Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: December 1st, 2018 in Wetland Animals

By William Koth, DNREC’s Delaware State Parks

Bryozoans may be one of our most overlooked and underappreciated animals. Known as “Moss Animals,” bryozoans are small, simple animals rarely growing more than 1/25th of an inch in length. However, most bryozoans form colonies that can vary greatly in number, form, and size.

Bryozoan Biology

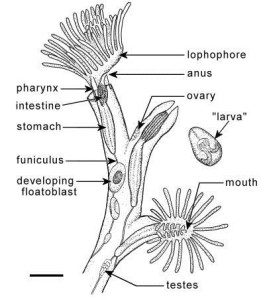

Each individual animal, or zooid, has a simple body style, usually round or oval in shape with a single opening that serves as both a mouth and an anus. Bryozoans lack any respiratory, excretory,or circulatory systems, but have a central nerve ganglion that allows the animal to respond to stimuli. They feed using small tiny ciliated (hair-like) tentacles that the surround the opening and push food through the it into the gut. In some species, and during certain life periods, these tentacles can be used for simple movement. Most species, however, spend the majority or all of their lifespan immobile.

How Many Kinds are There?

The vast majority of Bryozoan species are marine animals. Of nearly 5,000 species, less than 90 have been identified in freshwater environments, and only 24 freshwater species in North America (so far). In the freshwaters of Delaware, you are most likely to encounter the native Magnificent Bryozoan (Pectinatella magnifica). This colonial species forms jelly-like “green blobs” on underwater vegetation, branches and other structures. They may also form free floating round colonies. The small visible rosettes on the surface of the colony are groups of 12-18 individual animals.

How Do They Reproduce?

Although the Magnificent Bryozoan reproduces both sexually and asexually, the main way the colonies form is when the existing individual animal or zooid breaks away or buds asexually forming a twin. As they reproduce, they multiply into an ever growing sphere as the individuals point their mouths outwards to take advantage of available food. Meanwhile, the zooids excrete gelatinous material to give the sphere interior support.

Completely new colonies can also form asexually from small statoblasts (a group of cells encased in a hard covering to protect them from freezing or other harsh conditions). These statoblasts can float in the current, or settle to the bottom where they eventually grow into an individual zooid. These individual zooids can use their ciliated tentacles to move about in the water. They will eventually begin dividing and form a new colony. Smaller free floating colonies have been observed to use the ciliated tentacles in unison to move toward or away from stimuli.

What Do They Eat?

The Magnificent Bryozoan actively feeds on suspended organic material, zooplankton, and algae. In this way it can be considered a filter feeder and may, in some instances, increase water clarity. Individual animals on the colony are clear or opaque. It is speculated that the green color of the colonies stems from ingested algae.

Native or Invasive?

The Magnificent Bryozoan is native to Delaware, its native range extends from the Mississippi eastward to the Atlantic Coast from Ontario southward to Florida. Invasive outbreaks have been occurring in Europe since the 1930’s and west of the Mississippi since the 1950’s. The ecological impact of these invasions is still being studied, but colonies and groups of colonies have started to block some smaller waterways, ditches, and drainpipes. Colonies have been recorded up to 4 feet in Virginia, although the typical size found in Sussex County swamps, ponds and waterways is an inch to about a foot in diameter.

Encountering a colony of these animals can be a great experience. Trap Pond State Park staff receive several inquiries about these creatures each year. Most folks guess that they are some type of algae or fungus. Other guesses include freshwater jellyfish or fish eggs. Almost everyone is surprised to find out it is actually a colony of animals.

The staff recommend that you take full advantage of discovering one of these unique creatures. They do request that you not dislodge attached colonies, and not to keep them out of the water for more than a few minutes at a time. Lift it up, feel its surface, feel its weight, smell it. If you have a magnifying glass, take a look at the individual zooids on the surface. They are amazing animals that deserve a closer look and a little more appreciation!