Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: July 26th, 2023 in Natural Resources, Wetland Restoration

By Brigham Whitman, Delaware Wild Lands

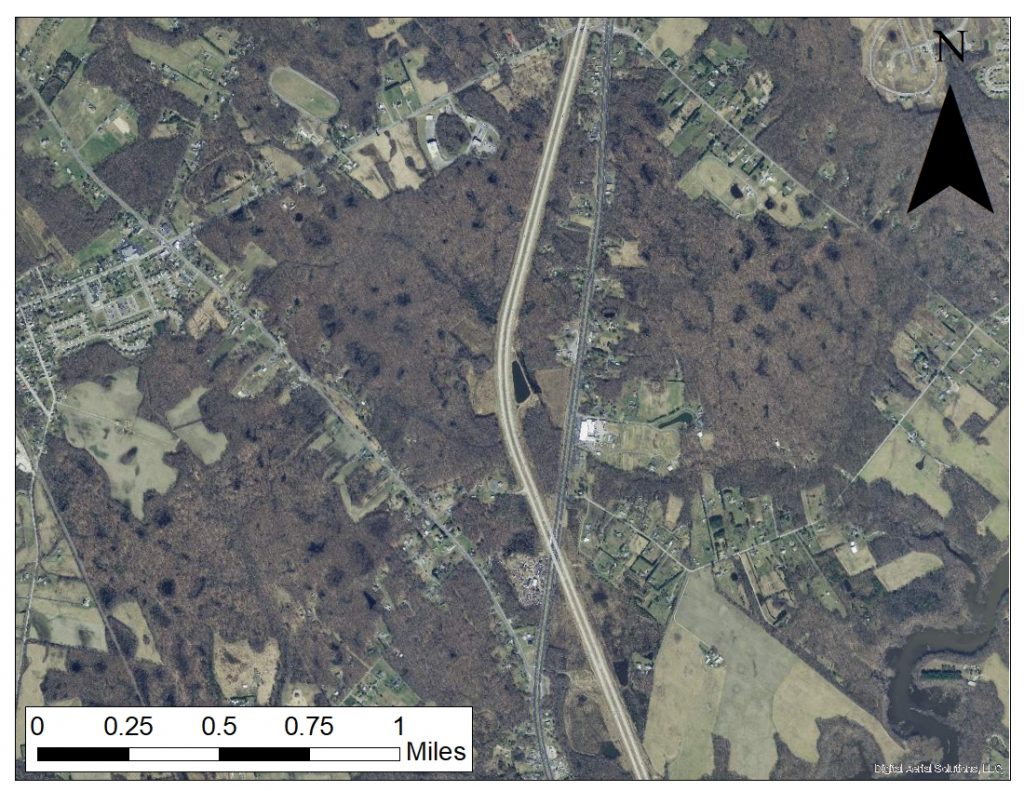

Taylors Bridge in southern New Castle County perfectly characterizes Delaware’s coastal flood plain: a mosaic of agricultural fields interspersed with patches of upland hardwood forest and the occasional residential development, surrounded by the waters of the Delaware Bay with fingers of marsh snaking throughout the adjacent low-lying areas. Aside from the natural beauty of the area, Taylors Bridge is also a highly biodiverse ecosystem, hosting 21% of the State’s flora in just 0.36% of the state’s land area. For these reasons, Delaware Wild Lands (DWL), the State’s oldest and largest land conservation organization, recently embarked on a major multi-phased effort to restore and connect natural habitats across DWL’s Taylors Bridge properties and protect the water quality of the Delaware River watershed. The first phase of this initiative, the now completed “NFWF Phase I” project, was funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) and at that point was the largest Federal grant DWL had ever received. Prior to this project, DWL typically focused on smaller grants because the organization was limited by its small staff size.

Last year, DWL and their partners, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Sarver Ecological, LLC, applied for and received a second, larger, and even more ambitious NFWF grant. In fact, this will now be the biggest Federal grant that DWL has ever received! This project, called NFWF Phase II, will rival the size and scale of DWL’s recent restoration projects at the Great Cypress Swamp in Sussex County. NFWF Phase II will add 75 acres of forest, seven acres of early successional habitat, and four acres of wetlands to the Taylors Bridge landscape. These restored areas will further connect and supplement the wildlife corridors that DWL installed in NFWF Phase I, thereby expanding the benefits of these corridors to new areas and additional wildlife populations. By utilizing a phased approach to restoration work, DWL can leverage the success of past grants to support current projects and produce results that might otherwise have seemed out of reach.

