Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube RSS Feed

Written on: March 17th, 2022 in Wetland Animals

by Alison Rogerson, Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

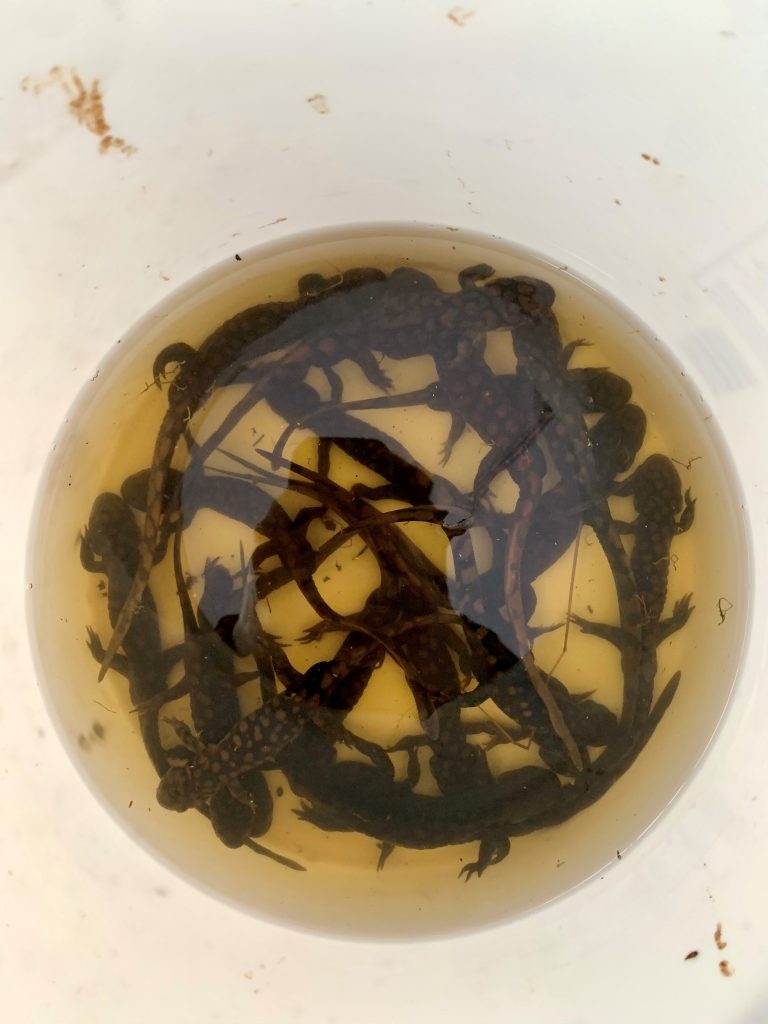

Early on a rainy but relatively warm February morning, while most people were still snuggled under the blankets, two biologists from DNREC Fish & Wildlife wade through a wetland pond in Blackbird State Forest. Their chest waders and raincoat keep them dry. Their headlamp helps them navigate in the early light around stumps and shrubs as they shuffle around the pond checking traps set the evening before. What are they after? The Eastern tiger salamander, one of Delaware’s rarest amphibians.

Today’s catch has been good, 100 individuals captured in this one large pond. There are several other ponds to check, yielding several hundred in total for the day. I pull up to the forest area parking lot hours later, well-rested, caffeinated, and ready to help with the detailed process of measuring and recording data on each salamander before releasing them. Life history data such as sex, length and egg bearing-status are recorded for each creature. A photo is taken as well, to be sorted and matched up with photos from previous years- a tedious task that helps biologists identify individuals by their markings.

All of this information is used to help DNREC count and track local populations of this state endangered amphibian. Timing is critical. Tiger salamanders are the first species to come out of winter brumation (that’s hibernation for cold-blooded species) in nearby forests to gather in vernal ponds to breed and lay egg masses. Their internal clock is motivated by warm rain in late winter to early spring. They may only hang out in ponds to breed for one or two weeks before heading back to upland forested habitat.

Tiger salamanders historically ranged from southern New York to northern Florida, but is now endangered in New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, is essential gone from Pennsylvania, and are of special concern in North and South Carolina. Their number one threat is loss of habitat. Clearing forests and removal of forested buffers around seasonal ponds leaves them no where to go. Although seasonal ponds normally dry up at the end of the summer, droughts and shifts in normal rain patterns due to climate change also increase mortality.

