Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: December 11th, 2024 in Education and Outreach, Natural Resources

By Jana Savini, Coastal Collaboration Coordinator, Partnership for the Delaware Estuary and RASCL Coordinator

The Delaware Resilient and Sustainable Communities League (RASCL) is a collaborative network of state agencies, nonprofits, and academic institutions that are dedicated to enhancing the resilience and sustainability of Delaware communities. By addressing climate challenges and capacity limitations, RASCL brings partners together, leverages limited resources, and coordinates efforts to empower local communities to implement effective, long-term resilience and sustainability initiatives.

RASCL serves as a hub for technical expertise and resources, uniting diverse partners under a shared vision of a resilient and sustainable Delaware. Through collaboration, RASCL addresses critical issues such as climate change, coastal resilience, sustainable land use planning, and resource management. Its outreach initiatives include free technical assistance, resource guides, information sharing, and community engagement, making RASCL a valuable resource for those navigating complex environmental challenges.

Who is RASCL?

The Resilient and Sustainable Communities League (RASCL) is an ad-hoc network of 28 member organizations. Its members represent diverse fields, including coastal resilience, natural resource management, energy, transportation, housing, emergency response, mental health, and outreach, among others. The network offers benefits beyond the capacity of individual organizations, such as programs tailored to support the practitioners, enhanced outreach efforts, and strategic networking opportunities. These efforts foster purposeful, mutually beneficial relationships that drive long-term success and sustained collaboration.

Key Initiatives

Project Guidance Group

The Project Guidance Group provides hands-on assistance to Delaware communities in planning and executing projects that enhance sustainability and resilience. Acting as a bridge between local communities and available resources, the group offers free technical support, information sharing, and connections to subject-matter experts. This collaborative approach ensures projects are effectively implemented and deliver lasting benefits to communities.

Developing a Community Sustainability Plan Resource Guide

To support local governments in creating sustainability plans, RASCL has developed a comprehensive guidance document. This resource serves as a framework for municipalities to craft strategies balancing environmental, social, and economic priorities. The guide emphasizes integrating sustainability and resilience, addressing potential climate impacts, and offering actionable steps. It is designed to be adaptable, empowering local leaders to tailor it to their unique needs and challenges.

Coffee Hours

RASCL Coffee Hours provide opportunities for information sharing and professional networking, fostering collaboration across diverse sectors. Held quarterly at various locations throughout the state, these events are offered both in-person and virtually to accommodate a wide audience. Each Coffee Hour features presentations that highlight best practices, emerging topics, innovative projects, funding opportunities, and more.

2025 RASCL Summit

RASCL’s Annual Summit is a cornerstone event that convenes professionals, community members, government agencies, and elected officials to address critical issues impacting Delawareans. Serving as a platform for knowledge sharing, collaboration, and innovation, the summit promotes a unified and proactive approach to community resilience and sustainability. Attendees can explore best practices, gain insights from successful projects, and engage with experts on pressing climate change challenges.

The 8th Annual RASCL Summit will take place on Wednesday, March 5, 2025, at the Del-One Conference Center in Dover, DE. Registration information is available on their webpage.

Collaborative Impact

RASCL’s success is rooted in its extensive network of member organizations and community partners. These partnerships ensure that RASCL’s initiatives are informed by cutting-edge research, diverse perspectives, and practical expertise. By leveraging these collaborative relationships, RASCL delivers innovative solutions that address the unique needs of Delaware’s communities.

For more information about RASCL’s programs and resources, be sure to browse their website. Ready to get involved and find out more? Sign up for their mailing list!

Written on: December 10th, 2024 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Animals

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Though pretending to be a National Geographic photographer is on our resumes, working in wetlands really does provide an exclusive opportunity to get up-close and personal with wildlife. Weather, soil, water, humans – many factors influence the presence of fauna in all wetland types. Each type of habitat can have specific, uniquely adapted species that call that wetland home, and some even exclusively depend on said wetland for their survival. As avid explorers of these ecosystems in Delaware, we’ve snapped some pretty interesting photos. Let’s browse through some of the weird and wonderous wildlife of wetlands.

Water Stick (Ranatra linearis)

At first glance, we thought this was plant debris until it moved. As an underwater predator, these insects not only camouflage well in their environments, but can ambush prey quickly. Water sticks adopt a mantis-like pose when submerged, capturing passing creatures like tadpoles, invertebrates, and small fish. This species uses its hooked front legs to catch food, while its tail acts like a snorkel above the water to siphon air for breathing. A crazy characteristic of this insect is that during hot summer days, adult water sticks often leave the pond to hunt in emergent vegetation or may fly to a new pond. Quite the journey for a small, slender bug.

Bryozoan

Meet this mysterious microscopic organism. A bryozoan, or zooid, grows no larger than 4 millimeters (5/32 of an inch) wide and forms colonies – like those pictured – that may contain thousands or millions of individual invertebrates. There are approximately 4,000 species in the phylum Bryozoa, and colonies come in many shapes and sizes. Species and colonies range from flat to folded, leaflike bushes to bouquets of sponges or flowers. Bryozoans lack any respiratory, excretory, or circulatory systems, but have a central nerve ganglion that allows them to respond to stimuli. As filter feeders, these creatures spend most of their life immobile, free floating or attaching to structures and vegetation underwater. Pretty neat for a big blob found in the Rehoboth Bay.

Eastern Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum)

Large and in charge. At up to 12 inches long, the Eastern tiger salamander is the largest salamander in Delaware and is listed as endangered by DNREC’s Division of Fish and Wildlife. This amphibian spends most of its life in burrows below the upland forests of the coastal plain where they feed on snails, worms, and insects. When ready to breed in early spring, they emerge from the forest to migrate to vernal pools, or Delmarva Bays, one of Delaware’s unique wetland communities. The salamanders depend on these non-tidal wetlands for survival, using the pools to lay eggs on submerged vegetation and as a safe space for larvae to mature. Time is of the essence when researching or tracking the population in Delaware, as these crawlers only stay up to two weeks in vernal pools before heading back to their upland forested habitat.

