Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube RSS Feed

Written on: December 1st, 2018 in Wetland Animals

by Kenny Smith, Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Wetlands provide many services to us, like purifying our water, flood protection, and wildlife habitat. The animals that live in our wetlands can provide ample opportunities for outdoor activities like bird watching, fishing, and hunting. Delaware’s typical hunting and trapping seasons start in September and concludes at the end of January. Some of these species are migrants and pass through our wetlands on their way to wintering or breeding grounds, but most of these species are year round residents.

Continue on to learn about some of the hunting and trapping that you can do in the wetlands of Delaware and potentially partake if these opportunities seem interesting to you.

From left to right, top to bottom: Mallard, Canada Goose, Snow Goose, Brant, Pintail, Green-winged Teal Photo Credit: Audubon

Starting with the most common hunting activity in our wetlands is waterfowl hunting, this consists of ducks, Canada geese, snow geese, and brant. These species use a diverse array of wetlands in the state from tidal wetlands to wooded depression wetlands. Wood ducks prefer non tidal wooded wetlands where they can nest in tree cavities, while snow geese will roost along tidal wetlands on their way to wintering areas.

Most of the waterfowl hunting in Delaware is focused on the winter migrations of these birds, they leave the arctic breeding grounds and fly through Delaware on the way to wintering grounds in the southern U.S.

Based on Delaware Fish and Wildlife mail surveys, the estimated harvest of ducks last year was just over 40,000 while Canada geese harvest was about 20,000, and snow geese was 11,000. This survey estimates that around 5,000 people enjoy waterfowl hunting in the states wetlands every year.

Muskrat are a year round resident of tidal salt marshes throughout the state, they create small mounds in salt marshes where they live. Muskrat are members of the rodent family but are actually omnivores and will consume vegetation but also frogs and fish.

They are one of the more common species to be trapped in Delaware and have been a Delaware tradition since colonization, with the meat and fur being the objective. The furs are sought after for clothing manufacturing, mostly in China, Russia, and Korea now that the North American fur demand has decreased significantly.

The meat from muskrat is a local delicacy and is often sold to local restaurants, local wild game dinners, or consumed by the trapper. If you are daring, some Delaware restaurants still serve muskrat and it can still be found at local butcher shops.

The non-waterfowl gamebirds I am referring to are the rails, snipe, coot, and the gallinules and moorhens. Most of these birds migrate through Delaware, with rails being the exception being year round residents.

Rails are a secretive marsh bird that inhabits our tidal salt marshes, with 4 different species being the target of sportsmen. The clapper rail is the most common rail found in Delaware, with the sora, the Virginia rail, and the King rail being the least common. Snipe are the next bird that hunters can target, and this is not a childhood prank. Snipe are actually a very common bird that hunters pursue. These birds usually can be found around open marshes and mud flats of our coastal wetlands. In the Delaware Fish and Wildlife mail surveys, they estimated that almost 400 rail and about 40 snipe were hunted last year.

Coots, gallinules, and moorhens are not as regional hunted as they are in other parts of the country but we do have them and they legally can be harvested. Coots can be found along marsh edges and can create large flocks on open water while moorhens and gallinules are more solitary and can be found along edges of marshes or ponds similar to rails.

Bullfrog and Snapping turtles are year round residents and can be found in many of our freshwater wetlands throughout the state. Bullfrog hunting is slightly different from any other hunting that happens in wetlands, you are allowed to do it at night, you don’t use a trap or gun, and the frog season runs from May 1st to September 30th. Instead you can use a light at night in the warmer months and hunt frogs with a spear or gig. Bullfrog hunting is very common in the southern U.S., and is still practiced by many in the Delmarva region. Bullfrog hunting can be a very inexpensive hunting endeavor since only a light and gig are required once you have the proper license.

On the flip side snapping turtle trapping is a very labor intensive adventure and you will need a lot more equipment. You can still try and use a spear, gig, or net but it is usually not as successful as using traps. The snapping turtle season runs from June 15th to May 15th and each turtle has to be a minimum of 11 inches on the curvature of the top shell. Bullfrog and snapping turtle are the 2 most common herpetological prey for hunters to pursue and are abundant throughout the state.

Highlighted were just some of the opportunities to hunt or trap in the wetlands of Delaware, check the Delaware Hunting guide for the proper seasons and laws before partaking in these activities. You will need to purchase a hunting or trapping license and tag along with a friend or family member and enjoy the outdoors. Below are some online resources to help you if you would like to try hunting or trapping in Delaware.

