Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: May 15th, 2019 in Education and Outreach

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

In our Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program we speak so often about the ecosystem services that wetlands provide or the beneficial functions wetlands perform daily. We rattle them off in varying order “provide vital habitat for plants and wildlife, improve water quality, protect our coasts, act like a sponge to store floodwater, sequester Carbon from the atmosphere”.

We do this so often, that sometimes we forget to take a step back and explain what exactly we mean and how exactly wetlands work. For example, how can a wetland clean water?? Wetlands are muddy and sometimes stinky. How on earth could a wetland clean my water?

Wetlands are magicians. In their own, natural, wonderful form, they magically filter out and pull aside an assortment of nasty stuff that you and I don’t want in our streams, bay and ocean, or as we kayak and fish.

What can wetlands help filter out from our waters, you might ask?

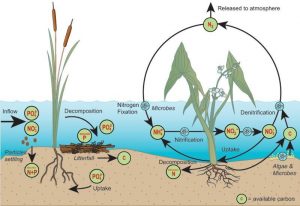

A magician rarely reveals their secrets, but in this case we’re spilling the beans. Wetlands remove nutrients through a combination of complex physical and biological processes. Let’s break it down (pun intended)..

Wetlands are like sponges and are great areas for holding onto water. They are also areas where the speed of water flow is drastically reduced and sometimes even stands still. As the water sits in the wetland, nutrients can be removed from the water in a couple of ways: they can simply sink down and settle on the soil surface, be released into the atmosphere or be trapped in the soil as the water filters its way slowly down through the ground.

As you can see, soils play an important role in this physical process. One of our favorite marsh metaphors to use in presentations is that wetland soils are like a strainer or sieve. We hold up a pasta strainer and kids look at us like we’re crazy but really, it fits. Just like the strainer, wetland soils have lots of tiny holes, nooks and crannies (think English muffin) to trap impurities and toxins. This process allows the cleaner water to continue on through, entering the stream or bay or even our underground aquifers.

There are also biological processes occurring in wetlands that can help to clean our waters. Plants, algae, and bacteria can use and transform nutrients that have sunk onto and in the soil to grow big and strong and create future generations.

Bacteria (or microbes) are really neat organisms that do some fancy biogeochemical processes called nutrient transformations. Ammonification, nitrification and denitrification are examples of nutrient transformations that turn not-so-great chemicals into less harmful ones or into a useful nutrient for plants. All of these processes are facilitated in many places throughout a wetland.

Healthy microbes also need a good source of carbon for their growth and energy and wetland plants serve as a key source of carbon! So the take home message is that these bacteria rely on wetland plants, and a wetland planted with lots of native plants (as opposed to an open pond) is going to be capable of the most nutrient transformation.

If you’re thinking that this is interesting but doesn’t affect me, you might be surprised to learn that approximately 25% of the State of Delaware is made up of wetlands, and that from where you are reading this right now, there is probably a wetland within a mile of you. This means that a wetland is hard at work for you right now trying to keep up with all the demands we place on them.

There are a few things you can do to lighten their load, so to speak.

Let the magician put on a show uninterrupted and we can all enjoy cleaner, healthier waters!

Written on: May 14th, 2019 in Wetland Animals

By Clare Sevcik, DNREC’s Nonpoint Source Program

There are so many charismatic animals that make Delaware waterways their home. Most people living in Delaware can easily recognize a few of the most popular species: bald eagles, osprey, blue crabs, horseshoe crabs, beavers, river otters, and many more. But there are many more animals living below the water’s surface that are incredibly important to the area’s ecology. One of these lesser known animals are the freshwater mussels.

Freshwater mussels are bivalve mollusks that live along the bottom of rivers, streams, and lakes in softer substrates like sand. They can live for a very long time and, in a healthy environment, some species can live to be 100 years old!

North America is also home to the most species of freshwater mussels in the world. Around 300 species live here. Worldwide, there are about 1,000 species. So, we are home to almost 1/3 of the world’s species. Most of those are found east of the Mississippi River, too.

Freshwater mussels have an unusual life cycle. Before they settle and become the slow-moving bottom dwellers we all picture, they are very mobile and hitch rides on the gills of various fish. For the first portion of their lives, they’re parasites.

Female mussels internally fertilize their eggs with the sperm of nearby males. Once fertilized, she releases the larvae (called glochidia) as migrating fish pass by. The glochidia are attached to the fish’s gills until they are large enough to survive on the stream bottom, which may be far away from their parents since fish can travel great distances and against currents. Mussels depend on these fish and each mussel species relies on different fish species to host their young.