Piebald Deer

We were happy our wildlife cameras spotted this one! Often mistaken for albino, piebald deer are few and far between in populations, with less than 2% of white-tailed deer having the genetic mutation. This recessive trait mutation causes varying amounts of white hair with brown patches or mostly white hair with very little brown patches on the animal. Not only are piebald deer highly visible to predators, but they are also often born with physical abnormalities such as shortened legs, deformed hooves, or arched spines. Currently in some states there are hunting restrictions and laws against harvesting these deer for sport or management purposes. Historically speaking, some Native American and Indigenous tribes believed these deer were spiritual or sacred and therefore not be hunted or bad luck to kill. All in all, seeing a piebald deer is a rare and beautiful sight.

Hellgrammite (Corydalus cornutus)

Here is something you don’t see every day. Featured here in its larval stage, the hellgrammite or Dobson fly, takes two names for the two distinct life stages it lives. As a larva, the macro-invertebrate spends up to three years in freshwater under rocks in swift moving water, using thick filaments as gills for breathing. During this larval stage, the aquatic insect is equipped with an impressive set of pincers, or mandibles, to catch and eat their prey such as small fish, other aquatic insect larvae, and tadpoles. After years of aquatic life, the hellgrammite larva enters full metamorphosis to emerge into a winged Dobson fly, only to live for a few days. And don’t worry, the pincers did not get us this time…

Glass Eel (Anguilla rostrata)

This little thing can go a long way. The American eel is a migratory species that spawns in the open waters of the Atlantic Ocean but spends its adult life within inland waters along our coasts. Born in the Sargasso Sea between the Caribbean and Bermuda, the juvenile eels will drift in the open ocean for months or more until currents carry them inland towards the nearest estuary or river (termed catadromous). During the early stages of their life they will metamorphose into a glass eel, shown here, as currents assist with migration transport into estuaries. Named for their transparent, glass-like appearance these little 2-inch wonders will make their way upstream in the late winter and early spring in search of freshwater or brackish habitats to grow in.

We use the term “weird” lightly here, as more of a hook to get folks reading and engaged about wetland wildlife they might not ever encounter or known existed. One of the most impactful ways of sharing knowledge about nature is through photography. It can be a form of conservation, helping raise awareness about a particular species or habitat. It can be considered an art form, capturing the beauty of living things aiding in the understanding of our delicate ecosystems. Diving into the wonders of the natural world in this way doesn’t require more than a cell phone and taking a good look at your surroundings. Working in wetlands is no easy task, so taking a quick photo is nice break from the mud and sweat, but even more worthwhile knowing it’s not just for our own camera roll.

Written on: December 10th, 2024 in Natural Resources

By Alison Stouffer, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

The seasons are changing and while I wish we could stay in the warmth of the Southwest a little longer, our road trip will be taking us up north to the Midwest United States. For those of you joining us for the first time, we are slowly making our way across the country as we explore a new wetland in each state of the US. If you are feeling like you missed out, you can read up on the first and second excursions on our blog.

Falling between the Rocky and Appalachian Mountain ranges, this region of the country is characterized by low, flat, and rolling prairies. With wetlands covering over 50% of the region1, these states are known for the Great Lakes and their abundance of prairie potholes. Prairie potholes are non-tidal, freshwater, depressional wetlands created from historic glaciers that now provide essential habitat for migratory waterfowl2. We will explore these, and more, as we embark on our journey through the Midwest.

Kansas

Our first stop of the Midwest road trip takes us to central Kansas where we will be visiting the 41,000 acre wetland complex of Cheyenne Bottoms. Designated as a Wetland of International Importance, Cheyenne Bottoms is the largest freshwater marsh and inland wetland in the US! This wetland not only provides the public (us) with a great road trip stop but is also an important stopover for migratory birds along the Central Flyway.

Nebraska

A day’s drive north and we come to Agate Fossil Beds National Monument. At first glance, our destination seems to be dominated by prairie grasslands; however, the Niobrara River feeds a handful of wetland habitats. Within the river floodplain, you will find riparian areas, oxbow ponds, ephemeral streams, seeps, and springs. Due to the flat terrain, the river is often changing directions and meandering throughout the plains creating an ever-changing environment of wetland habitat.

South Dakota

Continuing north, we will be stopping next in South Dakota. Sand Lake National Wildlife Refuge encompasses an 11,450-acre prairie pothole lake, designated as a Wetland of International Importance. Managed by the US Fish & Wildlife Service, this refuge offers visitors a variety of activities including, hunting, wildlife viewing, birding, and hiking. If we are lucky, we may even see refuge scientists conducting vegetation and wildlife surveys to monitor wetland health!

North Dakota

Continuing our journey through the heart of the prairie pothole region, we will be visiting Tewaukon National Wildlife Refuge for our North Dakota wetland. This refuge is recognized for its importance to the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate Tribe. Providing a bountiful location for native people to hunt and hold gatherings, the refuge was named after the Lake Traverse Reservation’s first leader TiWakan, which means “Sacred Lodge”.

Minnesota

At the meeting point of coniferous forest, deciduous forest, and grassland (prairie) lies Cedar Creek Ecosystem Science Reserve, a unique wetland point-of-interest at the convergence of three biomes (a rare occurrence). Each biome is the result of differences in moisture regime and temperature ranges. As such, different wetland habitats can occur within these biomes. For example, white cedar swamps and sphagnum tamarack bogs can be found in coniferous forests and wet meadows can be found in the grasslands at Cedar Creek.