Written on: December 1st, 2018 in Wetland Animals

by Erin Dorset, Wetland Monitoring & Assessment Program

In the spring and summertime, Delaware’s wetlands are teeming with wildlife. Frogs and toads are heard in chorus, calling for mates; turtles are observed slowly walking through the woods or basking on logs and rocks in the water; snakes are seen slithering across mosses or trees. But by late fall, many of these fascinating creatures seemingly disappear, making winter wetlands seem relatively quiet and still. Have you ever wondered where the reptiles and amphibians go when the days get short and cold, and how they survive freezing temperatures?

In the winter, many of these wetland animals undergo a process known as brumation. During brumation, animals will substantially lower their heart rates, activity levels, body temperatures, and metabolisms. Because their energy demands become so low in this state, they do not eat and barely breathe at all! However, some animals in brumation may still show some movement, particularly during warmer spells. This is why they are said to brumate, not hibernate, as hibernating animals typically do not wake or move around in the middle of their sleeping period. The place where they spend the winter is called a hibernaculum.

Many of these wetland creatures handle brumation a bit differently—read on to find out more!

Delaware’s wetlands are home to many aquatic turtles, such as the Northern diamond-backed terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin terrapin) and the Eastern painted turtle (Chrysemys picta picta), as well as many terrestrial turtles, such as the Eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina carolina) and the spotted turtle (Clemmys guttata). As winter approaches, aquatic turtles usually bury themselves in mud or under banks of water bodies to brumate, while terrestrial turtles typically go underground in burrows.

Hatchlings of some species may spend the winter within the nest where they were born. Because they are often under water or fully buried, they are unable to get a lot of oxygen. The oxygen the turtles do need comes from the few breaths they do take as well as from stored energy within their bodies. Unfortunately, this breakdown of stored energy without much oxygen can create harmful compounds within the body, such as lactic acid. Some turtles, though, such as Eastern painted turtles, have the really cool ability to neutralize the acid using the calcium carbonate in their shells¹!

Because turtles usually bury themselves, they are often able to escape contact with snow and ice. However, sometimes ice crystals can form in their overwintering spaces, creating a heightened risk of freezing. Turtles have an awesome way of dealing with this. Some species, such as the diamond-backed terrapin, are freeze-tolerant, meaning that they can still live for a certain amount of time even if some of their body fluids have frozen.

Other species use a strategy known as supercooling, where body fluids remain unfrozen up to a certain point even when the temperature has dropped below the freezing point². Once the days start to get longer and the temperature is consistently higher, the light and warmth act like biological alarm clocks; the turtles will know that spring has sprung and that it’s time to come out.

Much like turtles, frog species that spend a lot of their time in water, such as the Southern leopard frog (Rana sphenocephala utricularia) and the American bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana), will overwinter underwater. These frogs live off of extra energy stores within their bodies that they built up specifically for the winter months.

However, unlike turtles, frogs cannot bury themselves completely under the mud; rather, they can only bury themselves partially. With their skin exposed above mud, frogs can often get all of the oxygen they need to survive the winter through their skin!

When dissolved oxygen levels in the water drop, overwintering frogs are faced with a serious challenge, as they cannot survive more than a few days without the right amount of oxygen present. If such a challenge occurs, some frogs have the capability of sensing it and can undergo what is called behavioral hypothermia. In other words, the frogs will actually move to colder water in order to further lower their metabolism, which ends up increasing the amount of oxygen in their blood to keep them alive longer. But, if there is plenty of oxygen in the water, the frogs can actually move to a nearby spot with relatively warmer water³.

Terrestrial or land loving frogs have a different strategy to deal with winter. They will find a damp area in underground burrows, under leaf litter, or in deep crevices to escape freezing temperatures and frost.

Some frog species may actually overwinter at shallower depths than others; species that do this, such as the wood frog (Rana sylvatica), can tolerate freezing. These frogs use high concentrations of glucose (simple sugar) as a sort of “antifreeze” in their organs to keep them alive while parts of their body become frozen. Because of this, they can stay alive even while partially frozen with no breathing or heartbeat4! Once temperatures warm up, their heartbeat and breathing return to normal.

Many different snake species can be found in and around Delaware’s wetlands, including the common ribbonsnake (Thamnophis sauritus sauritus), Eastern ratsnake (Elaphe alleghaniensis), Northern black racer (Coluber constrictor constrictor), and Eastern gartersnake (Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis).

To escape the cold, these snakes overwinter in sheltered places such as burrows, rock crevices, and wood piles. Interestingly, many snakes will brumate in the same place each year, and often, they are not alone. It is common for snakes to spend the winter in a hibernaculum with other snakes, either of the same species or multiple different species.

Although the snakes may move a bit and drink a little water, they mostly remain within the hibernaculum with a slowed heartbeat and metabolism and no food until the weather is consistently warmer. Within their hibernaculum, though, some snakes may move around to relatively warmer spots to help increase their body temperature5.

¹Jackson, D. C. 2000. Living without oxygen: lessons from the freshwater turtle. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A, 125: 299-315.