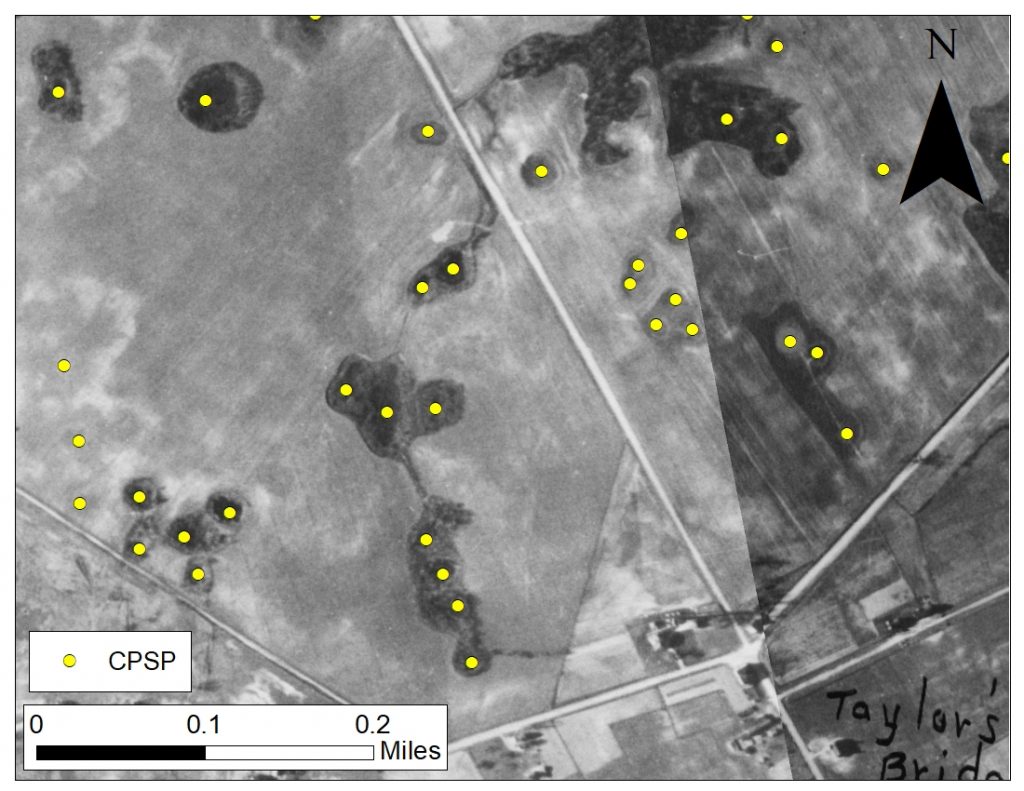

A major component of NFWF Phase II is the restoration of four acres of freshwater wetlands known as Coastal Plain Seasonal Ponds (CPSP), also called Delmarva Bays, Carolina Bays, or whale wallows. These ponds, which can be found across the eastern United States, are seasonal freshwater wetlands that are isolated from other water bodies. There are a number of theories about how these ponds formed, including meteor strikes, fish shoaling activity, or wind erosion during the Pleistocene Era. What is certain, though, is that without predatory fish, CPSP can provide unique habitat for rare and endangered species that can’t exist in other water bodies. CPSP were once a dominant feature on the landscape, and Taylors Bridge was a hotspot for these ponds. With the conversion of land for agricultural and residential use, however, many ponds were drained or filled-in. The CPSP that remain are now substantially threatened by development and sea level rise.

In preparation for the CPSP restoration, DWL staff referenced aerial imagery of DWL’s Dickinson Farm from the 1920s and performed subsurface soil investigations to determine where these ponds once existed. This year, staff will work with an excavator to restore the CPSP depressions to their original depth and place locally sourced tree stumps and logs to provide the structure necessary for a functional wetland ecosystem. DWL staff will then fill in the surrounding landscape with trees, grasses, and forbs.

Once NFWF Phases I and II are complete, the forested areas will serve as stop-over habitat for migratory songbirds and create a rare forest block in the region that will support forest interior dwelling wildlife species such as the wood thrush. The early successional habitat will benefit native bee and butterfly populations; provide habitat for snakes, turtles, red fox, opossum, skunk, and white-tailed deer; and support bird species such as the American woodcock, Baltimore oriole, indigo bunting, bobwhite quail, and turkey. The unique conditions in the CPSPs will benefit amphibians, reptiles, aquatic invertebrates, and rare insects and plants such as the state-endangered rare skipper, the amber-winged spreadwing, and the CPSP specialist plant American featherfoil. Farming activity will be streamlined as DWL makes a strategic effort to remove wet, marginal land from production in an effort to address sea level rise and manage the inland migration of marsh habitat on DWL properties. Furthermore, the trees and other vegetation that are planted will support conservation of the nearby marsh and protect the water quality of the Delaware River watershed. Landscape-scale conservation is a complex task, but DWL’s phased approach to conservation is achieving big results in Taylors Bridge.

To learn more about Delaware Wild Lands, visit dewildlands.org and follow them on Facebook and Instagram!