Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: March 13th, 2024 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Research

By Caroline Kurtz and Beth Wasden, The Nanticoke Watershed Alliance

Let’s dive into a fantastic program out of the most biologically diverse watershed on Delmarva. But first, who are we! The Nanticoke Watershed Alliance (NWA) is a non-profit environmental organization that includes partners from Maryland and Delaware including representatives from industry, agriculture, environmental agencies, and businesses, as well as local, state, and federal governmental organizations. Our mission and goals are to foster partnerships and progress in conserving the natural, cultural, and recreational resources of the Nanticoke River watershed through dialogue, collaborative outreach, and education. We have multiple programs that our team works on with the community to better the health of the river. Events, publications, workshops, volunteers – you name it, we’ve got it. Some of these programs include Paddle the Nanticoke, Homeowner Workshops, Church Cost-Share Plantings, Residential Plantings, and our Nanticoke Creekwatchers Program. Be sure to sign-up for our mailing list to stay in the loop about volunteer opportunities and how to be involved with the NWA.

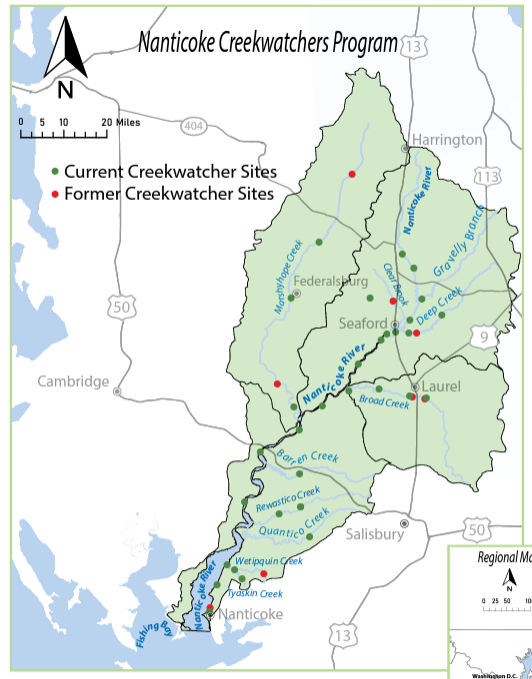

Now, back to the program mentioned. The Nanticoke Watershed Alliance’s Creekwatchers Citizen Monitoring Program began 17 years ago, in July of 2007. The program’s primary goal is to accumulate long-term, scientifically credible data to monitor the health of the Nanticoke River and the Fishing Bay headwaters. As the program developed and gained momentum, so did its outputs and reach. In 2017, the program obtained Tier 3 certification of its methodology, which means that data can be used for management and policy decisions by state and federal agencies. From the start of it all, we knew that the Creekwatchers program was ambitious. With over 725,000 acres, the Nanticoke and Fishing Bay watersheds encompass five counties in two states being Delaware and Maryland. The watershed even has over 25% of its land area made up of wetlands – critical ecosystems to both the natural works and humans alike. With understanding of the task at hand, we still wanted to transcend political boundaries and take the “watershed perspective” – after all, water does not know when it passes from one state to the next.

So, what exactly does a creekwatcher do? Our creekwatchers monitor 31 sites throughout the watershed every other week from late March through early November. We provide the equipment and the training and then our volunteers transform into a team of community scientists, going far and beyond the simple collection of a water sample to measuring much of the data themselves. Our creekwatchers look at water clarity, dissolved oxygen, salinity or conductivity, pH, and temperature. All of this is measured on-site with Secchi disk and other field instruments. Samples are also collected that our partner labs analyze for nutrients and chlorophyll a. Then our crew back at NWA takes it from there.

All the data and hard work that our creekwatchers do in the field allow us to have an in-depth understanding of the results and the river. The results help us evaluate trends and potential hazards to human health, the status of watershed health, and help our organization provide updates to the public on the river and watershed. A humble mention as well, our program’s quality assurance plan was the first to receive EPA approval in the Chesapeake Bay region. And since then, we have achieved Tier 3 under the Chesapeake Bay program via the Chesapeake Monitoring Cooperative.

This program really would not be what it is without our supportive partners (DNREC and the Chesapeake Monitoring Cooperative) and our fantastic volunteers. The volunteers have donated their time, skills, and passion to make our citizen monitoring program so successful. All of this hard work really shows in our annual Nanticoke River Report Card. Each season’s data helps us understand the present health of the river, while accumulated data allows us to identify potential trends and to create programs that target specific needs. We share our data with other organizations, government agencies, and members of the public. The 15-year report is available now and certainly worth a read.