²Baker, P. J., Costanzo, J. P., Herlands, R., Wood, R. C., and R. E. Lee, Jr. 2006. Inoculative freezing promotes winter survival in hatchling diamondback terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 84: 116-124.

³Tattersall, G. J. and G. R. Ultsch. 2008. Physiological Ecology of Aquatic Overwintering in Ranid Frogs. Biological Reviews, 83: 119-140.

4Storey, K. B. and J. M. Storey. 1984. Biochemical adaptation for freezing tolerance in the wood frog, Rana sylvatica. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 155: 29-36.

5Macartney, J. M., Larsen, K. W., and P. T. Gregory. 1989. Body temperatures and movements of hibernating snakes (Crotalus and Thamnophis) and thermal gradients of natural hibernacula. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 67: 108-114.

Written on: December 1st, 2018 in Wetland Animals

Guest Writer: William Koth, Delaware State Parks

Bryozoans may be one of our most overlooked and underappreciated animals. Known as “Moss Animals,” bryozoans are small, simple animals rarely growing more than 1/25th of an inch in length. However, most bryozoans form colonies that can vary greatly in number, form, and size.

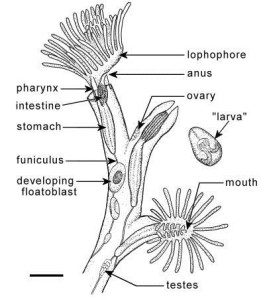

Each individual animal, or zooid, has a simple body style, usually round or oval in shape with a single opening that serves as both a mouth and an anus. Bryozoans lack any respiratory, excretory,or circulatory systems, but have a central nerve ganglion that allows the animal to respond to stimuli. They feed using small tiny ciliated (hair-like) tentacles that the surround the opening and push food through the it into the gut. In some species, and during certain life periods, these tentacles can be used for simple movement. Most species, however, spend the majority or all of their lifespan immobile.

The vast majority of Bryozoan species are marine animals. Of nearly 5,000 species, less than 90 have been identified in freshwater environments, and only 24 freshwater species in North America (so far).

The green circle highlights a rosette or colony of bryozoans. Photo credit: Leslie J. Mehrhoff (bugwood.org)

In the freshwaters of Delaware, you are most likely to encounter the native Magnificent Bryozoan (Pectinatella magnifica). This colonial species forms jelly-like “green blobs” on underwater vegetation, branches and other structures. They may also form free floating round colonies. The small visible rosettes on the surface of the colony are groups of 12-18 individual animals.

Although the Magnificent Bryozoan reproduces both sexually and asexually, the main way the colonies form is when the existing individual animal or zooid breaks away or buds asexually forming a twin. As they reproduce, they multiply into an ever growing sphere as the individuals point their mouths outwards to take advantage of available food. Meanwhile, the zooids excrete gelatinous material to give the sphere interior support.

Completely new colonies can also form asexually from small statoblasts (a group of cells encased in a hard covering to protect them from freezing or other harsh conditions). These statoblasts can float in the current, or settle to the bottom where they eventually grow into an individual zooid. These individual zooids can use their ciliated tentacles to move about in the water. They will eventually begin dividing and form a new colony. Smaller free floating colonies have been observed to use the ciliated tentacles in unison to move toward or away from stimuli.

Two bryozoan individuals and their anatomy. Dr. Timothy S. Wood (Department of biological sciences, Wright University)

The Magnificent Bryozoan actively feeds on suspended organic material, zooplankton, and algae. In this way it can be considered a filter feeder and may, in some instances, increase water clarity. Individual animals on the colony are clear or opaque. It is speculated that the green color of the colonies stems from ingested algae.

The Magnificent Bryozoan is native to Delaware, its native range extends from the Mississippi eastward to the Atlantic Coast from Ontario southward to Florida. Invasive outbreaks have been occurring in Europe since the 1930’s and west of the Mississippi since the 1950’s. The ecological impact of these invasions is still being studied, but colonies and groups of colonies have started to block some smaller waterways, ditches, and drainpipes. Colonies have been recorded up to 4 feet in Virginia, although the typical size found in Sussex County swamps, ponds and waterways is an inch to about a foot in diameter.

Encountering a colony of these animals can be a great experience. Trap Pond State Park staff receive several inquiries about these creatures each year. Most folks guess that they are some type of algae or fungus. Other guesses include freshwater jellyfish or fish eggs. Almost everyone is surprised to find out it is actually a colony of animals.

The staff recommend that you take full advantage of discovering one of these unique creatures. They do request that you not dislodge attached colonies, and not to keep them out of the water for more than a few minutes at a time. Lift it up, feel its surface, feel its weight, smell it. If you have a magnifying glass, take a look at the individual zooids on the surface. They are amazing animals that deserve a closer look and a little more appreciation!