Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: March 13th, 2020 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Restoration

By Kelly Valencik, DNREC’s Delaware Coastal Programs

Many communities throughout our state have already seen changes as a result of climate change- from shifting rainfall and storm patterns, to increased drought, to flooding from sea level rise. These consequences of the warming earth and ocean temperatures as a result of greenhouse gas emissions have brought long term community planning challenges to Delaware.

For example, residents in the City of Lewes, which sits next to the Delaware Bay in Sussex County, have noticed more and more disruptions to the typical rhythms of nature in their community. Now it’s not just the the big coastal storms or nor’easters that cause flooding issues, it is also the sunny day, strong or spring tides that are inundating sections of main roads that connect the downtown area to the major road arteries.

Other Delaware communities have experienced similar issues and and are looking for ways to tackle these problems now before they get worse, with the ultimate goal to reduce impacts to their residents.

The Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC) wants to assist municipalities and communities across the state in becoming more prepared and resilient to any change that currently appears inevitable.

Community resilience is the ability to plan for and bounce back quickly from hazardous events. In the coastal context, the focus is on planning for more frequent and stronger storms, sea level rise, and other changing climate conditions so that communities are better able to recover when the event occurs.

Communities and local governments in Delaware have the opportunity to be proactive and play a leading role in preparing and responding to the impacts of severe weather and climate change because municipalities largely have the responsibility for planning their own future through land use decisions, building codes and design, and maintenance of infrastructure such as water and wastewater systems. Using these tools, municipalities can be vigilant in protecting and safeguarding people and habitats from harm.

Green infrastructure is a nature-based approach to address environmental challenges such as stormwater runoff, coastal flooding, erosion, and water and air pollution. It uses natural processes to manage water and improve environmental quality. These natural processes include using plants and soils to:

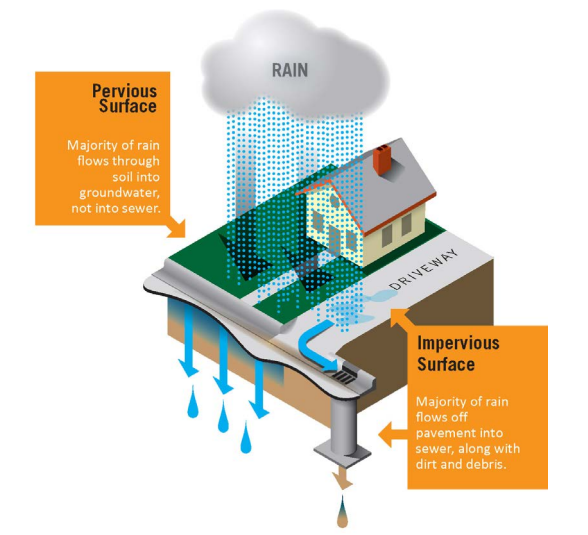

Stormwater refers to the rainwater that flows off of different surfaces after it falls to the ground. People commonly see stormwater running out of rooftop gutters and along the sides of streets during a rainstorm. The surfaces on which rainwater falls are classified into two categories:

When land is developed, pervious surfaces (water infiltrating) are replaced with impervious surfaces (solid) which allows for a larger volume of stormwater to run off into storm drains and streams. This can cause more frequent flooding and can make coastal flooding or sea level rise inundation worse. In developed areas, stormwater is also more likely to pick up pollutants like gasoline residue, animal waste, and trash and carry them into streams, bays, and the ocean.

Communities are working to improve their resiliency through the use of Best Management Practices (BMPs) to capture runoff from impervious areas, reduce flooding, and filter pollutants out of stormwater before it reaches important aquatic ecosystems, like wetlands, or recreational areas. Green infrastructure can be used in many different settings to act as a BMP that improves stormwater management and the infiltration of runoff.

For example, trees can be used in urban, suburban, and rural settings, in plantings of one or two trees, or in a 100-foot-wide forested buffer along a river shoreline. Their root systems help absorb precipitation and filter water runoff before it reaches open bodies of water. Rain gardens can act in similar way and help manage stormwater runoff from specific areas such as roofs and parking areas, while larger expanses of conserved or restored wetlands can provide flood retention, carbon storage, and wildlife habitat.

Last year the DNREC Delaware Coastal Program’s (DCP)’s Resilient Community Partnership (RCP) program worked with a group of coastal municipalities, the Cities of Lewes and Rehoboth, and the Towns of Henlopen Acres, Dewey Beach, Bethany Beach, South Bethany, and Fenwick Island, to conduct a study of impervious surface coverage. This study was done to find out what impacts the existing impervious surfaces in these cities and towns have on the stormwater management of precipitation and water quality.

These coastal communities face challenges on multiple fronts for addressing stormwater management including: tidal flooding, rapid population growth from tourism and development, a shallow groundwater table, and growing floodplain. The best path forward to consider all of these challenges to plan for their resident’s futures, was for all 7 of these communities to work together to gain an understanding of existing impervious surfaces and strategies for reducing said coverage.

Three components to this project were performed to address these multiple influences on stormwater management.

Many of the recommendations from this plan include methods of using green infrastructure at the municipal (or citywide level) and residential levels, and are now being considered for adoption in these communities. As a result, these communities are better prepared to react to address flooding and sea level rise concerns and have community specific nature-based solutions easily accessible to reduce the impact of impervious surfaces on their environment and water quality.

Written on: March 6th, 2020 in Wetland Assessments

By Catherine Medlock, Graduate Student of University of Delaware

In tidal marshes, accurate representation of marsh elevation or height is critical for understanding sea-level rise, tidal inundation, and storm surge. Small changes in marsh elevation can significantly change the water movement (hydrology), plants (vegetation), and habitat. Our study aims to look at and correct a remote sensing method known as light detection and ranging (LiDAR), in order to provide accurate elevation data to scientists and coastal managers in Delaware.