The Nanticoke creekwatchers program is one of the key efforts of our organization. The work the participants do will help define the direction NWA goes in the future. We will be able to focus restoration activities, outreach events, and workshops based on the data our creekwatchers collect that will strengthen our impact and better the health of the Nanticoke River, the communities surrounding the river, and help us work toward our mission as well. Looking to find out more about the Nanticoke Watershed Alliance? Feel free to reach out to one of our staff members.

Written on: March 13th, 2024 in Natural Resources, Wetland Animals

By Alison Stouffer, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

It’s that time of year again where the days are getting longer, the weather is getting warmer, and life begins to return to our beloved wetlands. The sea of monotonous brown and gray will slowly make way for gorgeous greens, speckled with the purples, pinks, yellows, and whites of budding and blooming flowers. And with them, the prospect of pollination.

There are two methods by which pollination occurs in wetlands. First, is that of abiotic, or non-living, processes. For wetland vegetation, the primary form of abiotic pollination is that of wind pollination (also known as anemophily)1. The breeze that can be felt gently blowing across your face is the same force that can carry the pollen of one plant to another. While the dominant form of abiotic pollination, wetland plants are able to rely on more than just the wind to reproduce. Where there are wetlands, there is typically a source of water that can act as an additional vector of transportation for pollen1.

The second method by which pollination occurs in wetlands is that of biotic, or living, processes. This includes all the animals and insects that utilize the wetlands, intentionally or unintentionally picking up and dispersing pollen as they go about their lives. Despite a recent focus on threats to pollinator habitat, there remains a large gap in research surrounding pollinator use of wetlands and wetland-specific pollinators. However, we highlight here three insects that are known wetland pollinators.

Nude Yellow Loosestrife Bee (Macropis nuda)

For many, the word “pollinator” conjures images of plump bees buzzing around vibrantly colored flowers. This applies to wetland pollinators as well. While many bee species take advantage of wetland plants, the nude yellow loosestrife bee (Macropis nuda) is a wetland specialist. This bee species relies entirely on the floral oils and pollen of fringed loosestrife (Lysimachia ciliata), located in fringe wetlands of New England, for feeding their larvae and building nests2.

Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus)

Another common pollinator is the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus). This species of butterfly relies heavily on milkweed plants, including swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), to carry out its lifecycle, laying its eggs on the underside of milkweed leaves where they are afforded ample protection to grow into caterpillars3. While not the primary use of milkweed, adult monarch butterflies do consume the nectar of their flowers, helping to promote pollination.

In addition to swamp milkweed, monarch butterflies are frequent visitors of seaside goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens), commonly found in irregularly flooded salt marshes. Specifically, monarch butterflies rely on this wetland plant during fall migration as a critical source of nutrition4. As they feed, the butterflies pass pollen from one plant to another, making them important wetland pollinators.

Carrion Flies

Finally, and potentially one of the lesser-known wetland pollinators, are carrion flies. These flies are attracted to the smell of decaying and rotting flesh or dung where they are known to lay their eggs. While these insects might find joy in the ickier things in life, they still play an important role in pollinating wetland plants. One such plant is that of skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus), which boasts an unpleasant odor as the common name might suggest. This odor attracts carrion flies into the cupped area of the plant—known as the spathe—where they then pick up and deposit pollen from nearby plants5. Further, the mottled purple coloration of the plant and its unique heat-producing abilities create the perfect imitation of dead animal flesh and tissue5.

While these three insects discussed here have been linked to wetland specific plants, there exists a plethora of other pollinators that frequent these habitats. For example, generalist insect pollinators—insects that pollinate a wide variety of plants beyond wetland specific plants—have been known to visit wetland ecosystems for food resources. Further, there are species of birds and mammals that are known pollinators, such as hummingbirds and bats, which could be playing a role in wetland pollination. With pollinator diversity and abundance in decline partially due to habitat loss and fragmentation, it is crucial to protect and restore healthy ecosystems, such as wetlands, that can provide the necessary resources pollinators need to survive and thrive.

Written on: March 13th, 2024 in Education and Outreach

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Time is ticking when it comes to protecting and conserving our precious resources in Delaware. From the 90 miles of coastline to the forested areas on the western side of the state, all three counties have diverse habitats which provide a myriad of benefits free of charge to us humans. Today many Delawareans value wetlands and open space for their beauty, wildness, and many ecological benefits. To be sure these crucial habitats are not lost or degraded in the future, conservation efforts need to steadily continue. But not every citizen is “in-the-know” about the conservation efforts being encouraged by many organizations and government entities. So for this blog installment, we wanted to look at several of the victories in wetland and land conservation in Delaware to help spread the word.

