Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube RSS Feed

Written on: May 19th, 2023 in Natural Resources, Outreach

By Joe Schell, DNREC’s Delaware Community Conservation Assistance Program (DeCAP)

When you think of the word habitat – what is the first thing that comes to mind? Is it the dawn light painting your favorite meadow with wisps of amber and gold? Or maybe it’s the cool, crisp water of a stream full of fish and aquatic insects. For me it brings me to a warm spring morning in an old growth forest, as the trees fill with the sound of birdsong. Whatever you envision, the common theme is probably something that is far removed from people. But what if habitat didn’t have to be separate? What if habitat was your very own backyard?

Before homes, neighborhoods, towns, and cities there was just habitat – a home for plants and animals. When we consider it this way, thinking of our backyards as habitat doesn’t seem so out there. This is a big part of the reason we’ve seen urban conservationists advocating for homeowners to convert our backyards from traditional lawns to more natural landscapes like pollinator meadows.

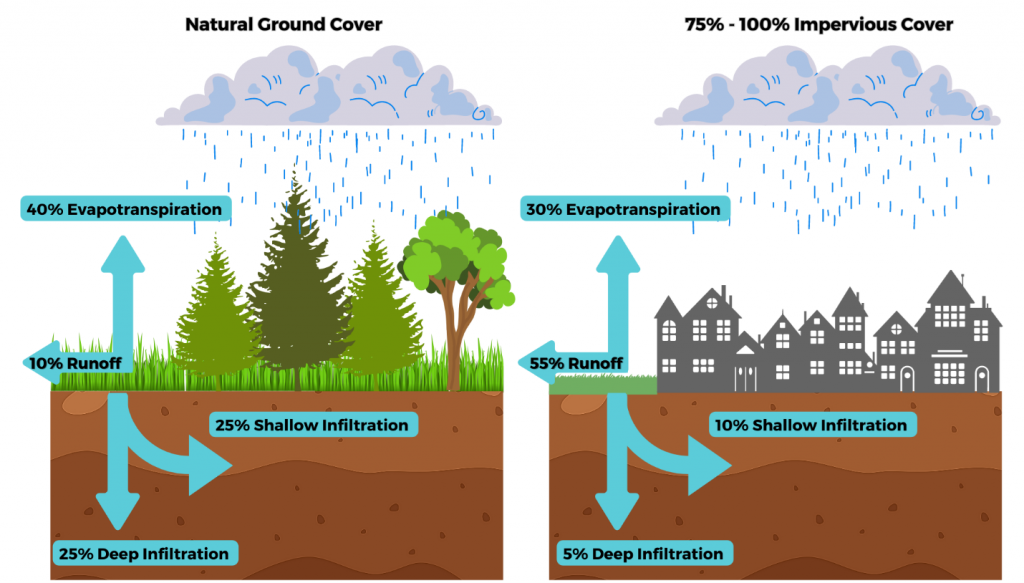

But habitat is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to benefits of native landscaping. Thinking of your backyard as an ecosystem has the added benefit of improving our watersheds! To visualize this, picture a rainstorm in a forest compared to a rainstorm in your town or backyard. They’re different, right? Some water can be absorbed in both, but much of the water in a neighborhood flows out or runs off through ditches and pipes. When this water enters our storm drains it takes any pollutants with it which eventually ends up in our streams, rivers, ands bays.

So, the trees we plant, gardens we tend, and practices we provide can not only create habitat, but also help clean and filter the water running off our homes, yards, and driveways. This all sounds great, but how do we go from lawns to landscapes? The “how” can take many different forms which we can call best management practices (BMPs). Let’s look at a few BMP examples.

Conservation Landscaping

Conservation landscaping is defined simply as the conversion of managed turf grasses to meadow. As a practice this has many benefits. These meadows provide our pollinating insects with important habitat. Beyond providing food, you also provide homes for beneficial insects. For example, sweet Joe-Pye weed (Eutrochium purpureum), in addition to its beautiful flowers, has stems that Delaware native bees love! These stems are hollow and during the winter months, native leafcutter (Megachile spp.) and mason bees (Osmia spp.) will use these as locations to lay eggs.

On top of these habitat benefits, landscaping with native plants instead of a managed lawn can promote healthier waterways. Most turf grasses used in lawns are not native to Delaware and can require maintenance like fertilizer, herbicides, and supplemental waterings. And for the volume of water a lawn needs, it doesn’t absorb that much of it increasing stormwater drainage needs. In some cases, 90% of the water that hits your lawn may run off it. Native plants are adapted to Delaware and don’t need as much maintenance to survive. In fact, once established and in the right habitat most native plants don’t need any supplemental waterings, all while absorbing excess water.

Rain Gardens

Conservation landscaping does a great job at reducing runoff, but a rain garden takes it to the next level! As the name suggests, these bowl-shaped gardens are designed specially to take in the excess stormwater from your home and lawn. The bowl shape design allows water entering the garden from your lawn, roof, and driveway to slowly infiltrate into the soil over the course of 24-48 hours. In terms of protecting our waterways, this is a huge benefit to water quality. Many of the major threats to water quality come from non-point source pollution – that is the small amounts of pollution such as sediment, oil, fertilizer, and other contaminants that wash away during storm events and eventually into our rivers and bays.

Plants in these practices are selected both for hardiness and their hydrophytic (wet-loving) nature. Native shrubs like inkberry holly (Ilex glabra), red-osier dogwood (Cornus sericea) and perennials like blue flag (Iris versicolor), and swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) are perfect choices for rain gardens.

There is a lot more that goes into these practices when it comes to proper planning, installation, and maintenance. Fortunately, DNREC is offering a new program to help landowners on their water quality landscaping journey! The Delaware Community Conservation Assistance Program (DeCAP) provides both technical and financial assistance to homeowners, schools, and non-profits interested in practices like rain gardens and conservation landscaping. Whether you are looking to create habitat, improve water quality, or beautify your home, discover DeCAP and began your landscaping journey today.

Written on: May 19th, 2023 in Natural Resources, Wetland Research

By Kayla Clauson, DNREC’s Watershed Assessment and Management Section

When you think of submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV), Delaware may not be the first state that pops into mind (we can’t be the first state all the time!) When SAV comes to mind, you may first think about the world-famous seagrass, Eelgrass (Zostera marina). In a marine environment, Eelgrass certainly runs the show being the only true seagrass in our region. However, there are a variety of other important species that exist in our less-salty waters. SAV can be found across different salinities, from saltier coastal oceans and bays, mixed estuarine rivers, and freshwater streams. In fact, as salinity of the water decreases, SAV species diversity increases!

So, what makes SAV unique? Submerged aquatic vegetation is any rooted, aquatic plant that grows entirely underwater. Like terrestrial plants, aquatic plants even flower and produce seeds for pollination underwater. These aquatic plants are important because they improve water quality by filtering pollutants and even trapping sediments that improve water clarity. These underwater plants face different challenges compared to their terrestrial relatives. One of the main stressors in Delaware is turbid or murky waters, which limits the sunlight in the water column that is needed by plant’s to grow

Although SAV is known to be important habitat, there have been minimal efforts to quantify what plants we have and where they exist in the First State. That’s why last year DNREC scientists began an official monitoring of SAV in freshwater streams across the state. Biologists visited 12 locations, looking at 9 different waterbodies and surveyed 6 miles of streams. These surveys documented 12 different species, with the most at the Brandywine Creek State Park. SAV beds ranged in size from dinner plates all the way up to a school bus! Among the beds were also various animals that benefit from SAV presence, including snails, freshwater mussels, and crawfish.

These survey results will be saved and added to more data collected this upcoming summer as DNREC works to catalog where and what SAV exists in Delaware. This information will help DNREC track SAV and work to increase populations of this beneficial plant community in the future.

SAV Spotlights: Check out some of Delaware’s SAV findings!

Written on: May 19th, 2023 in Natural Resources, Outreach, Wetland Research

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Celebrate good times, come on! Yes, it’s the holiday we’ve all been waiting for – American Wetlands Month. This May marks the 32nd anniversary of recognizing the vital importance and need of wetland habitats across the United States. Now our program is out here everyday living and loving wetlands, but of course we greatly appreciate a designated celebration for the ecological, economic, and social health benefits that wetlands provide. To take it a step further this month, we wanted to educate folks (and even ourselves) about the challenges wetlands are facing as a natural resource across the world. Let’s take a stroll through some global wetland newsmakers.

Australia

Serious debate surrounds the Murray River, Australia’s second-longest river, as its floodplains may become one of the first attempts to engineer wetlands for water offsets in the world. Victoria, Australia has immense amounts of forested area, some of which are inhabited by First Nations people, that rely on regular flooding for survival. The Murray-Darling basin along the river has around 30,000 wetland pockets that are drying out due to climate change and the demand for irrigation by farmers. To address the problem and keep the wetlands alive with less water, the Victorian government has turned to floodplain infrastructure with nine major wetland engineering projects which have a $214 million USD price tag. Essentially the projects would artificially enable flooding in wetlands and surrounding areas, including ones of ecological and cultural significance, and provide water for farmers. The projects will go through an environmental assessment process this year, and the government is pushing its engineering initiatives through the Victorian Murray Floodplains Restoration Project. Citizens, scientists, and policymakers of Victoria have vocalized major concerns about the engineering projects, siding against the governments problem-solving effort.

Colombia

With almost 35% of Colombia’s land area covered by the Amazon rainforest, many citizens of the country are seeing the impacts of deforestation and exploitation of natural resources. In southern Colombia, throughout the wetland area of Lake Tarapoto, women of Indigenous communities are combating these changes through scientific research and education. Lake Tarapoto’s wetlands not only provide habitat for critical plants and animals, but support livelihoods for 22 Indigenous communities that heavily rely on aquatic resources such as fish and boat transportation. These women have stepped up to the plate to monitor, manage, and educate locals on the importance of wetland restoration, as well as increase awareness on the impacts from overfishing. The incredible work they have done over the years has caught the eye of environmental organizations like Amazonía Verde and Conservation International. Ichthyology (the study of fish), restoration, species research, community agreements – these women are doing it all for the wetlands and waterways.

Nigeria

In the Sahara of northern Nigeria lies the remnants of the Hadejia-Nguru wetland which once supported the livelihood of two million people and critically important habitats for migrating water birds. Big changes occurred in the 1990’s when the Nigerian government constructed two dams that together captured 80% of the water that flowed into the wetland areas. What has happened in the last 30 years is an oasis gone missing; most all the wetlands have dried out and majority of the population has left the area. The very little remaining wetlands are currently major centers of community conflict between farmers and herders as the desert invades their space to survive in poverty. As the uncertainty remains for the humans and biodiversity alike in this area, the one thing that is for certain is that issues need to be addressed for the first Ramsar site designated in Nigeria.

China

Now this is a different take on a wetland species we in Delaware hold near and dear to our hearts. China is experiencing an invasion of Smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) and has even launched a nation wide effort to control the species by 2025. Though the plant has been around in China since 1979, in the past few years it has taken on a life of its own spreading across tidal mudflats and increasing concerns for the government about the impacts on shipping channels and aquatic farms. Even more at risk are the birds migrating along the East Asian–Australasian Flyway, one of the most critical flyways in the world for coastal water birds. This invasive to the country has spread to many provinces where local control is simple not enough, and officials are suggesting management plans be pushed up through the National Forestry and Grassland Administration.

Indonesia

This video speaks for itself, but it is too impactful not to share. The country of Indonesia is made up of over 17,000 islands including small coastal countries such as Java, Sulawesi, and Sumatra, while also being the fourth most populated country in the world. What is even more astonishing is that this country is losing hundreds and thousands of hectares of land (1,000 hectares = 2,400 acres) in the last two decades due to erosion and sea level rise, with majority of impacts effecting large areas of mangrove wetlands. According to the Center for International Forestry Research, Indonesia is home to 3 million hectares (7,400,000 acres) of mangroves equating to 23% of the worlds mangrove area. With wetland restoration and habitat management a focus but a slow-moving train, the communities and wetlands throughout these island nations are at serious threat,

Current projects, critical issues, policy updates, success stories – going worldwide with wetlands can certainly enlighten the most novice of nature fans. As we go through the next half of American Wetlands Month, our program challenges you to keep up the reading; see what you can learn or share about wetlands near and far. Like the old adage says, knowledge is power.