought to have some of the northernmost natural bald cypress stands in the United States. These unique ecosystems are much more common further south in the Carolinas and Louisiana, but you can find them right here in the first state!

You may come across Atlantic white cedar swamps in this part of Delaware too. These swamps typically have a mix of Atlantic white cedar, gum, and maple trees. They are important habitat for sphagnum moss and even rare insect-eating carnivorous plants!

Want to explore other plant communities in Delaware? Check out University of Delaware’s Statewide Vegetation Community Map.

The Deep and Dark Pocomoke River

The mainstem of the Pocomoke River is known for its dark and sometimes mysterious appearance. The small headwater tributaries are in the Great Cypress Swamp, but further downstream before draining into the Chesapeake Bay, the Pocomoke can reach depths of 45 feet, which is rare for a river that is less than 100 feet wide. Most of Delaware and Maryland’s eastern shore are in the coastal plain ecoregion, where land is flat and near sea level, so rivers have a low slope and move slowly. When combined with the presence of large, forested wetlands, conditions can create blackwater streams. The leaf litter from cypress and cedar wetlands decomposes very slowly in low-oxygen waters and releases tannic acid into nearby streams, which gives the water its dark, yet clear appearance. Blackwater streams will naturally have lower dissolved oxygen and are more acidic, but there are still plenty of fish, reptiles, and amphibians that like to hang out in these ecosystems.

Preserving the Pocomoke

DNREC scientists in the Divisions of Watershed Stewardship, Fish and Wildlife, and Parks and Recreation all work to preserve unique natural areas in Delaware, through assessing wetland condition, documenting plant and wildlife communities, and protecting land with conservation areas, easements, and more. Non-profit organizations like Delaware Wild Lands and The Nature Conservancy work to preserve and restore cypress and cedar forests in Delaware and Maryland’s lower eastern shore. You can get involved too by learning more about protecting Delaware’s wetlands and watersheds. If you want to see these cool ecosystems in action, visit Trap Pond State Park or Pocomoke River State Park in Maryland. You can also learn more on the Delaware Wild Lands page for Great Cypress Swamp.

Results from previous assessment years and watersheds can be found in our library.

Written on: July 13th, 2022 in Outreach

By Olivia Allread, Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Science and reality of our current times shows that certain groups in society carry unequal economic and environmental burdens. The food we eat, the air we breathe, our water sources, and indeed our overall health depend on a clean and sustainable environment. Unfortunately, the benefits of an equitable life are not always shared. Many areas across the nation predominantly made of racial minorities and low-income communities still face challenges with accessing those everyday needs or environmental education. The movement in the United States, and really across the world, to recognize and protect the right to a healthy, clean, and sustainable environment is what is called Environmental Justice (EJ).

Environmental Justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people, regardless of race, color, national origin or income, with respect to the development, implementation and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations and policies; and the equitable access to green spaces, public recreation opportunities and information and data on potential exposures to environmental hazards.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

Although this concept is being focused on now more than ever, the roots of EJ span back to the late 1960’s in the United States, primarily started by people of color. Events during the civil rights and social injustice movements ignited the concept of EJ on multiple levels of society – grassroots, locally, and regionally. The principles set forth stemmed from events such as when Latino farm workers in California fought for workplace rights and safety, or when African American students in Texas protested a city dump in their community. There was movement on the rise during that time that laid the foundation for more organized efforts by minorities to stand up and speak out.

EJ Across Nation

Environmental justice concerns exist all over the country, from urban areas to isolated rural towns. Many low-income neighborhoods and communities of color experience disproportionate impacts involving natural disasters, access to green space, and education. These wide-ranging issues contribute to the gap between “those who have” and “those who have not”. Certain areas may struggle with long-term sustainability, while others are left without the means to improve their situation or environmental education. Some of primary challenges communities at risk face involve:

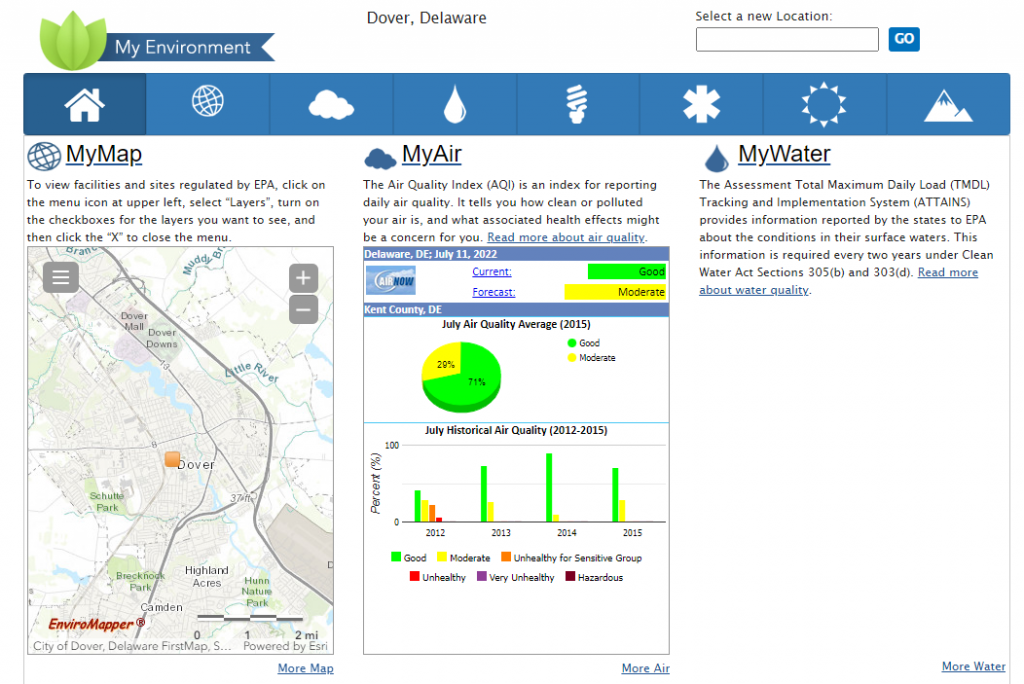

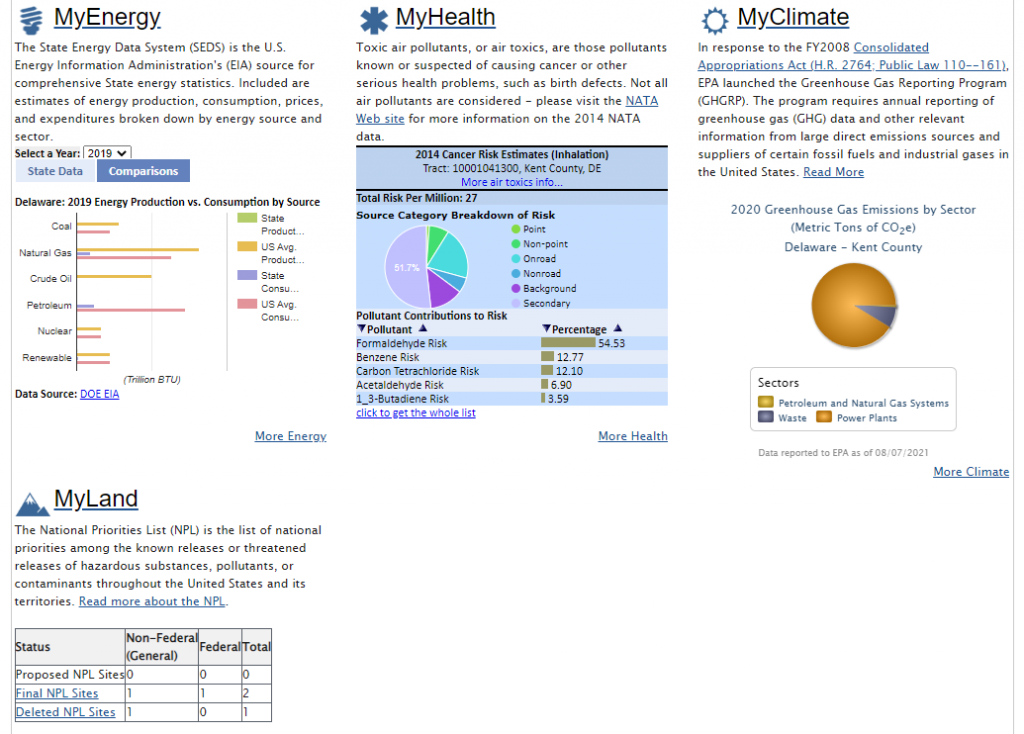

A key component in addressing EJ concerns is being able to identify the under-served and under-represented communities. On a national level, resources are emerging to ensure that people at risk have a seat at the table in their own future. The EPA EJScreen is an innovative tool that allows users to access a lot of environmental and demographic information in the United States. A user can identify anything from potential environmental quality issues to unemployment rates to traffic proximity. With the MyEnvironment tool, get as specific as your own zip code. This application is more than meets the eye when it comes to what you have access to; users of this tool can see over 60 different of categories of accessible data. Food waste, UV index, energy production, clean diesel programs, cancer risks, and surging seas just to name a few. On an individual level, states and organizations have developed similar mapping tools to focus in on what populations are at risk and what areas need the most change. Through these more specified datasets, stakeholders and community residents alike can expand there efforts into research or even policy. Current resources are out there waiting to be used, start with a simple google search to see what you find.

EJ in Delaware and with Wetlands

Let’s take it to more of a local scale. In Delaware, like many other places trying to navigate EJ, it is a work in progress. Though the first state is small, the variety of vibrant communities in each county deserves representation to the fullest.

A good place to start digging is the state of Delaware’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI). Social Vulnerability is the extent to which an area’s social conditions affect the response and prevention of natural disasters. With all the movement occurring with climate change and population booms in Delaware, the rankings calculated could help with future planning of socially vulnerable communities. DNREC currently has an internal EJ workgroup dedicated to actions and recommendations that address the areas of service, engagement and outreach. The group is even in the process of creating an EJ mapping tool with in-depth Delaware specific information. Other independent organizations have come out of the woodwork as well. Since 2011, the Delaware Concerned Residents for Environmental Justice has been taking a bottom-up approach of decision-making while trying to unite other grassroots and environmental organizations throughout the state. There are even partnership organizations, such as Healthy Communities Delaware, that feature missions involving work with the community rather than for the community.