Interestingly, freshwater mussels aren’t eaten by humans, like their saltwater relatives. Native Americans used to supplement their diets with mussels, but nowadays we have many more protein options. Freshwater mussels aren’t as tasty as their saltwater counterparts and can often be full of pollutants and/or parasites that have bioaccumulated over their lifetime of filter feeding.

Most species are also classified as endangered or threatened and cannot be collected. Instead, they are eaten by raccoons, muskrats, river otters, fish, and turtles. But they serve a much more important ecological function than just being food.

Mussels are incredibly efficient water filters! A single mussel can filter through approximately 20 gallons of water per day. Why do they filter so much water? Mussels are filter feeders and comb the water for food, such as algae, bacteria, and small, microscopic plankton. While doing so, they reduce the amount of sediment and other nutrients in the water.

Even though they are such productive water filters, freshwater mussels are very sensitive to the quality of their environment. They cannot survive in waters that are heavily polluted or in areas with erosion and sedimentation issues. Thus, mussels are more likely to be found in cleaner waterways that are not overwhelmed by pollution, runoff, or erosion.

Their sensitivity to water quality also makes them great bioindicator species, as they can only survive in healthier waters. A bioindicator species can tell researchers how healthy a waterway is based on their presence or absence.

Due to many factors, freshwater mussel populations have been declining, and approximately 70-80% of North American species are considered endangered. They are threatened by poor water quality and reduced access to their fish hosts. Dams prevent fish from traveling upstream, so some mussel populations have been effectively cut off since without hosts young mussels wouldn’t be able to survive in the water column.

But even if their hosts are available, the areas suitable for mussel survival are scarce. So once they detach from the host’s gills, they can’t survive in those areas. Mussels have also been affected by invasive species, such as zebra mussels and Asian clams. These invasives tend to reproduce quickly and overpower local mussel populations.

A LOT! Various nonprofit organizations and state agencies, such as our program within DNREC, have been actively trying to monitor mussel populations and improve local water quality.

The Partnership for the Delaware Estuary (PDE) has an extensive program in place to try to monitor and restore native mussel populations to the Delaware River, Susquehanna River, and their tributaries. PDE plans to open a freshwater mussel hatchery in southwest Philadelphia in 2023. The hatchery aims to produce 500,000 mussels per year to reestablish populations.

Additionally, dams in Delaware are slowly being removed and allowing fish to freely migrate through waterways, which will reconnect isolated populations and introduce glochidia to new areas.

Even with all of those programs and actions in place, native freshwater mussel populations will take a long time to recover, especially species that grow slowly. So we have to try to expedite their recovery by improving water quality as soon as possible!

There are many things you can do, regardless of where you live, to improve local water quality. Reducing fertilizer use, installing rain gardens and buffers, and even picking up trash can help reduce water pollution. For more information on how you can help improve local water quality, check out the Delaware Watersheds and Livable Lawns websites!

Written on: May 14th, 2019 in Wetland Assessments

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

In 1998 the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control’s (DNREC) Environmental Scientist, Amy Jacobs (now with The Nature Conservancy), took part in a grant project held by the Delaware chapter of The Nature Conservancy and the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. This project developed the science and comprehensive hydrogeomorphic models for freshwater wetlands in the Nanticoke River watershed and assessed water quality benefits of wetlands in varying condition. This was done to develop a wetland profile for wetlands in that watershed.

Then, in 1999 DNREC addressed the need to track not only the acreage of wetlands across Delaware and how that acreage is changing over time, but also examine the on-the-ground condition of wetlands. Measuring wetland condition compared to reference condition (the best and healthiest wetland you can find) gives a measure of how well wetlands are able to perform their natural functions and benefits.

Are our wetlands capable of trapping carbon, of intercepting and filtering pollutants from our surface waters, of holding stormwater and preventing flooding? These free benefits were underappreciated and not well tracked. If we can rate and track wetland condition as it relates to wetland function, we can grasp where wetlands are thriving and where they need work. Thus began the mission of the Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program (WMAP)!

Since then we have been building and growing! Our program has (with some partner collaboration) created 4 standardized wetland assessment protocols that rate wetland health, function and features. Working watershed by watershed we have visited nearly every corner of Delaware on the ground (12 watersheds).

This summer we will be working in the Brandywine Creek watershed which leaves only the small Pocomoke River still to visit. Over that time we have visited and assessed 1,420 random wetland sites across the state. With the help of willing landowners we have been able to access public and privately owned wetlands, allowing us to accurately rate wetland health statewide.

