Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube RSS Feed

Written on: May 27th, 2021 in Wetland Assessments

By Alison Rogerson, Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program (WMAP)

In March we shared some results about the status of wetland acreage in Delaware between 2007 and 2017. This time we’re taking a closer look at the increasing number of stormwater ponds popping up across the state. Is this a good trend or something to be concerned about? How do ponds relate to wetland health?

You pass stormwater ponds every day. Along State Highway Route 1, next to the shopping center parking lot, or at the entrance of your neighborhood. Stormwater ponds are ubiquitous with development and we have a lot of development in Delaware.

In fact, between 2007 and 2017 Delaware experienced an increase of 1,260 acres of man-made retention or stormwater ponds around housing developments, ponds in industrial areas, or agricultural ponds. This represents 81% of all the acres of wetlands created, or gained, in this time period. The majority of open water gains occurred in Sussex County.

What is the issue with building more stormwater ponds and what does it have to do with wetlands? It just so happens that at the same time Delaware gained 1,260 acres of open water ponds, it lost 655 acres of freshwater wetlands, mostly forested, to development. In many cases, forested freshwater wetlands were lost to development and new developments require stormwater management, often as ponds.

Unfortunately, created ponds do not function the same way natural, forested wetlands do. Man-made open water ponds offer stormwater holding capacity, but don’t offer the same filtration and slow release into natural waterways that floodplain wetlands do. Stormwater ponds can be used by generalist wildlife species such as red-winged blackbirds or mallards, but do not offer the specialized habitat qualities that Delaware’s wetlands can provide. Created ponds offer little in the way of plant community, often cattails or the invasive Phragmites, whereas natural wetlands provide a rich array of beneficial plants.

I wish I could say this trend of increasing stormwater ponds and decreasing wetlands was just a recent occurrence, but similar changes were observed in previous decades as well. According to our previous statewide mapping update and analysis done for 1992-2007, gains in ponds exceeded gains of any other wetland type by 115%.

Do we need stormwater ponds? Yes. Especially as weather patterns become more extreme, bringing heavy rain events upon us in Delaware, we need infrastructure to quickly handle flash events and heavy stormwater loads. Stormwater management keeps our roads and neighborhoods from flooding, and can prevent backups that lead to polluted waters being released.

However, it is not appropriate to replace natural wetlands with stormwater ponds in the name of development. The trade-off in functions and natural services does not add up. In addition, stormwater infrastructure has been modernized to more naturally offer storage and filtration services that are visually appealing.

Green stormwater infrastructure features can be planted with native trees and shrubs and may sit dry until a storm event. These structures are still ready and waiting to hold and manage storm events, but allow the soil and plants to play a beneficial role. Bioretention gardens are smaller features that can be incorporated into landscaping that are enjoyable to look at.

For more information on Green Stormwater Infrastructure visit this USGS webpage.

Written on: May 17th, 2021 in Wetland Restorations

By Maggie Pletta, DNREC Coastal, Climate and Energy

Delaware is known for many things… like being first, Joe Biden, and horseshoe crabs. However, there are a few less flattering things that Delaware is known for, and one is a history of polluted waterways.

A large number of Delaware’s waterbodies have a fish consumption advisory, with some of the strictest advisories in place on the tidal Christina and Brandywine Rivers. But starting in spring 2021, the DNREC Watershed Approach to Toxics Assessment and Restoration (WATAR) program is looking to change that and is embarking on an initiative to improve the waters of the Christina and Brandywine Rivers

The project is titled CBR4, which stands for “Christina & Brandywine River Remediation, Restoration, and Resilience.” The goal of the project is to address legacy toxic impacts within the watershed, and within the waterways themselves, to make the rivers drinkable, swimmable, and fishable in the shortest timeframe possible.

A Long History

The Christina and Brandywine Rivers have played a pivotal role in the region’s economy and character since before the Swedes first arrived on the original Kalmar Nyckel in 1638. The river already was part of a route of warfare and trade between the Lenape (Delaware) Indians along the Delaware River (and tributaries like the Brandywine and Christina) and the Minqua (Susquehannock) Indians on the Susquehanna River to the west. When the Swedes sailed up the Delaware River and arrived at the mouth of the Christina River in Wilmington, they found an ideal port location to ship trade goods and supplies between the colonies and Sweden. Not only did the site provide easy access to shipping channels, but it also provided access to the Brandywine, where shad and shellfish abounded. Unfortunately, like many natural resources, as more colonists arrived, the rivers slowly became polluted.

During the industrial revolution, the Christina and Brandywine riverfronts became populated by heavy industry, including shipbuilding, tanneries, and chemical factories. While these industries provided jobs for many, they also left heavy metals, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and other hazardous substances in the soil and waterways. Many of these are considered persistent, bio-accumulative, and toxic (PBT) compounds. As industries slowly shifted out of Wilmington, they left behind their toxic legacy. Neighborhoods that had developed along these rivers remained, and residents were subject to the environmental and economic impacts of this legacy.

Why now?

In the 1990s, the state and federal government began to remediate the many brownfields and superfund sites along the rivers. While there have been successes, there is still a long way to go until the rivers are swimmable, fishable, and drinkable again.