Wisconsin

I hope you aren’t lactose intolerant because the next stop on our wetland road trip brings us to Wisconsin, the cheese state! Following in the footsteps of our Kansas and South Dakota points-of-interest, Horicon Marsh Wildlife Area and National Wildlife Refuge is recognized as a Wetland of International Importance and is one of the largest inland, freshwater marshes in the US at 33,000 acres. Like many other wetlands in the prairie pothole region, Horicon Marsh was created thousands of years ago by glacial deposits. Visitors can enjoy over 5 miles of hiking trails and/or six miles of paddling trails in and around the marsh habitat.

Iowa

For those looking for a more hands-on wetland education, our next wetland stop brings us to the Driftless Area Wetland Centre in northeast Iowa. This nature center connects people with nature and provides ample environmental programing including ADA accessible trails to prairie wetlands, guided wetland exploration with dip nets, and a variety of displays. Historically, this location was a booming rail yard turned industry dumping ground, which led to its classification as a brownfield site. Presently, the Driftless Area Wetland Centre showcases the successful restoration of a contaminant-laden railroad brownfield site to native wetlands.

Missouri

As we continue our loop around the Midwest, we come to Marmaton River Bottom Prairie Wetland Preserve in Missouri. The Preserve exists as the largest remaining tract of wet prairie in Missouri that is unplowed, providing the area with flood mitigation and erosion prevention. To help protect the land, The Nature Conservancy periodically implements prescribed burns to bolster the growth of native vegetation and prevent invasive species from taking over.

Illinois

Turning to the north again—and continuing the trend of visiting glacier-formed wetlands—we will be visiting Cranberry Slough Nature Preserve in Illinois. This 372-acre preserve was dedicated in 1965 as the 5th Illinois Nature Preserve for its unique peat bog ecosystem. Part of protecting Cranberry Slough includes the removal of invasive brush by means of prescribed fires and mowing, which allows native vegetation to move back in. These efforts have been highly successful.

Indiana

Our next stop is a particularly exciting one. Why? Because (insert Bon Jovi singing “Livin’ On a Prayer”) WE’RE HALFWAY THERE! That’s right folks, we have made it to our 25th wetland point-of-interest, Indiana Dunes National Park. Indiana Dunes encompasses 15,000-acres of a range of habitats along and inland from the coast of Lake Michigan. A wetland type of particular note is the interdunal, freshwater marshes. As glaciers from the last Ice Age slowly melted away, they left behind successive lake shorelines and dune structures, forming these marshes (also known as wet swales) within the depressions.

Michigan

From Lake Michigan in Indiana to the state of Michigan, we will be stopping next at Humbug Marsh. Situated along the Detroit River, Humbug Marsh stands as the last mile of natural coastline along the river, which connects Lake Huron and Lake Erie. The marsh was acquired by Trust for Public Land (TPL) and is now managed by the US Fish & Wildlife Service to protect the remaining wetlands from industrialization and development, which surrounds the marsh on either side. This preserve is on the smaller side at 405 acres but is important habitat among a developed landscape.

Ohio

From one river to the next, our final destination on the Midwestern wetlands tour is the Wilma H. Schiermeier Olentangy River Wetland Research Park. Run by Ohio State University, these created wetlands offer opportunities for outreach, education, and research to students and faculty of the college—and are even open to the public! Wetland habitats within the research park include two experimental wetlands, a created oxbow wetland, naturally occurring bottomland hardwood forest wetlands within the Olentangy River floodplain, and two stormwater retention ponds.

Next Stop: Wetlands of the Southeast

While not every wetland point-of-interest was formed from receding glaciers, it is clear the Midwest is known as the prairie pothole region for good reason! Even so, the wetlands we visited during this installment of our cross-country road trip all had something unique to offer. I am excited to bring you along next time to see what’s in store as we continue our journey to the wetlands of the Southeast. In the meantime, take a break from the road tripping to enjoy the holidays. See you soon!

Written on: September 16th, 2024 in Natural Resources

By Alison Stouffer, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Welcome back to the second installment of the WMAP cross country road trip! To our returning adventurers, we are so glad you have decided to join us on the next leg of the trip. For those of you joining us for the first time, we are slowly making our way across the country as we explore a new wetland in each state of the US. If you are feeling like you missed out, you can read up about the first excursion here. Otherwise, sit back, relax, and enjoy passenger princess treatment from the comfort of your home as we head to the wetlands of the southwestern United States.

This region of the country is dominated by arid desert lands, pock-marked by low-lying basins and small mountain ranges. However, desert isn’t the only ecosystem found here; forested mountains, great plains, and intertidal coastline are also present. And throughout, wetlands (covering approximately 8% of the four southwest states1) provide a refuge for wildlife to beat the dry climate. On this leg of our cross-country road trip, we will be exploring wetland points-of-interest from Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma.

Arizona

I hope you packed your portable, battery-operated fan because the first stop of our Southwest road trip is a hot one! Tres Rios, a wetland and riparian restoration project within the City of Phoenix, is a 700-acre freshwater wetland habitat influenced by the Salt River. This demonstration site helps to re-establish the historic wetland function of the Salt River by increasing flood control within the area and removing the invasive salt cedar tree (which has pushed out native plant species like the mesquite tree). Plus, as an added bonus, Tres Rios helps filter water entering the river from the city, including reclaimed water from a nearby wastewater treatment plant.

New Mexico

From one capital to the next, we continue our journey to the outskirts of Santa Fe, New Mexico. The Leonora Curtin Wetland Preserve is a unique and rare wetland type called a ciénega, or “marsh” in Spanish, which forms around a natural spring. The 35-acre preserve is actively monitored to ensure visitation and management efforts (such as the removal of invasive plant species) are having a minimal negative effect on the habitat. This desert oasis provides critical habitat and water resources for many species of birds, butterflies, and mammals.