Along the way we met and worked with roughly 20 young professionals who joined us as seasonal wetland field technicians, assisting us during the busy summer season. Fieldwork is an adventure for everyone involved and we enjoy making memories and sharing our passion for wetland science with young minds.

It is so exciting the see how the Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program has grown over the years. Growing out of a research study with The Nature Conservancy, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, and Environmental Protection Agency, the program has held firm to using science as their foundation to improve management and educate a wide diversity of audiences. – Amy Jacobs, The Nature Conservancy, reflecting on where the program started two decades ago

Because unused data is wasted data we try our best to share our work and our information with the widest audience possible through every means we can. Over 20 years we have amassed thousands of photos, thousands of points of data and the most comprehensive tidal and non-tidal wetland condition dataset in the Mid-Atlantic Region.

Over the years we have gotten better at communicating wetland science and findings to an audience that isn’t always wetlands savvy. We’ve asked, we’ve survey and we’ve listened to what is important to Delawareans and how we can inform them to improve wetland protection and conservation.

Our program has been extremely fortunate to receive funding that allows us to continually grow and develop our program, addressing new needs as they arise. In 2008 we added a team member to focus on outreach and education which enables us to share our projects and results with many audiences online and in-person. We continue to expand our audience every year and we now average 3,500 in-person interactions per year through presentations, workshops, and exhibiting at events.

As times change so have we to reach a wider audience. In 2011 we established a Delaware Wetlands Facebook page which has accrued 2,000 followers. In 2014 we started an Instagram account which now has 1,200 followers who get to enjoy pictures of our adventures and mishaps in the field. Additionally we decided to start making short educational videos, which are great for anyone teaching about wetlands. This really pushed us out of our comfort zone! We have now starred in 14 videos which have 44,000 views.

Over the course of our program our staff has given approximately 275 professional presentations to audiences around the country (and internationally too!).

But we didn’t stop at attending and presenting at conferences. We decided to convene wetland professionals of all types from around the state and eventually around the region for a Delaware Wetlands Conference. Held for the first time in October 2001 at Cape Henlopen State Park, the agenda focused on wetland status in Delaware, wildlife and habitat management, monitoring, restoration and permitting.

Over the years the conference moved to the Dover Sheraton Hotel to the Dover Downs and now the Chase Center on the Riverfront in Wilmington. What started as a one-day gathering of 100 has expanded to a two-day event for 350.

With 8 conferences on the books we are still striving to make the conference worthwhile and effective. Although it requires a year of planning, hosting the Delaware Wetlands Conference is extremely rewarding. To see so many sectors of professionals gathered together with a common interest in wetlands and a desire to learn and collaborate is inspiring. We look forward to the 2020 conference already!

We’ve accomplished a lot for such a small program, but we still have a lot to do. Another early member of the program Chris Bason, Executive Director for the Delaware Center for the Inland Bays gives the program kudos for its accomplishments but questions if the resulting scientific information is being heeded.

Wetland science in Delaware is very strong thanks in large part to the WMAP and the EPA’s and State’s continued investment in the Program… The question on the minds of those that have worked so hard to understand the importance and condition of these extraordinary natural resources remains: will Delaware’s political leadership be moved by the 20 years of science indicating these wetlands need protection? – Chris Bason, Delaware Center for the Inland Bays

For now we will focus on gathering relevant information and sharing our work with familiar and new audiences alike. For example, we are focusing on providing realtors and homebuyers with important information and tools to navigate buying and owning wetlands.

In addition, in 2019 we will be releasing 10-year updated statewide wetland maps and examining how and where wetland acres have changed in a decade.

Every year we continue to set higher goals for our program to reach a wider audience, interact with more citizens, tackle new issues, and push our limits in the name of wetland science and wetland conservation. Remember, you can find us on this blog, our social media accounts above, or main website anytime of day for wetland fun facts, photos, wetland research and data. See you around!

Written on: May 8th, 2019 in Wetland Animals

By Erin Dorset, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Birding is always exciting in Delaware. While some bird species are year-round residents, many others are migrants traveling along the Atlantic Flyway. This keeps things interesting, as it allows birders to see a very wide variety of species throughout the year. A lot of these awesome birds exist in or near wetlands in Delaware, which makes wetland habitats great places to go birding!

Here are some of the best sites to see birds in wetlands in Delaware (though this is not an all-inclusive list). For each place, we describe location, wetland habitat types, and how to get around. This will hopefully help you find the best locations that suite your birding interests!