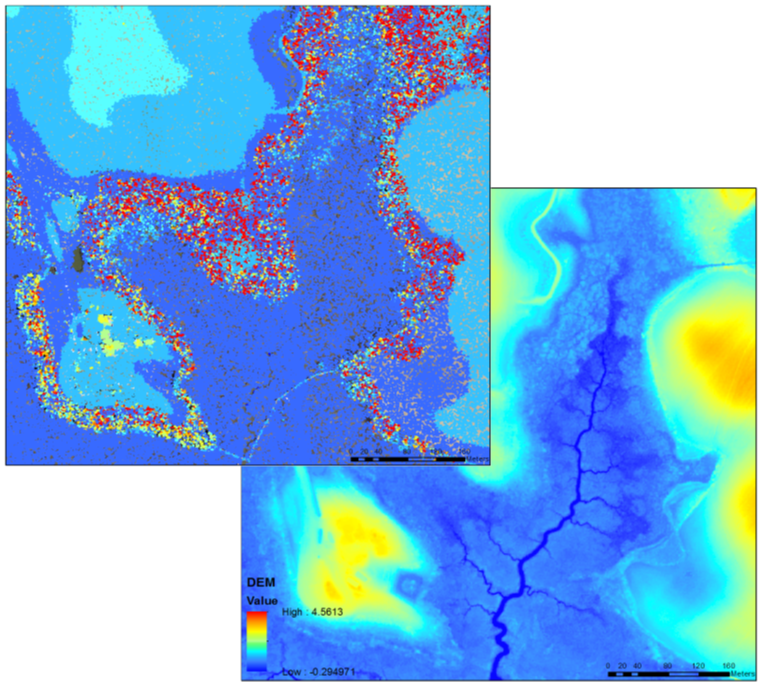

LiDAR may sound complicated, but it is really quite simple. LiDAR uses light pulses emitted from a sensor to gather 3-dimensional information about the earth’s surface. The LiDAR data is delivered as a 3-D cloud of individual points representing the ground, trees, buildings, and power lines. Ground elevation points are extracted from the point cloud, which are then used to create a digital map of the surface elevation called a digital elevation model (DEM). LiDAR is used in many coastal applications due to its high accuracy and density of data over large areas. For reference, in one square mile, LiDAR can collect over 7 million points!

LiDAR was collected across the entire state of Delaware in early 2014. LiDAR is an incredibly useful tool for topographic mapping, flood risk management, shoreline mapping, precision agriculture, and forest planning and management. Unfortunately, in tidal marshes, the light pulses are unable to penetrate through the dense vegetation to reach the marsh surface. This results in an average overestimation of 9 to 25 cm in elevation between the DEM and the actual marsh surface, depending on the marsh vegetation. This error can in turn lead to underestimations in the extent of coastal flooding and potential marsh erosion.

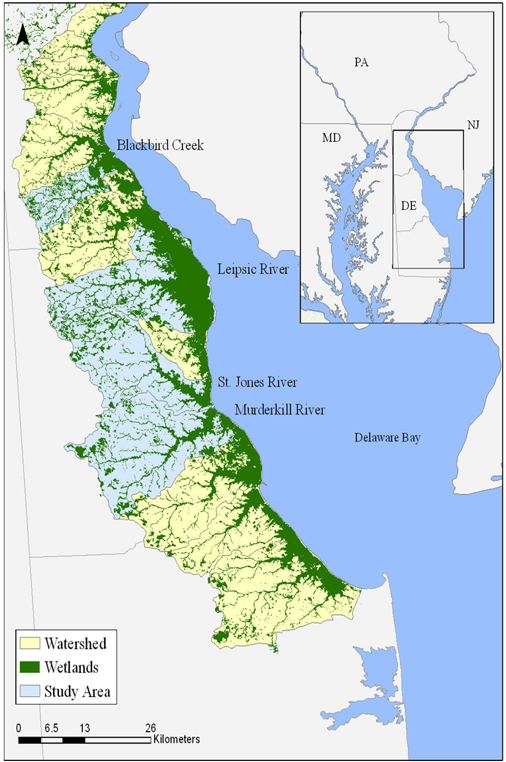

The goal of our study is to reduce the vertical error of LiDAR for mosquito ditches and the marsh platform, and provide a DEM correction that can be applied to all tidal marshes in Delaware. Four watersheds were identified to test several LiDAR correction methods: Blackbird Creek, Murderkill River, Leipsic River, and the St. Jones River. Over several years, we collected over 1000 GPS measurements with centimeter (cm)-level accuracy across the four marshes to compare DEM elevations with actual marsh elevations, and aid in the DEM corrections. As a result of the study, we plan to produce corrected DEMs, in order to model tidal inundation and assess marsh vulnerability in Delaware’s coastal marshes.

Historic human activities in marshes further complicate DEM corrections. In the 1930’s, the civilian conservation corps (CCC) dug mosquito ditches across marshes in Delaware to reduce mosquito populations by draining shallow pools on the marsh surface where mosquitoes reproduce. Enhancing drainage of the marsh surface actually transformed historically low salt marsh into high salt marsh habitat. Mosquito ditches are extensive throughout Delaware, and still visible in imagery today!

Mosquito ditches have a different elevation and vegetation than the rest of the marsh, so they require their own separate DEM correction. In efforts to correct the DEM for both the marsh platform and mosquito ditches, we hope to gain a better understanding of marsh inundation and vulnerability, and provide a useful tool to aide coastal scientists and managers in preparing for future environmental changes in Delaware’s marshes.