Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: March 17th, 2022 in Wetland Animals

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Early on a rainy but relatively warm February morning, while most people were still snuggled under the blankets, two biologists from DNREC Fish & Wildlife wade through a wetland pond in Blackbird State Forest. Their chest waders and raincoat keep them dry. Their headlamp helps them navigate in the early light around stumps and shrubs as they shuffle around the pond checking traps set the evening before. What are they after? The Eastern tiger salamander, one of Delaware’s rarest amphibians.

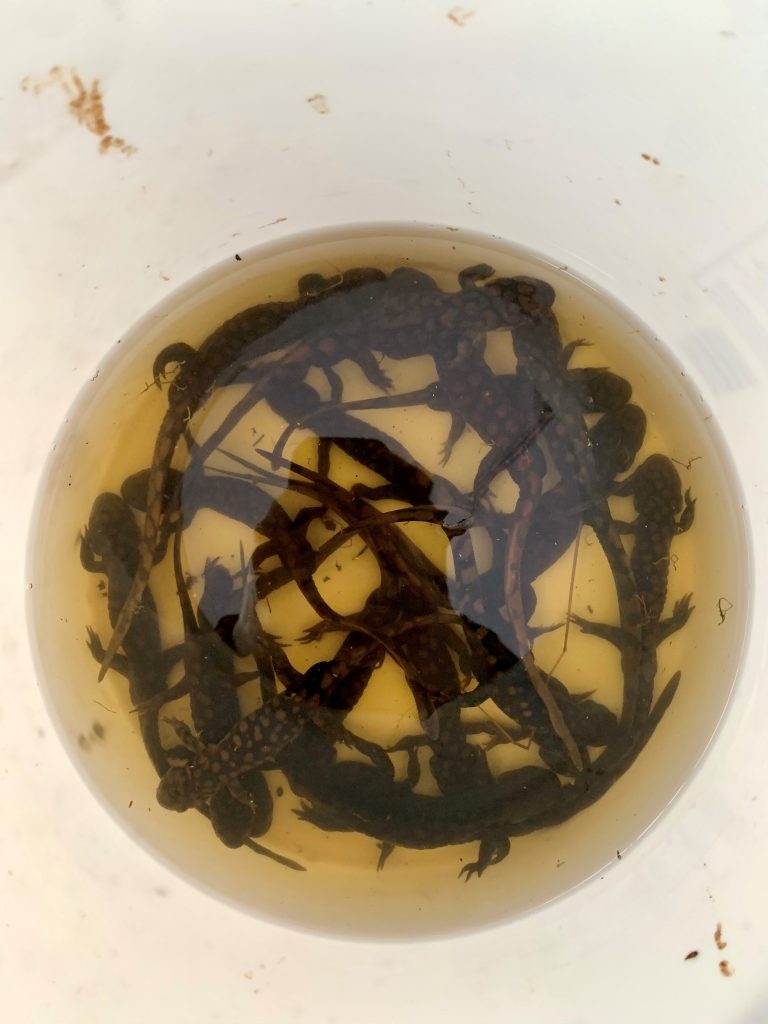

Today’s catch has been good, 100 individuals captured in this one large pond. There are several other ponds to check, yielding several hundred in total for the day. I pull up to the forest area parking lot hours later, well-rested, caffeinated, and ready to help with the detailed process of measuring and recording data on each salamander before releasing them. Life history data such as sex, length and egg bearing-status are recorded for each creature. A photo is taken as well, to be sorted and matched up with photos from previous years- a tedious task that helps biologists identify individuals by their markings.

All of this information is used to help DNREC count and track local populations of this state endangered amphibian. Timing is critical. Tiger salamanders are the first species to come out of winter brumation (that’s hibernation for cold-blooded species) in nearby forests to gather in vernal ponds to breed and lay egg masses. Their internal clock is motivated by warm rain in late winter to early spring. They may only hang out in ponds to breed for one or two weeks before heading back to upland forested habitat.

Tiger salamanders historically ranged from southern New York to northern Florida, but is now endangered in New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, is essential gone from Pennsylvania, and are of special concern in North and South Carolina. Their number one threat is loss of habitat. Clearing forests and removal of forested buffers around seasonal ponds leaves them no where to go. Although seasonal ponds normally dry up at the end of the summer, droughts and shifts in normal rain patterns due to climate change also increase mortality.

What can you do? Plant more trees! If you own forested property, leave logs and downed trees in place- they make good salamander hiding places. If you own a seasonal pond, be sure to keep a wide forested buffer around them. Resist the urge to clear and mow up to the edge. Lastly, encourage the protection of freshwater wetlands and buffers statewide and by county.