Texas

Our next wetland stop-over has us leaving the desert behind for Big Thicket National Preserve, which boasts over 35,000 acres of mapped wetlands! Located in a unique transition point between ecosystems, the preserve contains a range of wetland habitats, including pine savannahs with poorly draining soils, riverine floodplains that experience seasonal flooding, baygall depressions dominated by sweetbay magnolia and gallberry holly, palmetto hardwood flats where ponding can occur, and cypress sloughs that are the quintessential image of a swamp. With sea level rise, Big Thicket will likely experience a shift from freshwater to estuarine wetlands as saltwater moves inland from the Gulf of Mexico.

Oklahoma

We will be finishing the southwest portion of our wetland cross country road trip at Red Slough Wildlife Management Area in Oklahoma. Red Slough contains around 2,400 acres of wetlands, a small proportion of its historic footprint. Agricultural draining and clearing in the 1960s significantly impacted the ecological functioning of the area, which was later restored by re-establishing former hydrologic conditions. Visitors will enjoy views of mudflats, shallow-water impoundments, emergent marshes, wet prairies, riparian zones, and scrub-shrub habitats.

Next Stop: Wetlands of the Midwest

I hope you enjoyed this installment of our cross-country road trip and all the unique features the wetlands of the Southwest had to offer! We will be turning our travels north to the Midwest in the next portion of our journey so be sure to stay tuned. Until then, rest up, stretch out those legs, and start planning your return to these wonderful southwestern wetlands!

Written on: September 16th, 2024 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Research

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

As our landscape continues to change due to development and urbanization, and the impacts from climate change are ever increasing, we must adapt our ways of managing natural resources. The last generation of environmentalists (we’re talking Clean Water Act days) did a great job with point source pollution, habitat management, and pesticide control. In our current generation, ecological restoration of our already degraded systems and management adaptation are at the forefront of movement to maintain our environment. Though our love for natural wetlands runs deep, we wanted to showcase a more avant-garde management tool gaining popularity, floating wetlands. You certainly won’t find this type of wetland on the Cowardin classification system.

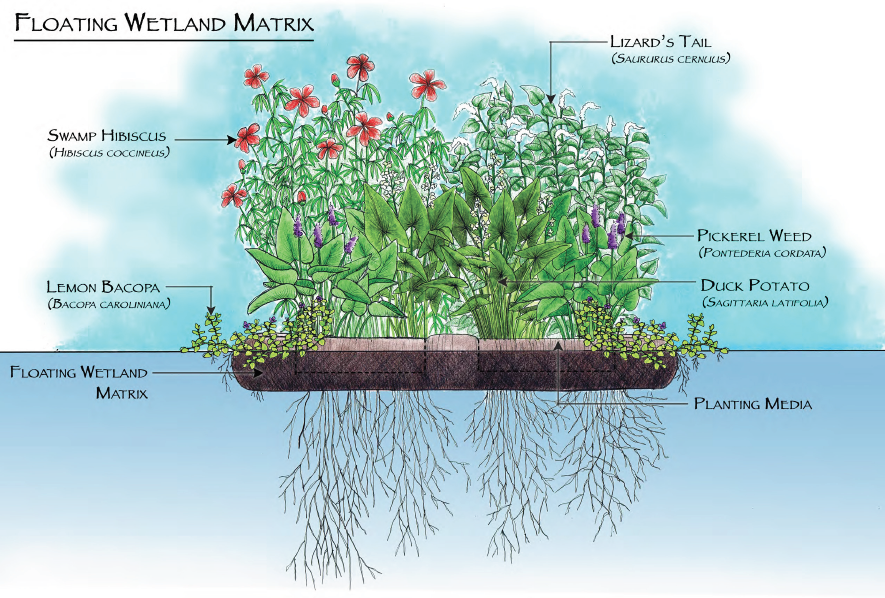

What are Floating Wetlands?

Well, the name really does say it all. Essentially, floating wetlands are tiny ecosystems created on top of a buoyant surface, then placed out into an aquatic habitat. A main component of this type of green infrastructure is that they are artificially made. The base is an artificial buoyant platform, something that can float, that is then planted with vegetation. The vegetation is primarily emergent wetland plants, meaning that the roots are tolerant of standing water and their leaves, stems, and flowers are above the water’s surface. It’s ideal that the plant species are native to the area or project region, but that doesn’t always have to be the case. Once it is complete, the platform is anchored in the water but still has enough slack to adjust to changing water levels. Your floating oasis awaits!

Benefits of Floating Wetlands

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Floating wetlands are designed to mimic the processes and ecosystem services that natural wetlands provide. It’s kind of a no-brainer when you’re using the exact plants, water, and growing conditions as a natural wetland habitat. Floating wetlands can be placed in tidal and nontidal waterways, but tidal habitat parameters can be a little trickier to work with. Let’s look at some of the benefits and advantages of floating wetlands.

Of course, every project is different. The range of benefits floating wetlands provide depend on the aquatic environment they’re placed in, type of pollution in the area, plant species used, goals and partners of the project, and the size of the structure itself. Identifying challenges and lessons learned are certainly part of any good project as well. From grant-based research to watershed management plans, as more floating wetlands are implemented the understanding of their usefulness will continue to grow.

Example Projects

It’s time to see some of these in action. The National Aquarium in Baltimore was the first place in the U.S. to test floating wetlands in a tidal system and today has over 10,000 square feet of recreated salt marsh habitat. Starting their work in 2010, the aquarium went through trial and error while navigating how to maintain a tidal floating marsh. By mimicking a habitat that once existed in the city of Baltimore, the Harbor Wetland provides green infrastructure that promotes healthy water, attracts native species like herons and American eels, and teaches visitors about wetland ecosystems. This innovative outdoor exhibit is currently open the public right next to the entrance of the National Aquarium.

