Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: July 22nd, 2025 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Research

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

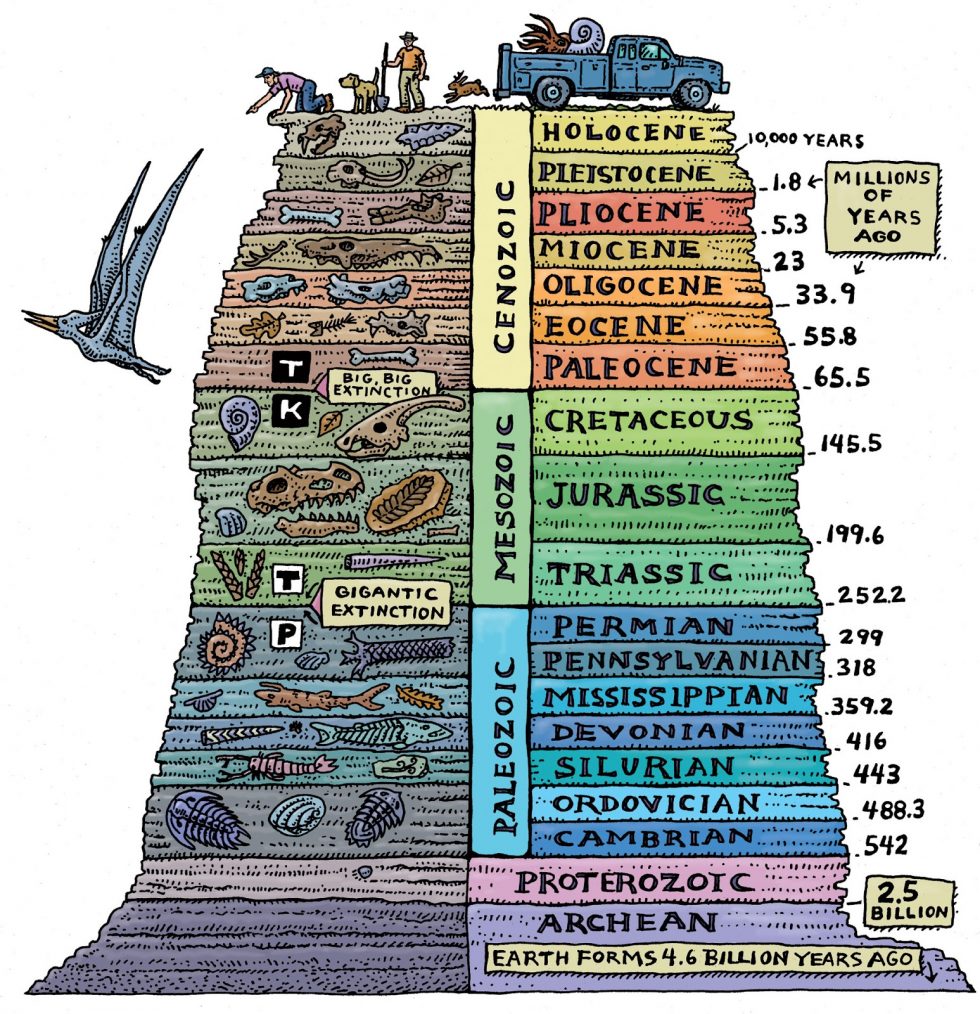

Many millions of years before us Homo sapiens appeared, there lived a vast array of plants and animals in extensive environmental systems we no longer see today. With Earth having formed 4.6 billion years ago, there are certainly a lot of eras between the cloud of dust and gas, to our modern informational age. Though we’re not paleontologists, for this blog installment we wanted to investigate the past, go way back to a time with no humans at all. Let’s venture into our prehistoric periods and discover what creatures may have lived in wetland habitats in the land before time.

Eyrops

During the Permian period, around 290 million years ago, Earth’s plates formed a single massive continent called Pangea as desert-like conditions were replaced by humid and steamy, wet environments. Queue the insects, amphibians, and therapsids (precursors of mammals) to flourish during this warm time. Eryops is one of the largest known amphibians to ever live, growing up to 7 feet long and weighing up to 440 pounds. These predatory water lovers had many sharp, coned-shaped teeth, suggesting they had a carnivorous diet of mostly aquatic tetrapods and large fish. Research shows juveniles may have lived in vast swamps for protection from land predators, while adults thrived in lowland bank habitats in and around ponds, streams, and rivers. Oddly enough, its fossils have been found in some of the driest North American areas such as Texas and New Mexico.