Thanks to decades of this previous work, the clean-up of many of the land-based pollutant sources have been completed, and concentrations of PBTs in the water and fish have been dropping. The time is now to begin the long planning process to clean up the waterways’ sediments while the last remaining land-based sources of pollutants are controlled.

Over the next two years, the WATAR team and the Delaware Coastal Program, Christina Conservancy, American Rivers, Brightfields Inc., Sarver Ecological, and the Delaware Nature Society will be creating a comprehensive plan to combine sediment remediation with ecological restoration/coastal resilience projects within the CBR4 project area.

Upon completion, the WATAR team will begin the more extended, arduous task of implementing the plan’s actions. While potentially complex and daunting, the team is ready and eager to lead the charge to return the Christina and Brandywine Rivers to their former glory.

For more information about CBR4, visit https://dnrec.alpha.delaware.gov/waste-hazardous/remediation/watar/.

Written on: May 17th, 2021 in Outreach

By Olivia McDonald, Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program (WMAP)

Happy American Wetlands Month!

During the month of May we celebrate the incredible importance of wetlands to the environment and humans alike. Wetlands are ranked as one of Earth’s most productive ecosystems, supporting an incredible amount of biodiversity, and are considered a nature-based solution to climate change. These ecosystems even play a vital role in our country’s economic and social health. Wetlands can be found all across the United States and can include marshes, swamps, deltas, mangroves, and floodplains, just to name a few. On a more local scale, almost anywhere you stand in Delaware puts you within one mile of a wetland. The future of our First State and its natural resources depend on the functionality and benefits wetlands provide. Listed in this blog post are reasons for the importance of better understanding and protecting these ecosystems in our community; 5 reasons to love wetlands.

1. Wetlands improve water and air quality

You can think of a wetland much like a human’s kidney, trapping and filtering pollutants before they reach a destination. Without wetlands, hazardous chemicals and harmful nutrients could enter ecosystems such as bays, rivers, and beaches regularly without any filtration or barrier. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Office of Response and Restoration, wetlands absorb 8.1 million tons of carbon dioxide each year from the atmosphere. Here in Delaware, clean water and air play a major role in ecotourism, as well as our everyday lives.

2. Wetlands support species biodiversity

The term biodiversity simply put means all the different types of life you’ll find in one area. The greater variety in a species or ecosystem, the better natural sustainability that area will have. Wetlands habitats have aquatic plants, wetland soils, and evidence of water at or near the surface, including during the growing season. With those environmental factors comes more variety of species, complex food chains, and unique plants. In turn, wetlands then provide shelter, food, breeding ground, and water for a wide diversity of flora and fauna.

3. Wetlands protect the coast and communities

Wetlands act like sponges and hold very large amounts of water over large areas. During storm events, these ecosystems capture rain and flood waters slowing movement to later release the water downstream. Wetlands also act as erosion control by stabilizing shorelines and preventing the movement of sediment. According to the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) a one-acre wetland can store 330,000 gallons of water to a depth of one foot. Protection like that against coastal flooding and erosion in Delaware critically protects our homes and property.

4. Wetlands support the economy

Whether it’s commercial seafood harvest, or recreational fishing, coastal wetlands provide habitat that create financial benefits. At WMAP we estimated that 85-95 percent of our recreationally or commercially important coastal fisheries rely on tidal wetlands as a place to shelter and grow young. Hundreds of thousands of jobs depend on these valuable ecosystems for economic stimulation. In Delaware, these wetland areas draw locals and tourists alike to contribute to a multi-million dollar outdoor economy.

5. Wetlands are good for us

We’re lucky enough to live in a time where natural beauty is never too far away. Wetland habitats are intricate landscapes, with an abundance of plants and animals, that can be in our backyard or down the street. More time outdoors in natural environments means better health and well-being. Get outside and see your local wetland. Discover for yourself all the reasons why these ecosystems are immensely special to wildlife, our communities, and our individual understanding of the world around us.

Written on: May 17th, 2021 in Wetland Assessments

By Erin Dorset, Wetland Monitoring & Assessment Program (WMAP)

Here at the Wetland Monitoring & Assessment Program (WMAP), most fieldwork is done in the Delaware Bay and Inland Bays drainage basins, where waters move east to the Delaware Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. But, in 2018, WMAP had the opportunity to perform wetland assessments in a different part of Delaware, where waters drain west instead of east in the Chester-Choptank watershed. After a very buggy summer of field assessments and a couple years of data entry, analysis, and writing, WMAP is excited to share these new wetland condition results!

The Chester-Choptank Watershed

The Chester-Choptank watershed is in western Delaware and is part of the Chesapeake Bay drainage basin. The watershed continues out of Delaware west into Maryland. It is a headwater region, meaning that many streams begin here and eventually combine with other streams to funnel water west into the Chesapeake. The watershed is dominated by agriculture, wetlands, and upland forest.

WMAP visited and graded a random sample of 76 non-tidal wetland sites. All of these wetlands were one of three main types: flats, riverine wetlands, or depressions. Just as in other watersheds, WMAP used a rapid assessment method called DERAP (Delaware Rapid Assessment Procedure) to evaluate wetland health at all sites.