Work done by the University of Washington’s Green Futures Research and Design Lab incorporated floating wetlands into a living shoreline project. The Sweetgrass Living Shoreline Restoration Project examined the benefit of floating wetlands as missing habitat on an urbanized shoreline for out-migrating juvenile salmon in the freshwater Lake Washington Basin. The floating wetlands were installed in conjunction with a living shoreline prototype and monitored for plant health, fish use, and water quality. Not only did the project provide scientific research to the lab but created educational opportunities to local indigenous youth.

Our friends over at Princeton Hydro have been into floating wetlands for quite some time now. Back in 2012 Lake Hopatcong, New Jersey’s largest lake, became the first public lake to install floating wetlands to reduce pollutant loading plus address invasive aquatic plants and nuisance algal blooms. After much success, more were installed in the summer of 2022 with help from staff and volunteers from the Lake Hopatcong Foundation and Lake Hopatcong Commission. As part of a series of water quality initiatives funded by NJDEP, these floating wetlands not only showcase project longevity but community engagement in environmental efforts.

The future of floating wetlands is bright as more research and implementation occurs in the U.S. and beyond. What can we learn from the microbial communities associated with these structures? How can we utilize them to attract specific pollinators in particular areas? Can floating wetlands compel cities to take a more aggressive approach to green stormwater infrastructure? Much like a garden, natural resource management takes tending, time, and consideration on how you want to treat the environment. The good thing about floating wetlands is that they’re a garden you won’t have to water.

Written on: September 16th, 2024 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Research

By Elizabeth Long, Delaware Sea Grant

Hi everybody! My name is Elizabeth Long, and for the past few months I have been working with Delaware Sea Grant as their Marine Debris intern! I graduated from Muhlenberg College in 2021 with a BS degree in Biology. After graduation, I moved out to Catalina Island off the coast of Southern California and worked as an outdoor educator. After leaving California, I was hoping to move back to the east coast, and was lucky enough to be given the opportunity to work with Delaware Sea Grant under their Coastal Ecology Specialist, Brittany Haywood. This was definitely a summer of learning!

The purpose of my internship was to investigate the problem of derelict crab pots in the Delaware Inland Bays. I grew up crabbing at the Jersey shore, but prior to this internship, had no idea that derelict crab pots were such a big problem, not only here, but in crab fisheries worldwide. Derelict crab pots are pots that have been abandoned or lost, usually through boat strikes, storms, or vandalism. A huge part of the problem created by these discarded pots is that they continue to trap organisms, known as “ghost fishing”. In blue crab fisheries, the most commonly ghost fished organisms are crabs, diamondback terrapins, and fish. Despite being a recreation-only fishery, it’s estimated that there are over 30,000 derelict crab pots in the Delaware Inland Bays. It’s definitely worth reading up on ghost fishing in the Inland Bays, so gather some background information on another guest blog feature from Delaware Sea Grant.

I personally became very interested in ways to reduce ghost fishing once pots have become lost. Currently, Delaware requires bycatch reduction devices (BRDs), also known as turtle excluder devices (TEDs) to be installed on all funnel entrances of a commercial-style crab pot. While not required, it is also strongly recommended to have cull rings installed on your trap, which allow for the escape of undersized crabs and small fish. I’m currently wrapping up my internship with a research project to test whether crabs have a preference as to the location of escape options in crab pots. This work could hopefully inform decisions about where escape panels or cull rings should be located should they become required in Delaware!

I also had the opportunity to help out with Delaware Sea Grant’s crab pot refurbishment workshops. The purpose of these events is to provide community members the opportunity to learn how to fix up their old or broken crab pots, and to learn about crabbing in Delaware. Locals bring their pots, and we show them how to install bycatch reductions devices, cull rings, and new line and bungees. These events always bring out people excited to learn. If you have a crab pot that needs a little love, the next refurbishment workshop is on September 27th at the Marina at Peppers Creek in Dagsboro, Delaware.

Other exciting moments from this summer included opportunities to help out in the field! First, I got to assist the Delaware Center for the Inland Bays with widgeon grass seed planting for a restoration project. I also assisted the DNREC Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program with annual transect monitoring of marsh health by looking at vegetation composition, elevation, and herbivory. These days in the field were hot and muddy, but super rewarding! It was great to get hands-on experience with the awesome work happening around the Inland Bays. Overall, I had an awesome summer working with Delaware Sea Grant and am looking forward to whatever comes next!

Looking to find out more about Delaware Sea Grant and their partners in the environmental world? Join us all at the University of Delaware’s Coast Day on Sunday, October 6th!

Written on: July 24th, 2024 in Natural Resources, Wetland Research

By Gabby Vailati and Brittany Sturgis, DNREC’s Watershed Assessment and Management Section

Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control’s Habitat and Biology Program began in the early 1990s after the passing of the Clean Water Act and awareness about local water quality began increasing. The program assessed a vast number of streams and assigned each a grade for their overall health and function. The work is ongoing and streams in the piedmont region of Delaware are being re-evaluated for habitat and stream health – go science!

The DNREC Habitat and Biology Program evaluates the biological, physical and chemical pieces of a stream and combines these components to assign a grade for a stream’s habitat quality and its biology. These grades are categorized as severely degraded, moderately degraded, good or excellent. These grades do not necessarily have to be the same; a stream may grade moderately degraded for habitat but good for biology, and vice versa. Are you curious about the health of your local stream? Check this neat resource out. The streams that are classified as severely or moderately degraded may then be placed on the State’s 303(d) list of impaired waters, meaning that they are subject to the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) process. TMDLs are meant to ensure actions are taken to limit the pollutants that enter the stream. If you’d like to learn more about Delaware TMDLs, visit here.

The first step in grading a stream’s health is to look at the biology present within the stream. We do this by collecting any and all aquatic macroinvertebrates (bugs) that live in the stream – we love finding those critters that live under the rocks! These types of bugs are important because they live a portion of their lifecycle within the stream itself. We use different field techniques to find the bugs while they are living in the water. The aquatic macroinvertebrates are important because we know that certain bug types can tolerate pollution, while others cannot (mayflies, stoneflies and caddisflies). If a stream has a lot of the intolerant bugs, then it scores a higher grade for biological stream health because the intolerant bugs are very sensitive to water pollution.