Deinocheirus

Moving on to a quite bizarre looking pot-bellied dinosaur with clawed hands, a humped back, and a beaked head with no teeth. Meet the Deinocheirus. This creature lived in modern-day Asia during the late Cretaceous period around 70 million years ago and clocked in at roughly 15,000 pounds and 40 feet high. But this colossal beast was more of a gentle giant. Based on fossils and their location – what is now Mongolia – scientists believe that this dinosaur was mostly an herbivore feeding on soft plants at the bottom of rivers and lakes but occasionally would snag fish and small invertebrates, hence their lack of teeth. With warm, shallow waterbodies and vegetated floodplains abundant, the Deinocheirus used its hooked claws to grasp vegetation and broad beak to suck up food. Its bone structure and lack of pinched toes suggests it moved at a slow pace, wading through wetlands for the next snack and protection from top predators like the Tyrannosaurs. We think the little tufts of arm and head feathers are its most notable feature.

Meganisoptera

Now, we take to the sky. Being the earliest flying insects know, meganisoptera, or griffinflies, were alive during the Carboniferous period about 299 to 359 million years ago and grew to a variety of enormous sizes. With wingspans from 8 inches to 2.5 feet in length, these giants had wide wings with a massive network of veins and spined appendages for holding prey. Meganisoptera enjoyed humid wetlands near freshwater and were carnivorous predators, hunting in-flight for smaller amphibians and insects, even tiny mammals! Like our present-day dragonflies and damselflies, having wings gives you a massive advantage when it comes to survival – you can cross obstacles such as water, access more food, and escape predators quickly. Though there is some debate, many scientists believe there was a massive influx in global oxygen levels during the Carboniferous period which allowed many land-living invertebrates to get to huge sizes. Give meganeura or meganeuropsis a Google to see just how big we’re talking.

Asteriornis

This creature lived right before Earth really changed. About 700,000 years before the Cretaceous-tertiary extinction wiped out about 50% of plants and animals and all non-avian dinosaurs, there lived the Asteriornis. Not only is it considered one of the earliest waterfowl ancestors, but fossils discovered in 2020 indicate it could be the earliest known ancestor of every chicken and duck on the planet. Woah. Waddling along the shores of modern-day Europe with subtropical marine climates, this long-legged creature most likely could fly and was roughly the size of a quail. Though small, the shape of their legs and beak suggests they were well adapted to shoreline habitats and potentially omnivores, plucking and dipping for food along the coast. Also known as the “Wonderchicken”, paleontologists and bird researchers continue to look for evidence of this early avian species, as it may help fill gaps in the origins of bird diversity.

We understand that prehistoric wetland habitats were not the same as they are today. But wetlands have a long geologic history on our planet, and in some instances, have dramatically impacted the Earth’s environments. Studies have shown that wetlands started shaping pathways of change as early as the Paleozoic era through the evolution of algae and land plants. So, though the flora and fauna that inhabited prehistoric habitats were far different, as wetlands evolved, so did their many critical functions and links to Earth’s cycles. It’s difficult to wrap our heads around a Devonian marsh plant or oceans filled with massive killer reptiles like the Plesiosaurs because history is one of the most challenging things to interpret. But in our current times of climate instability, looking at past species and ecosystems can allow us to understand how current ones may respond to large scale changes on our planet. Hopefully this blog post inspires you to look up other creatures of ancient habitats, dig into wetland history in America, or even investigate the geologic timeline of Delaware. If anything, surely this got you in the spirit for the new Jurassic World: Rebirth movie.

One of the best things about science is that there is always room to discover more.

Written on: July 22nd, 2025 in Natural Resources

By Alison Stouffer, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Congratulations folks! You have made it to the fifth, and final, installment of the cross-country wetland road trip. I would be lying if I said this wasn’t a bittersweet moment. I am excited to explore what the Northeast United States has to offer, but sad to say goodbye to all the fictional memories we have made together and hours we have spent in the car. As always, you can read up on the previous one, two, three, and four excursions on our blog.

Encompassing both the Atlantic coastal plain and the Appalachian Highlands, the landscape ranges from low-lying, flat topography typically along the coastline to forested hills and mountains as you move inland. This mountain range helps contain moist air from the ocean over the region, contributing to ample rainfall. Unlike other regions visited during this trip, the Northeast is not known for any particular wetland type. The topography and climate vary from state to state and might contribute to this image. Whatever the case may be, the lack of information hinders my introduction writing; so, let’s jump right in!

Delaware

It seems only fair that we begin our final road-trip with the First State! Now, I will admit, picking one wetland point-of-interest for our home state was quite difficult when there are so many places to choose from. However, the road trip must go on; so, to Brandywine Creek State Park we go. This location was picked in order to highlight a rare wetland type in Delaware, seep wetlands. Seeps are small, non-tidal wetlands fed by groundwater that seeps out onto the surface or base of a slope. They provide significant local ecological value as they are Category One wetlands.