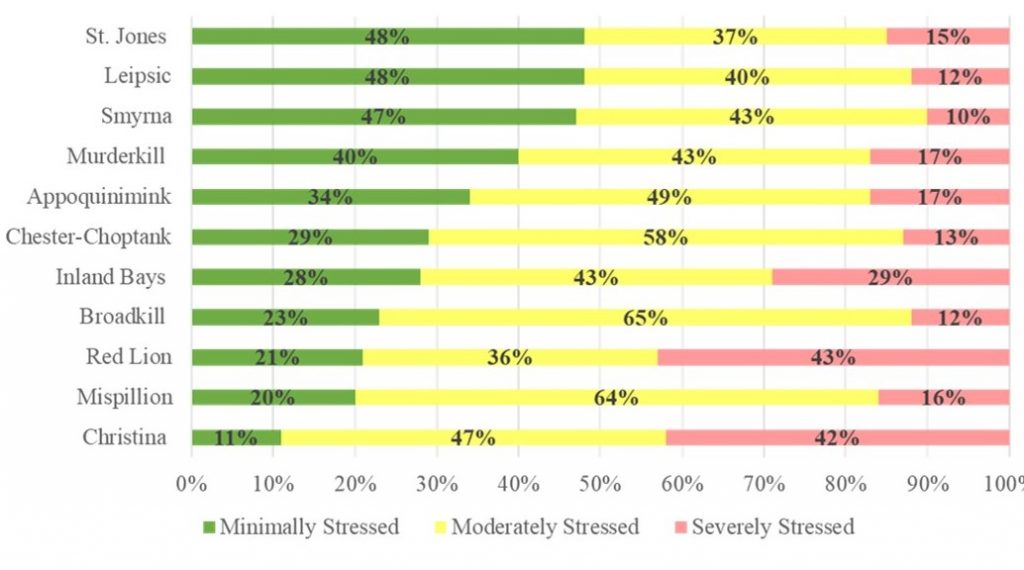

Based on that data, flat wetlands received a condition grade of B. Riverine wetlands received a B, and depressions got a B+. The overall Chester-Choptank watershed received a wetland condition letter grade of B, meaning that the watershed was doing moderately well in terms of wetland health. Compared with 10 other previously assessed watersheds, the Chester-Choptank fell right in the middle, with many of its wetlands being considered moderately stressed.

Buffer Blues

The most prevalent problems in the Chester-Choptank watershed weren’t necessarily found within wetlands but were instead often found surrounding wetlands. These problems are called buffer stressors. WMAP identified agriculture, development, roads, mowing, and channelized streams or ditches as buffer stressors that frequently occurred in the landscapes directly surrounding wetlands. Buffer stressors increase the risk of polluted runoff entering nearby wetlands, and they reduce habitat quality for wildlife.

Though buffer stressors were the most common, some other types of problems were found within the wetlands themselves. For example, invasive plant species were often present in riverine wetlands, which can crowd out native species and decrease habitat quality. Selective cut tree harvesting was a common habitat stressor in flat wetlands. Although selective cutting is not as damaging as clear-cutting trees, it can still negatively affect wetland habitat quality.

In addition, ditching was a common hydrology stressor in flats. Microtopographic alterations, such as skidder tracks from timbering vehicles and equipment, were also common hydrology stressors in flat and depression wetlands. Hydrology stressors like these can change the natural flow of water through a wetland such that plant communities, soil moisture, and groundwater levels may be negatively impacted.

Human Impacts Drive Acreage Trends

In addition to performing field assessments, WMAP used mapping data and software to explore wetland acreage trends in the Chester-Choptank watershed over time. It is estimated that the watershed lost about 39% of its historic wetland acreage by 2007 since early human settlement. Most of these losses were attributed to human development.

WMAP noticed that in recent years between 1992 and 2007, this pattern also held true, where most wetland losses were because of the construction of rural homes and housing developments. Agriculture was also a significant source of wetland loss. Most wetlands lost between 1992 and 2007 (71% of losses) were natural flats, and many natural depressions were also destroyed (23% of losses). These findings highlight the fact that most wetland losses in this watershed have been caused by direct human impacts.

Within that same 15-year time frame, some wetlands were also gained. However, most gained wetlands were ponds that were associated with human development or agriculture. Such ponds lack plants and do not resemble natural wetlands, meaning that their ability to perform beneficial wetland functions is limited. While it’s important to increase wetland acreage, it is also crucial that constructed and restored wetlands resemble natural wetlands as much as possible.

Working Together to Help Wetlands

Over half of the wetlands in the Chester-Choptank watershed were on privately-owned land. That means that private landowners can play a big role in improving the condition of wetlands in this watershed! Here are some simple ways that you can help:

Together, natural resource agencies and landowners can conserve wetland acreage and improve wetland condition in the Chester-Choptank watershed.

Want to know more about Delaware’s watersheds? Check out our web page that details the most current information about the health of wetlands on a watershed level!

You can also view and download all of our data on non-tidal wetlands, including the Chester-Choptank watershed, here.