What can you do? Plant more trees! If you own forested property, leave logs and downed trees in place- they make good salamander hiding places. If you own a seasonal pond, be sure to keep a wide forested buffer around them. Resist the urge to clear and mow up to the edge. Lastly, encourage the protection of freshwater wetlands and buffers statewide and by county.

Written on: March 16th, 2022 in Wetland Assessments

By Alison Rogerson, Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

By now, you may have read through our previous Status and Trends blog posts focused on current acreage, or status, of wetlands, as well as trends such as gains and losses. There is still one trends category to dive into: changes. This is probably the most difficult category for us to summarize and report on. It comes down to the details, looking back and forth from older maps and photos to more recent ones. It’s also the least intuitive category of wetland trends for readers to recognize. How do wetlands change? Why is it important to track if they are still wetlands? Let’s jump in.

The changes category focuses on wetlands that have, no surprise here, changed over time, in this case between 2007 and 2017. Their boundaries haven’t moved, that would be a gain or a loss. This category takes a closer look at how existing wetlands are shifting and why. This may seem like splitting hairs, but a total of 13,822 acres of wetlands changed from one wetland type to another from 2007 to 2017 statewide. That’s about 4.6% of Delaware’s wetlands statewide. Definitely a topic worth keeping track of.

Of those 13,822 acres, 6,169 acres of changes occurred in tidal wetlands (44%) and 7,652 acres (55%) were in non-tidal wetlands. We divided them into four groups, mostly using changes in cover or vegetation as an indicator. It’s interesting to think about what factors could lead to a wetland change.

Shifts in Water Type

This group covers two areas: changes in water regime from Palustrine (or freshwater) to Estuarine (saltwater) and changes in tidal pattern from nontidal to tidal. Changes in hydrology accounted for 2,100 acres and confirm to us that water levels are rising and saltwater lines are moving further and further inland. Exposure to tides and salt water permanently alters the plants and animals that can live there. In this group, we can see how the relatively rare tidal freshwater wetlands and being pushed further inland until they will become pinched out at the base of created lakes and ponds.

Vegetation Growth

While most changes were because of a loss of vegetation, we also documented a small amount of growth. Accounting for only 10% of overall changes, plant growth from muddy or bare bottom into emergent vegetation, or growth in lakes and ponds occurred equally in tidal and nontidal wetlands.

Vegetation Loss

Loss of vegetation made up almost 1/3 of all wetland changes and was seen predominantly in tidal wetlands (94%). In these cases, tidal wetlands used to have grassy emergent plants but changed into muddy or bare bottom areas. This could also be related to sea level rise and erosion. Once coastal areas are bare and lack roots to hold soils together, they are vulnerable to further erosion and loss of shoreline habitat completely. This is a natural process being amplified by climate change that is being documented at an alarming rate along the east coast.

Vegetation Shifts

Shifts in the vegetation community can go both ways; plants growing in and up but also plants dying off or back. This was the biggest group for changes, accounting for 44% overall, and 90% of the time occurred in nontidal wetlands. Succession is a natural process and can happen when a grassy wetland grows into scrub shrub habitat over time. Alternatively, as we see water levels and flooding increase, we also see vegetation dying off, reverting from a forested wetland to an emergent wetland, sometimes becoming an expanded floodplain along a river. Lastly, deforestation was also a major source of vegetation shifts in nontidal wetlands, stemming mostly from timber harvesting. Sometimes those areas recover and revegetate over the years but often suffer from the physical impacts of harvesting.

Although these changes may seem really detailed, they can help us track the less obvious processes affecting wetlands in Delaware. Perhaps the acreage in an area didn’t change much but the make up of those wetlands tell us they are going through a downward process towards a loss. Keeping trends straight between tidal and nontidal systems is important too, as we decide how to protect and restore them.

Written on: March 14th, 2022 in Outreach

By Caitlin Chaney, Delaware Center for the Inland Bays

In the last 30 years, the population across the Delaware Inland Bays watershed has surged. The Inland Bays is a special place to live, but growing development brings challenges to the watershed and those who live within it. Climate change, sea level rise, and nutrient pollution all pose threats to the Inland Bays.

The good news is that everyone, including property owners, have the opportunity to help care for our shared paradise in a way that benefits the ecosystem and community. The Delaware Center for the Inland Bays (Center) recently published Protecting the Inland Bays: A Waterfront Property Owner’s Guide, an educational resource that addresses some of the most persistent threats facing the Inland Bays and their watershed. It offers guidance on how to protect and enhance properties while promoting healthy shorelines and nearshore areas, water quality, and habitats for both people and wildlife. Below is a summary of some of the guidance provided within the publication.