Maryland

Our next stop takes us across the Chesapeake Bay to Jug Bay Wetland Sanctuary in Maryland. Located on the Patuxent River, the Sanctuary protects 1,700 acres of land across six properties. The Sanctuary encompasses freshwater wetlands such as tidal freshwater marshes – many of which are dominated by wild rice – and forested wetlands. As a sanctuary, Jug Bay balances the need for public recreation, scientific exploration, natural resource protection, and education to ensure maximum protection of wetlands. During your visit, enjoy the scenery, take a hike, view some birds, go for a paddle, or test your plant identification skills.

Pennsylvania

Moving north, we will be journeying to another freshwater wetland called Spruce Flats Bog in Forbes State Forest. This 28-acre wetland is unique in its elevation, having formed in a mountaintop depression. Not only is its elevation unique, but it has had quite the lifecycle! Spruce Flats Bog – over thousands of years – filled in, became meadowland, and then hemlock forest. The forest was then harvested around 1900, leaving the area to revert bag to a bog. Today, the bog continues to accumulate peat and fill with decaying plant matter, in the future returning to its meadow stage.

New Jersey

From freshwater to salt, our journey takes us to Edwin B. Forsythe National Wildlife Refuge. Spanning 48,000 acres, 82% of the refuge is wetlands, which act as a crucial stopover point for birds migrating along the Atlantic Flyway. Fun fact: the impoundment – a manmade structure that creates habitat for waterfowl and other birds through the control of water levels – seen today at the refuge was a historic railroad that cut through the marsh and was later destroyed by a storm and scrapped for metal during WWI and WWII. Along with birdwatching, visitors can experience the vast salt marshes of the refuge by foot, car, boat, or bicycle!

New York

Our next stop is a bit of a unique one as it was formerly the largest landfill in the world. Freshkills Park is a 2,200-acre park that is currently in development on Staten Island. Part of the plans include restoring 360 acres of tidal wetlands that had previously filled in to support development and a growing population. Before its time as a landfill, the area was home to the Lenape people, who relied on the wetlands for sustenance. After Dutch settlement, the land was then cultivated for salt hay, which fed horses transporting 17th century New Yorkers around the growing city. While pre-restoration scientific monitoring is currently taking place, visitors can kayak the Arthur Kill and connecting waterways that wind past and into the area, ultimately connecting to the William T. Davis Wildlife Refuge.

Connecticut

Continuing with the trend of tidal wetlands, we are headed north to the Connecticut National Estuary Research Reserve, which encompasses areas along the Connecticut River, Thames River, and Long Island Sound. Not only does the Reserve protect tidal saltwater and brackish wetlands, but it also includes submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) and shellfish beds – which are important natural resources that go together with wetlands. For example, these habitats can provide a safe place for breeding and feeding, in turn supporting a diversity of fish species – so much so that the Connecticut River (with 78 species of fish) has the highest diversity in the region!

Rhode Island

A short distance to the east is Rhode Island, the smallest state in the country – it even has Delaware beat! Swamp wetlands are the most common types found within the state. Our next stop, the Great Swamp Management Area is an example of this type of wetland, and is even one of the largest contiguous swamps in Rhode Island. Managed by the State’s Department of Environmental Management, the area encompasses 2,200 acres of pristine cedar and red maple swampland.

Massachusetts

Our next wetland stop has us pahk the cah at the Boston Hahbah. From there, we will be taking a ferry ride to the 34 islands that make up the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area. Each island is different and offers a unique wetland perspective. Some islands have marine intertidal and subtidal wetlands along their shorelines, which are exposed to the open ocean. Some islands have estuarine wetlands, which have some protection against the waves of the open ocean but experience tides from the Harbor. Finally, some islands have rare palustrine, or freshwater, wetlands. These are primarily seasonal vernal pools. Some islands even have any combination of these three wetland types.

Vermont

Like Delaware’s Category I wetlands, Vermont designates irreplaceable wetlands of exceptional ecological value as Class I wetlands, which is given the highest level of protection. While there are currently 11 designated Class I wetlands, we will be visiting The Nature Conservancy’s LaPlatte River Marsh Natural Area. This Class I wetland is a 205-acre floodplain of the LaPlatte River, filtering pollutants out of the water from the surrounding area before flowing into Lake Champlain. While enjoying the area – either by foot or by paddle craft – you will be able to see freshwater riverine wetlands, cattail marsh, black ash seepage swamp, and bottomland forested wetlands to name a few. If you’re lucky, you might spot a beaver gnawing on a tree, contributing to the wetland landscape. Explore more Class I wetlands here!