After we collect bugs, we perform a stream habitat assessment to look at the health of the surrounding land. Some habitat characteristics that are evaluated include the vegetation type along the bank, the amount of sediment/dirt that has accumulated within the stream, the amount of overhead shade, the number of riffles (think ripples in the water around rocks), or how embedded rocks are in the ground of the stream. How embedded rocks are within the ground can tell us about available surface area a bug has for shelter and reproduction. A rock only 25% embedded in the ground provides a niche habitat and is most ideal, while a rock embedded about 75% in the ground is less than ideal with less surface area available for use by the aquatic macroinvertebrates. Riffles, where rocks may break the water’s surface and create bends in the stream, are a great way to judge habitat in a stream as well. Riffles attract a wide array of bug types and make a stream more diverse. These factors can help tell us about the different habitats available in the stream, or the stability of the stream. Water quality parameters (dissolved oxygen, nitrogen, etc.) are also collected at each site. We then combine all of the bug, habitat and water quality scores to rate and score the stream.

All of this is a fancy way of saying our streams are very important. Whether used for recreation or drinking water or wildlife habitat, these streams feed into larger bodies of water that we all rely on. Keeping these streams healthy benefits all of us in the long run. Next time you’re near a stream, take a moment to appreciate all the tiny, diverse bugs that call it home and remind yourself that these streams are a small part of a much larger system of water.

Written on: July 22nd, 2024 in Natural Resources

By Alison Stouffer, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Have you ever wondered what wetlands look like around the country? For the most dedicated among us, you might travel to all 50 states to find out. Alternatively, you can grab your favorite car snack (mine is Twizzlers), get comfy on the couch, and buckle your metaphorical seatbelt as you join me on the first installment of the WMAP cross country road trip. Today we are headed to the wetlands of the western United States!

Despite covering almost half of the land area of the United States, the western states, specifically west of the Rockies, contain very few wetlands. Less than 5% of each state is covered by wetlands, excluding Alaska, which boasts 43% land cover by wetlands (the largest in the US!) 1. However, the West is a highly varied region of the country where you can find marine west coast forest, tundra, desert, boreal forest, rocky shores, northwestern forested mountains, great plains, and tropical forests. With such a wide range of ecosystems comes a wide range of wetland types.

As each state contains multiple types of wetlands, we have a road trip packed full of interesting stops which only allows time for the occasional bathroom break, one wetland point-of-interest per state, and the necessary pitstops for food and fuel.

Alaska

Today we will be visiting Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska’s largest boreal wetland basin and the third largest wildlife refuge in the nation. Located at the junction of the Yukon, Porcupine, and T’eedriinjik (Chandalar) rivers, the refuge encompasses around 11.1 million acres of low-lying wetlands and a mosaic of approximately 40,000 small lakes and streams. While multiple types of wetlands are present within the Yukon Flats, boreal peatlands (specifically bogs) are of special note due to their insulating properties that help protect permafrost from thawing over the spring and summer months. This is particularly important since permafrost stores carbon, helping to combat climate change.

Washington

A short plane ride south and we are at our next stop, Mount Saint Helens Wildlife Area in the state of Washington. Encompassing approximately 10,500 acres of land, this wildlife area contains a variety of wetland and riparian habitats, including tidal mudflats. The tidal mudflats are a type of non-vegetated wetland that can be found along the North Fork Toutle River and is the result of an eruption of Mount St. Helens in the 1980s.

Oregon

It’s just a quick hop, skip, and a jump south to Oregon, where we will be trading in our vehicle for a vessel. So grab a kayak or canoe, zip up your lifejacket, and paddle on to Blind Slough Swamp Habitat Reserve. Located along the Columbia River, this habitat reserve protects a pocket of forested Sitka spruce swamp, a small remnant of a previously common wetland ecosystem that has been logged and diked for pasture. Sitka spruce trees are salt-tolerant with elevated root platforms to help them thrive in brackish swamp environments.

California

Continuing our road trip south along Highway 101 to California, we will be chugging along down to SoCal to visit an island system just offshore from Santa Barbara. Channel Islands National Park consists of 5 islands located in a unique spot with significant upwelling where cool, nutrient-rich ocean currents mix with warm coastal currents. These characteristics, in conjunction with shallow, clear waters, create the prime conditions in which seagrass (a type of submerged aquatic vegetation or SAV) beds can grow and thrive.

Nevada

Hope you’re A/C is working because it’s going to be a hot one! Having driven down the Pacific coast, we will now be turning our road trip east towards the state of Nevada and the Mojave Desert. Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge is the epitome of a desert oasis. Fueled by the Amargosa River, an underground river, this refuge encompasses approximately 12 spring systems. Pools form around these springs creating unique wetland habitats for a range of plants and animals found nowhere else in the world.

Utah

Our desert adventures continue as we head northeast to the Bonneville Salt Flats, a 30,000-acre barren patch of salt encrusted land. Crust depths range from one inch along the edges up to five feet near the center. The Bonneville Salt Flats are a remnant of the ancient Lake Bonneville, which deposited the salt layer seen today as it dried up. Despite its inhospitable appearance, the salt flats are a unique example of playa wetlands. Playas are seasonal lakes that remain dry until a rain event. For the flats, the wet season runs through the springtime, inundating the area with a thin layer of water that will eventually evaporate; thus, continuing the cycle.

Idaho

All the salt from Utah made me hungry for fries, so we shall continue our drive north to Idaho, the Potato State. With everyone’s favorite form of potato in hand, we will now be stopping to explore the freshwater marshes of Harriman State Park. Charged by Henry’s Fork of the Snake River and freshwater springs, this park boasts an abundance of marsh on the fringes of several water bodies scattered throughout the park. As such, their level of inundation varies seasonally with precipitation and water levels of the river.

Montana

Zigzagging our way east again, we are headed to the northern Great Plains of Montana to stop at a Nature Conservancy property called the Comertown Pothole Prairie Preserve. These pothole prairies formed from glaciers scraping along the terrain leaving behind a collection of small depressional wetlands that fill with snowmelt in the spring. The Preserve protects this unique ecosystem from agricultural plowing, in turn protecting a handful of threatened and endangered waterfowl and bird species that breed in the shallow waters.

Wyoming

Road trips can be long and boring with so much driving. But it is always worth it once you make it to your destination. On this stop, we will be visiting the 4th most popular National Park in the United States, Yellowstone National Park. Wetlands account for over 10% of the park, with some hydrothermal pools – a distinguishing feature of Yellowstone – falling within this classification. While the extreme heat creates challenging conditions for survival, it hasn’t kept thermophiles (heat loving organisms) away!

Colorado

The end of our road trip is near as we continue south to my favorite state, where I was born and raised, Colorado! Rather than visiting a specific park, refuge, or preserve, I thought we would explore the fens and wet meadows of Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison (GMUG) National Forests. In Colorado, these wetlands are found in high-elevation, low temperature montane and alpine regions and are fed by snowmelt in the late spring and summer months. There are an estimated 1,700 fens within GMUG National Forests.

Hawaii

For the final stop of our wetland road trip (part 1), we will be flying to Hawai’i Island to visit Kaloko-Honokōhau National Historical Park. Wetlands are an integral part of the natural and cultural significance of this park. One example is that of the unique anchialine pools, some of which were historically used for aquaculture. These brackish pools form in nearshore lava beds where freshwater from land mixes with saltwater from underground tunnels connecting to the ocean. Despite being a rare habitat, over 200 of the ~1,000+ pools found worldwide are located within the boundaries of the National Historical Park.

Next Stop: Wetlands of the Southwest

We covered a lot of ground on the first installment of our cross-country road trip! Those wetlands that we were fortunate enough to visit here are only a smattering of what the United States has to offer. Be sure to reserve your spot for the next chunk of our road trip, where we will be headed to the states of the Southwest. Until then, rest up, stretch out those legs, and start planning your return to these wonderful western wetlands!

Written on: July 22nd, 2024 in Education and Outreach, Natural Resources

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Get your gloves out and your hoses turned on, we’re going to the garden to get to know wetlands in this blog installment. Now the hobby of gardening may seem like a daunting task, and taking care of plants may seem even more challenging to the novice. But you don’t need a huge yard or diggable ground to get into this type of landscaping – gardening with wetlands in mind. Ranging from peat-free soil to making a mini wetland at home, one small step can help us take a leap forward in how we view our mosaic landscape, all while representing wetland habitats.

While our backyards cannot fully recreate the expansiveness of a natural wetland, these micro-ecosystems represent, and even perform, some of the same functions as large wetlands do. Some of those similar functions are to restore and boost biodiversity, improve water quality by filtering out pollutants, and reduce or mitigate flooding and storm surge. These gardening practices also provide habitat for beneficial critters like pollinators or aquatic insects, and can be filled with native plant species – which require less water and pesticide use! Some of the more intrinsic enjoyments have to do with how we find happiness in nature; wetland gardens or landscapes with water features can be a calm space to rest our busy minds after a long day. Everything from boosted physical activity to decreased stress levels, its pretty well-know that being outside is a good thing.

Let’s dig into how to garden with wetlands in mind.

Mini Wetland Container Pond

Who doesn’t love a good repurposing project? This type of wetland garden is great if you have a balcony or patio, plus can repurpose something from your home like a wooden barrel or old sink; be sure the container is watertight. Start by finding a space that gets some sun but doesn’t have full sunlight all day long, then place whatever container you’re using in its spot before adding a layer of clean gravel or small stones at the bottom. Next, it’s best to create varying levels in the container using pieces of wood or rocks, making an easy in-and-out route for visiting critters and providing spots for plants to sit on if needed. Then, get planting. You only need a few aquatic plants to oxygenate the water and provide habitat. Also, picking plant species that like to be submerged or that can survive just on the surface is best – utilize your local garden center or pond supplier as a resource. Last, fill it with water. It’s ideal to use rainwater since it has fewer chemicals than tap, so feel free to collect some ahead of time. Nature will do its magic with little maintenance required, the plants should clear up any algae, and wildlife may come next.

Going Peat-free In Your Garden

If you’re trying to make environmental conscious choices at home, the supplies or materials you use in landscaping is a great place to start. We’ve talked before about the importance of peatlands and the use of peat on our blog, but long story short; peat takes a really long time to form, and when it’s removed from wetlands for gardening supplies it releases stored carbon dioxide back out into the atmosphere. Which isn’t good. So, the moral of the story is, use peat-free soil or compost. It allows you to play a role in the fight against climate change and protects the exploitation of crucial wetland habitats. Just remember that soil and compost are two different things and be sure to read the label closely on both. Labels such as “peat-reduced”, “natural”, or “environmentally friendly” say nothing about the peat content in the product. On the bright side, some suppliers are promoting peat-free alternatives such as wood fiber and coconut coir. There are even recipes out there to make your own peat-free potting soil!

Rain Gardens

As a tried-and-true eco-friendly landscaping method, rain gardens have been around since the 1990’s thanks to our neighboring state of Maryland. Also called bio-retention ponds, rain gardens are shallow hollows or depressions that collect rainwater and allow it to gradually drain into the soil. These areas are designed to cope with conditions from droughts to floods and are planted with water-loving species that provide benefits to humans and nature alike. Below are some of the characteristics and benefits of a good rain garden.

Rain gardens provide some similar value and functions as natural wetlands and are a simple way to protect your watershed. Other factors that come into play when trying out this method are size, location, soil type, plant species, and maintenance. If you’re looking to install a rain garden in Delaware, or just want more information, visit these three rain garden resources: University of Delaware Cooperative Extension, DNREC Yard Adaptation, and Delaware Nature Society.

Mini Drainpipe Wetland

Now this technique is a must-try at home, you’re going to turn your drainpipe into a wetland. This wetland has three parts: a gravel filter pot that keeps your water free from debris, a drainage area that is rainwater-fed with aquatic and wetland plants, and another drainage area that is a mini floodplain to release water slowly. The materials needed for this are not a heavy lift, but it may take a few hours to create the entire wetland system. You will need: two big containers or tubs, sand or clay soil, aquatic and water-loving plants, peat-free aquatic soil, stone/wood/brick/mud for bonding material, a small sheet of membrane for water to pass through, horticultural grit, and gravel. It may seem like a lot, but the result is something quite amazing that filters runoff while being an attractive feature that also provides a source of water and habitat for small wildlife. You can create this habitat in the tiniest, most urban of settings and boom – you’ve turned your boring downspout into your very own wetland preserve. A more detailed step-by-step process is available here.

One of the biggest landscaping challenges is changing your perspective on what is beautiful or useful in your yard. It’s time to get rid of that green, manicured lawn and rip out those Bradford pears. Turn off your irrigation and hit up your local native plant nursey while you’re at it. As this shift in the paradigm grows, there is more room for wild and wonderful yard practices like gardening with wetlands. Whether you have an acre, a side garden, or a rooftop terrace, it’s easy to take steps in creating a mini wetland of your own that provides the value you want. The landscape practices we covered not only enrich our current gardens or outdoor spaces but provide an ecosystem we can continue to learn from. Using a “green thumb” is easier than you think – help us build awareness of the value of wetlands in your own backyard.

Written on: May 20th, 2024 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Restoration

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

For any homeowner with a dock leading out to tidal waters in Delaware or any boat angler who likes to put in at a public ramp and go crabbing, fishing or just boating around the Inland Bays, you are familiar with the issue of rivers shoaling and channels silting in. It is a nuisance to live with but it’s an indication of a larger coastal issue related to shoreline erosion and movement of sediment and DNREC is working towards a solution.

It is no secret that Delaware is losing coastal habitat and wetlands to the impacts of sea level rise and erosion. As coastal wetlands become permanently flooded by rising water levels and wash away the dirt, or sediment, gets stirred up, carried away, and settles into deeper channels. Similarly, when severe storms and destructive wave energy erodes a coastal wetland apart, those sediments wash into the waterways and settle in channels. This pattern repeats daily and eventually the river channels start to build up, becoming shallower. This cycle can continue until channels are so shallow it isn’t safe to boat on them. Other sources of sediment, such as from construction runoff or storms, also contribute to in-channel build up.

The Idea

Dredging navigable channels to keep them wide and deep for easy boating has been going on for decades. Historically, the material collected was pumped into a contained disposal site, a big land-based dirt bathtub if you will, where the water could drain out and the sediment would remain. In these upland disposal sites, rich aquatic sediments are stored and not put to any use. The thinking behind beneficial use of dredge material is to put sediment back where it came from and where it can do some good. Place the dredge material carefully on wetlands that are stressed, sediment-starved, eroding and sinking. When done thoughtfully, this addition of material gives wetlands an elevation boost to stay ahead of sea level rise, as well as a nutrient boost to encourage strong plant communities and therefore soil stabilization.

Beneficial use for wetland restoration can be done in several ways. Thin-layer application is when a few inches up to a foot of material is added to an existing wetland that needs help. Conversely, thick-layer application of up to several feet of material can be used to rebuild a former wetland that has already disappeared. In the middle, dredge sediment can be used to ‘fill potholes’ in wetlands that still exist but are experiencing pooling or break-up, and where big sections are failing and falling apart from the inside. In all cases, the results will be muddy at first as added material dries out a bit and plants start growing back in. Full recovery can take a few years, so be patient.

Working Together

Bringing the world of dredging together with wetland restoration requires careful consideration of the plant community, sediment types and weight, dredge volumes and wetland elevation, sediment containment and tidal connection, sustainability and even aesthetics. In 2012, DNREC completed its first beneficial wetland restoration demonstration project at Pepper Creek and Piney Point Wildlife Area. This was a collaboration between two DNREC programs: the Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program and Waterway Management Section. Each program specializes in specific, technical work that when put together, allowed the thoughtful execution that turned out to be a success.

The many lessons learned from 2012 are being put to good use today as DNREC is working on several dredge and beneficial use wetland restoration projects on the Delaware Bay and Inland Bays. Each project presents its own challenges and specifics, and each has its own timeline. It’s an exciting time for DNREC to build the knowledge and skills to take the lead in tackling two big topics at once. Together, these projects will improve navigation in Delaware’s waterways and increase and improve coastal wetland habitat and water quality.

How This Impacts Boaters

During dredge operations, residents will be able to see and hear the dredge equipment working and running. Operation hours may depend on the day of the week and staffing, but also factors like tide and weather. Safe working conditions for everyone involved is a priority. Likewise, the wellbeing of fish and wildlife is important, so operations may be required to stop for several months in accordance with state and federal requirements to allow many species to nest and breed in summer months. This varies by location and project.

Pipelines will extend from the dredge to the beneficial use sites, sometimes a short distance, sometimes several miles. Pipelines often float and are visible and should be marked with buoys, but boaters should be on alert and stay a safe distance away. Visit DNREC’s Shoreline Management webpage to stay informed on when and where these projects are happening.

The future is bright for DNREC as several programs come together to increase our capabilities and help solve multiple environmental issues at once. Beneficial use for wetland restoration is still an emerging field and DNREC is proud to be exploring new technology to address issues.