When it comes to wetlands, integrating EJ practices into program development while focusing on meeting the needs of underserved communities is a critical tool to build wetland stewards. Vulnerable areas are exposed to social and environmental stressors, but have limited capacity to alter their relationship with them. An important step in the right direction is to empower the concept that anyone has the right to and can change their connection with the environment. Whether it be educating rural populations on wetland benefits, or speaking with urban planners about wetland adaptation and mitigation efforts, everyone has to be included in the conversation. Especially the populations experiencing the most discrepancies and challenges. These kinds of tactics can trickle over to wetland outreach, permitting, city planning, enforcement, you name it. Digital and on-the-ground tools can be utilized together to increase awareness of wetland ecosystems while reducing disparities. EJ provides inclusiveness for all to engage in and shape their understanding of wetlands and why to protect them. The ability to raise awareness about environmental degradation or inequities may very well elevate the voices most affected by them.

What Does The Future Hold

The importance of EJ spans far beyond the reaches of our country’s borders. In October of 2021, the United Nations Human Rights Council adopted a resolution recognizing that a healthy, clean, and sustainable environment is a basic human right. Recognition is the key word here. With more than 150 countries standing behind the concept of this inherent right, the United Nations General Assembly could bring about more ambitious and coordinated action to protect the environment for underserved and underrepresented communities. As the main policy-making sector of the United Nations, the Assembly can use this recognition at many levels of policy and law potentially creating government action and responsibility.

For those who have traditionally lived, worked, and played closest to sources of pollution or social inequalities, the stakes are high. An area’s ability to have successful business and economic stimulation, combined with a sense of representation, can go hand-in-hand with the well-being of its people. The history of the environmental justice movement has already proved that progress can be made with community advocacy backed by back science and the law. Bring in determination and innovation, and we’ve got ourselves a path forward for effective decision making. The dots have been connected. Whether it be in Smyrna, Delaware or Sir Lanka, EJ represents rights that should exist to all of us inherently. Who better to stand up for our communities than the people who live and thrive in them.

Want to see examples of EJ in action? Browse through the resources below to see what is happening across the United States.