New Hampshire

Like Vermont, our New Hampshire wetland stop is another property owned by The Nature Conservancy. We will be visiting the universally accessible Manchester Cedar Swamp Preserve. What do I mean by “universally accessible”? Well, let me tell you. TNC believes in equitable access to nature for all and has created a trail that is accessible to visitors with varying comfort levels and abilities. The trail and boardwalk are ADA-compliant, and interpretation is available in audio format in both English and Spanish. Visitors can view black gum and Atlantic white cedar trees – one of the rarest wetland types in the state – along with giant rhododendron right from the trail!

Maine

Last, but not least, we will be heading to a place I hold near-and-dear to my heart – it’s where I got my start in the field of wetland science – Rachel Carson National Wildlife Refuge. The Refuge consists of 11 parcels that protect important salt marsh ecosystems, among other types of habitats. This is especially important for the salt marsh sparrow, which relies exclusively on these habitats. Researchers at the Refuge focus on conserving and protecting critical habitat, managing and controlling invasive species, including Phragmites australis, piloting wetland restoration techniques, monitoring surface elevation and vegetation, and protecting threatened migratory birds like the piping plover.

Next Stop: The End

With that, we come to the sad end of our Cross-Country Wetland Road Trip. It has been a long journey we have traveled together over the months, but I know I have learned a lot about the different types of wetlands and what they look like state-to-state. I hope you have too. While my writing might have transported you to each and every location as if you were truly there (a girl can dream), be sure to consider making a stop if you do ever happen to be in the area of any of these wonderful wetlands! I know I will be. Until we meet again, enjoy Googling wetlands across the country, explore a local watering hole, and do your part to protect and promote these magnificent ecosystems.

Written on: July 22nd, 2025 in Natural Resources, Wetland Restoration

By Kristen Travers, Delaware Nature Society

We’re all uncomfortably aware of how hot this summer has been. On a recent 90+ degree afternoon, while walking with a group of people, the first request was simple: “Let’s head to the stream in the shade.” As we stepped under the tree canopy along the streambank, the temperature change was noticeable. That welcome relief wasn’t just for us – this natural cooling is also critical for the ecosystems that rely on healthy streams.

Historically, much of Delaware was blanketed in forests, and the streams and rivers flowing through them were shaded by the protective cover of trees. These forested streamside areas – called riparian buffers – are transitional zones between land and water. They naturally cool the air and water, reduce erosion, and provide vital habitat. This cooling is essential, as many aquatic species – fish, amphibians, and insects – depend on cooler water to survive. Without shade, stream temperatures rise, and oxygen levels fall, making survival tough for fish and other aquatic life.

But the benefits of riparian buffers extend beyond temperature regulation. Leaves, branches, and other organic materials that fall into streams from adjacent trees provide essential food and shelter for aquatic organisms. These natural inputs support a complex web of life, from tiny invertebrates and fish to birds.

Small streams – often overlooked – are critical parts of this system. Like capillaries in a circulatory system, they connect to larger creeks, rivers, and eventually to the bays. As Delaware’s landscape becomes more fragmented by human activity, riparian buffers take on another crucial role: connectivity. These green corridors link waterways and habitats, enabling wildlife to move across the landscape. This connectivity is vital for maintaining biodiversity, protecting water quality, and building resilience in the face of habitat loss and climate change.

Buffers for Mitigation and Resilience

Riparian buffers also offer powerful benefits to people. By slowing stormwater runoff, filtering pollutants, and stabilizing streambanks, buffers reduce flooding risk and improve water quality – especially important in flood-prone and urban areas. Wider buffers provide more ecological and protective benefits. Ideally, buffers should be at least 75 feet wide, but even a few rows of trees can help. Where scenic views are a concern, planting native shrubs and perennials can preserve “view windows” while still providing benefits.

Getting Started with Riparian Buffers

Whether you’re managing a farm, caring for a community open space, or restoring a backyard stream, it’s never too late to establish or improve a riparian buffer. But planting trees and walking away rarely leads to success. Thoughtful planning and follow-up care are essential. Here are a few considerations:

Small Effort, Big Impact

Establishing a riparian buffer takes time and care, but with a little TLC it’s one of the most effective, low-cost strategies for improving water quality, enhancing wildlife habitat, and creating beautiful natural spaces to enjoy. As our climate changes and development continues, protecting and restoring these streamside forests isn’t just a nice idea – it’s a smart, natural investment in Delaware’s future.

Looking for more information on riparian buffers? Check out the resources below