Location: Smyrna

Wetland habitat types: tidal marshes, impoundments, mudflats

Description: This large refuge is probably the most well-known birding spot in the state. While there are some short walking trails and some observation towers at Bombay Hook, most of the refuge can be explored along a 12-mile driving loop. There are many places to pull off of the driving loop to look for birds in the wetlands.

Additional info: Click here to learn more about birding at Bombay Hook and see the map of the refuge. Also, view the refuge bird checklist for more details about what time of year you are likely to see different species.

Location: Milton

Wetland habitat types: tidal marshes, impoundments, mudflats, forested wetlands

Description: Prime Hook is another large federal refuge that can be explored on walking trails, by driving, or by a canoe trail. It is the site of a large restoration project that was designed to rebuild degraded tidal wetlands, which means that birds should benefit from the project!

Additional info: Check out the refuge map. Also see the bird checklist for more details about what time of year you are likely to see different species.

Location: Dover

Wetland habitat types: tidal marshes, impoundments, mudflats

Description: This is a state wildlife area that is made up of several tracts of land.

There are several parking lots and boat ramps, most of which require you to have a Conservation Access Pass (CAP). While there aren’t any designated walking trails, you can stop along roadsides, or view birds from a boat or a wildlife viewing tower. Note that hunting is permitted here.

Additional info: Check out the map of the wildlife area.

Location: Lewes

Wetland habitat types: tidal marshes, impoundments, mudflats, forested wetlands

Description: This state park has many hiking and walking/biking trails throughout many habitat types. Some go through maritime forest and dunes, and others pass by tidal marshes and a large impoundment (Gordons Pond). There is also a nature center at Cape Henlopen, where you can watch a live osprey camera! Plus, volunteers can participate in a hawk watch every spring and fall here.

Additional info: Look at the map of the state park, and check out the park’s birding checklist.

Location: Townsend

Wetland habitat types: forested wetlands

Description: Blackbird State Forest is quite large; it is made up of 9 tracts of land with about 40 miles of trails. This means there are great opportunities to find birds in and around the forest’s freshwater wetlands! Be aware that hunting is permitted within the forest.

Additional info: See the maps of the state forest tracts

Location: Bear

Wetland habitat types: forested wetlands

Description: The Swamp Forest trail goes around Lums Pond and through patches of forested wetlands for over 6 miles, providing a great opportunity to see birds that are associated with wooded wetlands! There are also several other trails and a nature center to enjoy.

Additional info: View the map of the state park

Location: Frankford

Wetland habitat types: tidal marshes, mudflats, impoundments, forested wetlands

Description: This is a state wildlife area that is made up of several tracts of land.

It has several parking lots and boat ramps, most of which require you to have a Conservation Access Pass (CAP). While there aren’t any designated walking trails, you can stop along roadsides, or participate in the auto tour. You can also view birds from a boat or a wildlife viewing tower. Note that hunting is permitted here.

Additional info: See maps of the wildlife area tracts

To learn about some more great birding locations in Delaware, including places with non-wetland habitats, see the Delaware Birding Trail.

While these are not all-inclusive lists—and some birds may cross over from one habitat type to another– here are some of the bird species that you might encounter in different wetland habitats in Delaware.

Clapper rail; Virginia rail; Marsh wren; Seaside sparrow; Saltmarsh sparrow; Great blue heron; Snowy egret; Great egret; Willet; Least bittern; Northern harrier; Osprey; Common moorhen; Sora; Glossy ibis; Forster’s tern

Semipalmated sandpiper; Least sandpiper; Sanderling; Semipalmated plover; Greater yellowlegs; Lesser yellowlegs; Black-necked stilt; Ruddy turnstone; Dunlin; Short-billed dowitcher; Red knot; Willet

Mallard; Northern shoveler; Green-winged teal; Blue-winged teal; Northern pintail; Gadwall; Bufflehead; Canada goose; Tundra swan; Snow goose; American black duck; Ruddy duck; Black-crowned night heron; Yellow-crowned night heron; Green heron; Great blue heron; Common moorhen; Least bittern; Red-winged blackbird; American avocet

Wood duck; Cerulean warbler; Louisiana waterthrush; Warbling vireo; Yellow-throated vireo; Prothonotary warbler; Kentucky warbler; Yellow-throated warbler; Barred owl; Eastern screech owl; Great-horned owl; Wood thrush; Northern flicker; Downy woodpecker; Red-bellied woodpecker; American woodcock