First Steps:

A critical first step is informing yourself of the rules and regulations regarding your property. The Center recommends checking your deed restrictions, reviewing the appropriate HOA governing documents (if applicable), and researching town and county ordinances and state regulations and guidance.

Minimize Runoff and Groundwater Contamination

Small adjustments on your property can make a big difference in reducing polluted stormwater runoff and groundwater. Here are some best practices:

Create Your Very Own Nature Preserve

You can help restore the delicate balance of the local ecosystem while creating a beautiful oasis right in your backyard.

Managing Septic Systems & Wastewater

Proper maintenance and management of your septic system and wastewater is essential to preventing contaminants and excess nutrients from entering groundwater.

These tips are just a few ways that property owners can simultaneously help protect the Inland Bays and their watershed and their investment. To access more in-depth guidance and information, including the benefits of living shorelines and enhancing buffers, please click here to download the Center’s waterfront property owner guidebook along with supporting resources.

Printed copies are also available upon request by emailing cchaney@inlandbays.org.

Written on: March 14th, 2022 in Outreach

By Olivia McDonald, Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Finally, it’s here! The holiday we all have never really heard of. It might be true that only folks working in the realms of nature know of this environmental festivity. So I figured hey, why not spread the word on something that actually impacts every single one of us – water.

World Water Day has been celebrated every year since 1993, and was created by the United Nations to celebrate water and raise awareness for people across the globe who currently are living without access to safe water. Now the words “safe water” can come in many different shapes and sizes. We are talking about things like drinking water, basic sanitation, bottled water, public facilities, surface, springs, recreational waters, the list really can go on. March 22 is the day, and this year’s theme of World Water Day is groundwater – making the invisible visible.

Right off the bat, let’s get started with some basics. What exactly is groundwater?

Groundwater is water found underground in aquifers, which are geological formations of rocks, sands and gravels that hold substantial quantities of water. Groundwater feeds springs, rivers, lakes and wetlands, and seeps into oceans. Groundwater is recharged mainly from rain and snowfall infiltrating the ground. Groundwater can be extracted to the surface by pumps and wells.

World Water Day 2022, United Nations

That definition gives me an overarching sense that what we do as humans on the surface matters underground. Since most of the liquid freshwater in the world is groundwater, choices big and small can affect things like farming, drinking sources, city sanitation systems, or animal populations. Countries with very arid climates often solely depend on groundwater for everyday use. Currently, the United Nations estimates that 40% of all the water used for irrigation of any type comes from aquifers created by groundwater – that is a rather demanding source! And of course to have a functioning ecosystem, such as a wetland or river, you need healthy water. Some of this may seem more like a third world problem, but impacts from fracking or places like Flint, Michigan show us that even in the United States water issues can become a major concern.

You might remember back in grade school learning about the water cycle, and how water in different forms takes certain paths yet is still all one thing. Well it really is. Lakes, rivers, ponds, streams, and wetlands are all within this hydrologic system of waters that are continually connected. When it comes to groundwater there is recharge and discharge. Recharge is when water seeps into the ground to replenish aquifers, and discharge occurs when water emerges from the saturated ground. Luckily wetlands do a little bit of both, but more often, groundwater discharges into our wetland areas. Either function the wetland performs adds value to the relationship of our water and land. Take a look at the benefits below;

Many places that the citizens of Delaware enjoy – publicly owned parks or state natural areas – contain water dependent on the success of this hydrologic system. In fact, most of the state’s public water supply comes from groundwater. Then we have our Category One wetlands which make up a small percentage of all of Delaware’s wetlands. These are very uncommon, unique freshwater areas like groundwater seepage wetlands. Seeps, as we like to call them, occur in areas on slopes or along slope bases where groundwater flows out onto the surface. Category One wetlands are home to complex habitats and rare plant and animals species, such as the Bog turtle (glyptemys muhlenbergii). I certainly want to keep that cute critter to the right around. As for humans, these wetlands are not only rich in plant and animal biodiversity, but also provide benefits for flood storage and water quality, simply through the groundwater coming to the surface naturally.