Milford Neck Nature Preserve

On the southeastern edge of Kent County lies a nature preserve like no other. Milford Neck Nature Preserve is owned and managed by a combination of entities, as well as private individuals all working towards a greater cause. Wetland restoration being one of them! Tidal marsh, beach, coastal and upland forest, and agricultural lands make up the area, and the preserve itself is the only remaining forested area greater than 1,000 acres on the entire coast of Delaware. It also provides support for a wide variety of species and habitats, such as migratory waterfowl and spawning horseshoe crabs. The Milford Neck land holdings, including the areas owned by state of Delaware, Delaware Wild Lands, and The Nature Conservancy, form a block of 10,000 acres of protected land and nearly 10 miles of undeveloped bayshore that extends from the Mispillion River north to the Murderkill River. This significant land holding offers vital habitat preservation and is a noteworthy accomplishment of mosaic landscapes.

Greenly Property

A solid win for wetlands was the 98 acres purchased in February of 2022 to expand Killens Pond State Park and help protect the corridor between Killens Pond and Browns Branch. The forested wetlands on this property provide crucial habitat for the federally-listed endangered plant species Swamp Pink (Helonias bullata). As an obligate wetland species, it occurs along streams and seepage areas in freshwater swamps and other wetland habitats.

Expanding State Wildlife Areas

As a previously used Bird-a-thon location, the Cataldi Property is a lovely combination of forested wetlands, marsh, and wildflowers. This 166-acre area was purchased in August of 2022 by the Delaware Open Space Program and is located in northeastern Kent County. The acquisition expanded the Tony Florio Woodland Beach Wildlife Area near Smyrna with hopes that the forested wetlands, including freshwater ponds, will be successfully maintained.

In order to expand and connect the two tracts of the Eagles Nest Wildlife Area, four more acres of forested wetlands were acquired in New Castle County from the Duffy Property. As well as a another very recent addition that includes the Sandom Branch Tract. DNREC’s Conservation Access Pass is required to access Division of Fish and Wildlife areas such as these, and permitted hunting opportunities are available. Remember – hunting it an important part of habitat management and conservation.

Heading down south to the Shockley Property in Sussex County, this land acquisition added another 13 acres to the Assawoman Bay Wildlife Area. What is unique about this site is that the land was provided via donation, a major partnership win between the landowner and DNREC to protect tidal marshes in the Assawoman Bay. This over 3,000-acre wildlife area is a popular for raptor birds, boaters, woodpeckers, hunters, and is even home to a living shoreline!

Native Lands in Delaware

The state-recognized Nanticoke Indian Tribe and the Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware have long sought to reacquire some of their ancestral lands for education, agriculture, and traditional uses. These tribes called our region home for well over 10,000 years and practiced environmental stewardship before it was even thought of. For many decades, the Nanticoke Indian Tribe only owned 1-acre of ancestral land and had no other property for tribal functions. In 2021, when 31 acres adjacent to their historic land came up for sale, three entities came forward to assist the Tribe with acquiring the land. The state of Delaware’s Open Space Program, Mt. Cuba Center, and The Conservation Fund joined forces to restore property ownership to the tribe and created a conservation easement that protects it from future development. Most recently, in June of 2022, The Lenape Conservation Easement was established on 11 acres in Kent County to protect lands adjacent to Fork Branch Nature Preserve. In addition to the land donated, The Conservation Fund also donated the ownership rights to the Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware.

Who is Doing the Work

Many entities have their hands in the honey pot of these success stories and are making strides to continue conservation in Delaware. The Delaware Open Space Program plays a vital role in the acquisition and management of many of these natural and cultural areas. DNREC, the Delaware Forest Service, the Delaware Division of Historical and Cultural Affairs, and the Delaware Open Space Council are involved with the program and long-term success of said landscapes. Another notable player is The Nature Conservancy (mentioned previously), who have acquired and protected over 31,000 acres of land since 1990. In particular, their commitment to the Delaware Bayshore and wetlands helps spread the word on the importance of coastal protection and resiliency. The Delaware Nature Society is carefully managing habitats throughout the state with biodiversity in mind. Whether it be bird conservation or soil and food production, this non-profit is ensuring a thriving diversity of our land, plants, and animals. This list can go on!

Seeing the progress of conservation efforts made is a key step in better understanding how to continue it in the future. Sharing lessons learned, securing dedicated funding, researching management practices, providing outreach and education – all these play a part in how we will carefully maintain and upkeep Delaware’s natural and cultural resources to prevent them from disappearing. Our DNREC wetlands program is more than proud to not only see some of these extraordinary habitats or locations, but have a small hand in protecting them for citizens and nature alike. As Delawareans, you too can have an impact on how conservation continues in the first state. Purchase food from a regenerative farm, attend a local tribes annual Powwow, take a stroll in a nature preserve you’ve never been too, donate land or enroll in a conservation easement. What role will you play in it all?

“We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

– A Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold