Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: December 19th, 2022 in Wetland Animals, Wetland Assessments

By Brittney Flatten, DNREC’s Watershed Assessment and Management Section

For the past year, I’ve been working with another DNREC scientist to document submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) in Delaware’s streams, ponds, and bays to get a better understanding of where these plants like to grow and how we can protect them. I had previously observed some SAV in a nearby stream while doing a wetland assessment in Blackiston Wildlife Area and we decided to check it out. When we arrived, however, we were surprised to find that the stream barely had any water! Though the summer of 2022 was dry, the lack of rain didn’t fully explain what happened. So, we walked around for a few minutes to find more clues. We saw a lot of downed trees, but they hadn’t been cut down by humans or blown over by wind. Instead, most of the stumps had been sharpened into points like this:

Right away, we had a pretty good idea of what happened. The responsible party was Castor canadensis, a large rodent better known as the North American beaver. These furry creatures can be found here in Delaware, throughout the rest of the United States, and even northern Mexico. The beavers had built a dam upstream of our survey site, which altered streamflow in the area. While we didn’t find the SAV we were looking for, we stumbled upon an ecosystem undergoing a natural process of change, which was equally cool to see.

Why Do Beavers Build Dams?

Beavers have an instinct to modify their habitat by building dams. Scientists agree that beavers build dams to protect themselves from predation. Water builds up behind the dam, creating a pond. In the pond, beavers will make another structure called a lodge where they live, eat, and store extra food. Lodges have escape tunnels that allow beavers to exit into the pond if they are in danger. Plus, their large tails and webbed hind feet make them excellent swimmers, so predators like coyotes, bobcats, bears, and birds of prey have a difficult time catching them. Ponds also provide great habitat for aquatic plants which are part of the beaver’s herbivorous diet in addition to tree bark and leaves.

Beavers and Wetlands

Beavers are often viewed as a nuisance by humans because their activity can flood farmland and damage private property. However, beavers are a keystone species in wetland ecosystems since they are the creators of wetland habitat. Keystone species have a large impact on the wellbeing of other organisms, and their ecosystem would drastically change or cease to exist without them.

Just like other types of wetlands, excess nutrients created by beaver activity supply a variety of ecosystem services. Slower streamflow and dams trap sediment and nutrients in the pond, which prevents water pollution downstream. Dams in incised streams, where the water no longer reaches the top of the banks, can help reconnect the stream to its old floodplain. Deposition behind the dam and in the floodplain creates rich soils for wetland and floodplain plants, which serve as food and habitat for many different animals like turtles, frogs, birds, and insects. Compared to human-built dams, beaver dams are easier for fish to navigate while traveling upstream. Water storage in beaver ponds can help to maintain water levels during dry periods and lessen the force of floods.

Due to their importance, beavers are considered potential tools for restoration, particularly in the western United States. Structures that mimic beaver dams, which are called beaver dam analogs, or reintroduction of live beavers to an area are strategies that can be used to restore an impacted ecosystem to its previous function.

Where To Learn More

Since us humans and beavers share the same environment, we must work to find solutions that meet the needs of both populations. If you have questions or concerns about beavers in your area, you can contact your state’s fish and wildlife agency. If you live here in Delaware, you can visit DNREC Fish and Wildlife or call (302) 735-8683. The Beaver Institute has fact sheets and papers that cover a wide variety of topics relating to beavers and a list of resources to solve beaver-related problems.

Written on: December 19th, 2022 in Education and Outreach

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Ah, yes. The terrestrial ecosystem of bland, brown stuff. The innocuousness of peat may look like just any run of the mill soil, but this dirt is way beyond your average stuck under the nail type.

Peat, Peatlands, and Wetlands

First things first. Peat soil, or peat, is formed when an environment has a lot of water, low pH, low nutrient content, and low oxygen supply. All these factors come together to slow down an area’s plant decay and result in the build-up of partially decomposed plant remains in the form of soil. Peatlands are a type of carbon-rich wetland that accumulates layers of peat over time, and in some cases even thousands of years. These habitats occur in almost every country in the world and represent nearly half of the world’s wetlands.

How these habitats look on the ground is a bit more complex; every country is a little different. For simplicity’s sake, peatlands worldwide are commonly divided into bogs, fens, and mires. The water source, amount of water, and chemical composition of the water entering the system often determines the type of peatland in an area. Based on the map above, it’s clear that the majority of the world’s peatlands occur in the Northern Hemisphere, but don’t knock the Southern Hemisphere out completely. In cooler climates, such as the boreal regions of Canada and Russia, peatland wetlands are mostly the build-up of mosses, shrubs, and sedges. In warmer climates, such as Southeast Asia and Central Africa, tropical peatlands are in dense forested areas near low altitudes.

Why Do Peatlands Matter?

The naturally growing layer of organic matter (the peat) is the secret ingredient to this wetland’s importance. Since the plants in these habitats don’t fully decompose, the carbon dioxide (CO2) captured during photosynthesis actually becomes locked in the peat soil. These very specific water-logged conditions allow for peatlands to sequester, or capture and store, carbon that would otherwise be released to the atmosphere, contributing to global warming. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), peatlands currently cover around 3% of the earth’s land surface, but store around 33% of the world’s overall carbon, which represents more carbon than in all forests combined worldwide. Aka, they are the largest natural terrestrial carbon store. Here are some other benefits peatlands provide:

Peatlands in Delaware

A sight very rarely seen, peatland wetlands in the first state are seen in the form of fens. These non-tidal wetlands occur in deep, organic peat that is nutrient-poor and extremely acidic. Unique to the Delaware landscape, fens have standing water throughout the year and develop at the bottom of moderate slopes as groundwater is forced upward by clay soils. So where can you find these habitats? Well, you won’t see them at your local nature preserve trail. When we say rare, we mean it. Peatland fens can occur within two places in Delaware; complex stream corridors associated with Atlantic white cedar, and edges of salt marshes where there is acidic groundwater seepage. DNREC is still working towards accurately mapping the locations of these small, essential habitats to protect them and the sensitive species that call them home.

Threats to Peatlands and Their Future

In the past, the mining and burning of peat as a fuel was used in many developed countries which we learned was a big no-no. But today those same countries still use peatlands for agriculture, forestry, and horticulture. When drained or burned (as wetlands sometimes are) these areas transform from carbon sinks to carbon sources. What this means is that the large amounts of carbon that were being stored within the peat soils is being released back into the atmosphere. As the peat is exposed to air and releases its carbon in the form of CO2, it comes out around 20 times faster than it was sequestered. Yikes. The United Nations Environment Programme estimates that 10% of all annual fossil fuel emissions are from drained and burned peatlands. The effects of this problem can trickle beyond carbon emissions. Science has already seen increases in carbon footprints, reductions in land surface, increases in flooding, the thawing of permafrost causing peat to dry out, and increases in dry land creating potential for wildfires.

The good news is all hope is not lost. First and foremost, peat is not a renewable resource, it’s a fossil fuel. If there is anything the current climate emergency has shown us, it’s that using fossil fuels has had bad environmental consequences. On the ground level, do your homework on where everyday products or items come from. Avoid purchasing wood, flooring and wood-based panels in particular, that are sourced from destroyed tropical habitats in places like Southeast Asia and South America. Stay up-to-date on mining activity and become informed on how to speak out against the destruction of Arctic regions for mining sources; some of the most popular minerals include coal, lead, nickel, and precious metals. Next up, let’s plan for the future learning from mistakes made in our past. A crucial way in doing this is through “good governance”, or more responsible regulatory framework and legislation, especially regarding non-tidal wetlands like peatlands. Upgrading permit regulations to protect these crucial habitats, as well as including what restoration may be required after their disturbance, is a key step in keeping them around for the future. And, as always, reduce your carbon footprint and emissions on a regular basis – calculate your carbon footprint and take action now.

The conservation of peatlands can not only reduce carbon emissions, potentially on a global scale, but increase biodiversity of flora and fauna. The restoration of these areas provides insight into new techniques for a sustainable future while reviving essential ecosystems that provide services for the people and planet alike. And hey if Alec Baldwin has something to say it could be worth a listen.

Want to discover more about peatlands? Browse through these organizations doing incredible wetland work!

| Global Peatlands Initiative | Wetlands International | Project Drawdown’s Peatland Protection and Rewetting |

| American Forest Foundation |

Written on: December 19th, 2022 in Education and Outreach

By Melanie Cucunato, DNREC’s Division of Parks and Recreation

Did you know that Delaware is home to 34 Nature Preserves?! …What even is a Nature Preserve you ask? First off, ouch. Second off, allow me to attempt to give you the cliff notes version of the History of Natural Areas and Nature Preserves in Delaware. Ahem.

In 1977, the Delaware Nature Society published the book Delaware’s Outstanding Natural Areas and their Preservation written by Lorraine Fleming. This book outlined 101 sites throughout the state that have extraordinary examples of ecological, historical, geologic, and/or cultural significance. Following the hype the book received, the Delaware General Assembly passed Delaware Code, Chapter 73: Natural Areas Preservation System in 1978. This allowed for four key things:

Since then, the Natural Areas Advisory Council and the Division of Parks and Recreation have worked together to protect over 7,000 acres of land, establishing 34 total Nature Preserves throughout the State that may or may not have public access. Phew, that was a lot. Did you get all that? Because there will be a pop quiz later….

But there was that phrase… “for future generations of Delawareans”. What does that even mean? Being from the generation between Millennials and Gen Z, I can’t even fathom what generations after Gen Z are going to look like, sound like, or what trends they will start that I will undoubtedly try to adopt as well in a sad effort to “stay hip and young”. I am sure that the people making decisions on which lands to protect back in the 80’s never possibly could have imagined the land they were protecting would one day have a 13-year-old filming a TikTok dance on one of the trails next to the then 150-year-old tulip poplar trees. But they still did it, and they did it for us “future generations” to enjoy however we wanted to.

I was curious recently about which Nature Preserve was the first and when it was dedicated. I found the Tulip Tree Woods and Freshwater Marsh Nature Preserves (both located within Brandywine Creek State Park) … and – get this – they were dedicated in 1982! I remember looking at those documents for a moment and realizing that it was their 40th Anniversary this year! How lucky is that? I immediately went into gear planning their birthday party.

On November 4th, 2022, the Brandywine Creek State Park staff, Delaware Nature Society staff, Managers of the Tree for Every Delawarean Initiative (TEDI) staff, and the past employees of the Division of Parks and Recreation who made all of this happen came together to celebrate the birthday of the Tulip Tree Woods and Freshwater Marsh Nature Preserves. The event included some joyful and appreciative speeches from Charles “Chazz” Salkin, the first Nature Preserves Manager, later Land Preservation Office Chief, and even later Director of the Division of Parks and Recreation, and Lorraine Fleming herself. Following the speeches, we planted 260 trees adjacent to the Nature Preserve to establish a new era of forest for “future generations”. This planting was funded by TEDI, Governor Carney’s plan to combat climate change by planting trees throughout the state for carbon sequestration. After a long morning of planting trees, our guests convened for lunch and shared the famous “Bobbie” from Capriotti’s Sandwich Shop. After lunch, the Brandywine Creek State Park Interpretive staff hosted a guided walk through the Tulip Tree Woods Nature Preserve to awe at the now 200-year-old poplar trees. The day was truly magical.

And so, dear reader, the point of this article is this: making conservation and preservation decisions today for “future generations of Delawareans” is a weird and abstract concept that I don’t think anyone can truly grasp. I mean, how did those key people in the 80’s truly know that their decision to protect an old growth forest like the Tulip Tree Woods Nature Preserve would result in a New Jersey native woman, who happened to land her dream job at DNREC as the Natural Areas and Nature Preserves Program Manager, becoming completely enamored with this State’s Preserves and throw them a birthday party 40 years later? Let alone, be handed to torch to continue to protect land for future generation.

With that, I wanted to say: if you are reading this and you have contributed to the preservation and protection of the State of Delaware’s outstanding piedmont, marshes, freshwater wetlands, coastal dunes, etc.: Thank You. I can only hope that I do half as good of a job as you all have these past 40-50 years and pass that on to my own next generation.

Thank you for your attention and Happy Holidays! Enjoy your time off visiting one of our 34 Nature Preserves (that has public access) throughout the State!

If you would like to know more about the Natural Areas and Nature Preserves throughout Delaware or just want to chat about what preservation work you have accomplished, please do not hesitate to reach out to me via e-mail at Melanie.Cucunato@delaware.gov or via phone at (302) 739-9039.

Written on: December 19th, 2022 in Wetland Assessments

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

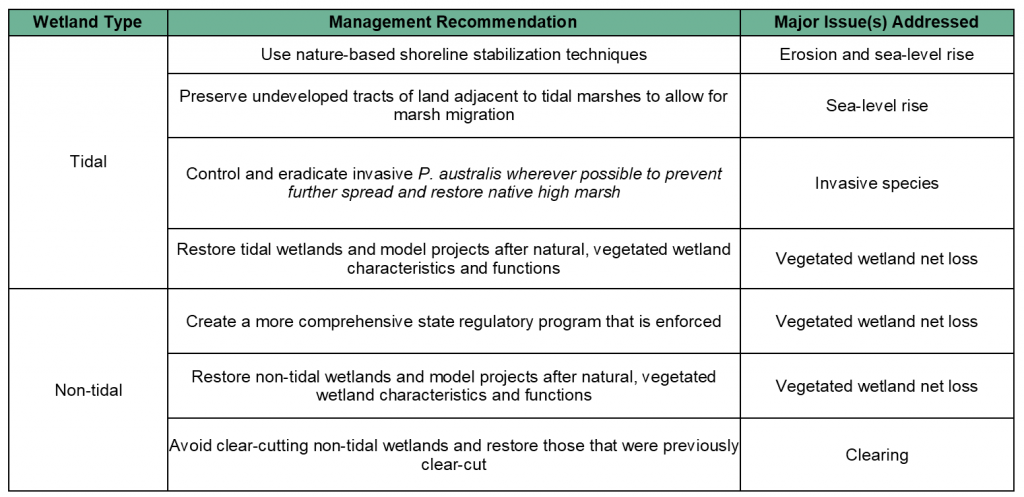

In this sixth and final installment in my Wetland Status and Trends blog series, I’m wrapping it all up with management recommendations. We came, we mapped, we calculated, we reported, now what? What comes next for wetland management and conservation in Delaware based on this project? Our recommendations stem directly back to the most prevalent causes for the recent loss of wetland acreage and function.

We offer seven main strategies for tidal and nontidal wetlands but the list could go on. You will notice that tidal wetland recommendations focus on addressing mostly natural forces such as sea level rise, subsidence and erosion. They are more innovation and capacity related areas of development. The bigger picture there is climate and consumption related Suggestions for nontidal wetlands, on the other hand, focus on limiting human impacts, making up for human impacts and prioritizing wetlands over money-making land uses.

On the tidal wetland front we are looking for more nature-based shoreline stabilization tactics to combat coastal shoreline loss. Delaware and DNREC is actively working on improving living shoreline practices and access but funding, landowner trust/perception, and technical expertise is still lacking. Next, we call for a step up in planning ahead for land conservation as sea level rise pushes marsh migration inland. Healthy wetlands can adjust themselves on the landscape to rising waters but only if natural, unhardened land awaits them, so strategic land preservation is key. Third, the war on invasive plants needs more support and more publicity. The Delaware Invasive Species Council and Senator Stephanie Hansen are helping raise awareness and encourage natives, but more aggressive and effective control of Phragmites is needed statewide. Fourth, it is important, as we document coastal wetland losses, that we have better capacity to restore tidal wetlands. Beneficial use is a complex tactic with a lot of potential to facilitate the return of eroded sediments back onto tidal wetlands. Beneficial use has not been widely demonstrated in Delaware so the legal and technical logistics are still evolving and DNREC supports more research and education.

In terms of nontidal wetlands, the recommendations are not new. The answers to our problems are us. For forty years, the documented loss of headwater forested flats has continued. As the urbanization of Delaware continues, seasonally unobvious and unregulated wetlands fall to land use changes such as timber harvesting, conversion to agriculture, and development. Our recommendation is for a comprehensive state regulatory program that also includes wetlands omitted under federal definitions. That includes effective enforcement and adequate mitigation for unavoidable impacts. Second, we want the field of wetland restoration be able to replace the wetlands being impacted and be restored in such a way that replaces wetland function. In this arena, more technical expertise, financial incentive, and landowner interest are needed. Third and final, we ask for timber harvesting to avoid nontidal wetlands, and to avoid clear-cutting. This includes recommending practices that leave the site hydrology intact and replaces vegetation with native species.

Above all, wetland conservation would benefit from better awareness, appreciation and prioritization of Delaware’s valuable resources. It’s difficult to hold back growth and gain but the long-term value of healthy functioning wetlands outweighs short term profits. DNREC is involved in moving several of these recommendations forward and we will continue working to improve wetland conservation and management through science and education, but we need help from many others.