Honing in on groundwater for this year’s World Water Day means remembering that we need to strike a balance between the peoples’ needs and the planet. Continuous over-use of groundwater leads to the depletion of the resource. Overexploitation can lead to land instability and subsidence, particularly in our coastal regions of Delaware where salt water intrusion is occurring. Adaptation and policymaking should reflect the sustainable development for waters of all types. With the spotlight shining more and more on environmental changes, management and governance tools are being developed to combat the pressures of resource availability. Since groundwater is already so vied for, it is imperative to understand its role in sanitation systems, industry, agriculture, climate change, and ecosystems for the future.

Just because something is beneath the surface, doesn’t mean it has to be out of your mind. Wetlands and groundwater, like all the other wonderful natural resources we possess, are not infinite. It starts with you. In your backyard, in your reusable water bottle, in what kind of jeans you choose to wear (Google water and jeans, trust me). Calculate your water footprint to determine how your production and consumption choices affect natural resources. Clean up your local water source with a crew of friends. Every little bit counts, it doesn’t just have to happen on March 22.

To find out more about World Water Day, please visit https://www.worldwaterday.org/

Written on: March 14th, 2022 in Outreach, Wetland Animals

By Kayla Clauson, DNREC’s Watershed Assessment and Management Section

If you’ve followed the WMAP blog for some time, there is no lack of evidence how important salt marshes and other wetlands are. Here, I will dive deeper on salt marsh ecology with a focus on the low marsh zone. First, here are some important fast facts on salt marshes.

These characteristics make the marsh a stressful environment for both plants and animals that live there.

Typical salt marshes can be split into two zones, best classified by the types of vegetation growing there. The vegetation zonation is driven by the conditions the plants are exposed to. Being flooded periodically with salty water means the plants in the low marsh zone are best adapted to dealing with that stressor. Plants in the high marsh zone are less frequently flooded but they still have special adaptations to deal with the periodic salty-water interactions. Plants in the high marsh are more diverse than the low marsh because there is less stress.

Let’s take a further look into the low marsh community and meet the three major contenders that work together to help the low marsh thrive.

First up is the dominant low marsh grass – Sporobolus alterniflorus (previously Spartina alterniflora) or Saltmarsh Cordgrass.

Saltmarsh Cordgrass is the best suited grass for life in the low marsh because it can handle all the stress that comes with living on the water’s edge. It has a special adaptation to excrete salt on its leaves that it takes up from the water, leaving it with a little sparkle. Saltmarsh Cordgrass has shallow roots that can thrive in the low oxygen environment of the mud.

Give it up for Saltmarsh Cordgrass!

Next up are Ribbed Mussels (Guekensia demissa).

These mussels can be found in the low marsh at the base of Saltmarsh Cordgrass along the tidal channel. They form large clumps together, using special threads to anchor them in place. They are filter feeders, opening their shells slightly when submerged at high tide to allow water to pass through. At low tide, they close shut to avoid drying out until the next high tide.

Give it up for Ribbed Mussels!

Last up are Fiddler Crabs (Uca sp.)

Fiddler crabs are named as so because the males have a large single claw that moves in a “fiddle-playing motion” when trying to find a female mate. It is easy to spot the difference between males and females because the females have two small claws compared to the males one large and one small claw.

At low tide Fiddler crabs can be seen alongside their burrows in the mud. The burrows are their homes and can be up to two feet deep. During high tide the crabs will plug-up their burrow with mud, so they do not get flooded.

Give it up for Fiddler Crabs!

These three contenders are important for marsh function, each playing an important role in low-marsh ecology.

Ribbed mussels provide structure for the roots of Saltmarsh Cordgrass, as well as fertilizer that aids the grass growth in the stressful environment. The sturdy structure created by mussels decreases erosion. Whereas Fiddler crabs aerate the sediments with their burrows, bringing oxygen deeper into the very-low oxygen mud to be utilized by the Saltmarsh Cordgrass. Also, fiddler crabs consume the dying plant matter, allowing them to recycle nutrients for use. The Saltmarsh Cordgrass provides the mussels with attachment sites and increases food supply by trapping sediments while also providing the Fiddler crabs protection from predation and a buffer from other physical stressors.

But like all things, balance is important.

Too much or too little of something can throw things off. While coastal wetlands like salt marshes are facing challenges due to climate change and sea-level rise, shifts can occur. One example researchers have observed is a decline in predators (such as fish and wading birds) leads to an increase in Fiddler crabs. The abundance of Fiddler crabs means an increase in their burrows, which can weaken the marsh banks and lead to collapse. The three contenders working together in harmony are what helps a Saltmarsh thrive. We therefore must appreciate how dynamic the natural world is and consider the constant changes that occur around us each day.