Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: September 16th, 2024 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Research

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

As our landscape continues to change due to development and urbanization, and the impacts from climate change are ever increasing, we must adapt our ways of managing natural resources. The last generation of environmentalists (we’re talking Clean Water Act days) did a great job with point source pollution, habitat management, and pesticide control. In our current generation, ecological restoration of our already degraded systems and management adaptation are at the forefront of movement to maintain our environment. Though our love for natural wetlands runs deep, we wanted to showcase a more avant-garde management tool gaining popularity, floating wetlands. You certainly won’t find this type of wetland on the Cowardin classification system.

What are Floating Wetlands?

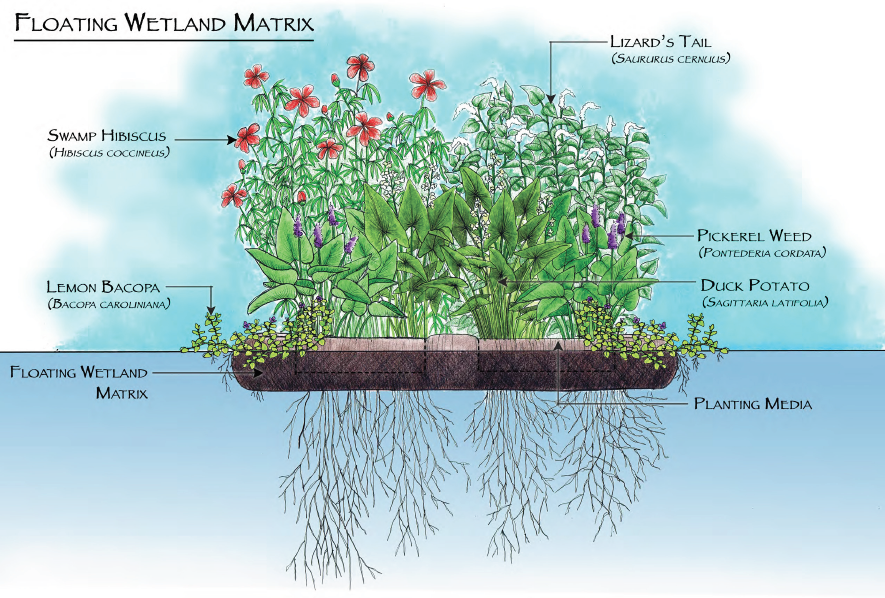

Well, the name really does say it all. Essentially, floating wetlands are tiny ecosystems created on top of a buoyant surface, then placed out into an aquatic habitat. A main component of this type of green infrastructure is that they are artificially made. The base is an artificial buoyant platform, something that can float, that is then planted with vegetation. The vegetation is primarily emergent wetland plants, meaning that the roots are tolerant of standing water and their leaves, stems, and flowers are above the water’s surface. It’s ideal that the plant species are native to the area or project region, but that doesn’t always have to be the case. Once it is complete, the platform is anchored in the water but still has enough slack to adjust to changing water levels. Your floating oasis awaits!

Benefits of Floating Wetlands

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Floating wetlands are designed to mimic the processes and ecosystem services that natural wetlands provide. It’s kind of a no-brainer when you’re using the exact plants, water, and growing conditions as a natural wetland habitat. Floating wetlands can be placed in tidal and nontidal waterways, but tidal habitat parameters can be a little trickier to work with. Let’s look at some of the benefits and advantages of floating wetlands.

Of course, every project is different. The range of benefits floating wetlands provide depend on the aquatic environment they’re placed in, type of pollution in the area, plant species used, goals and partners of the project, and the size of the structure itself. Identifying challenges and lessons learned are certainly part of any good project as well. From grant-based research to watershed management plans, as more floating wetlands are implemented the understanding of their usefulness will continue to grow.

Example Projects

It’s time to see some of these in action. The National Aquarium in Baltimore was the first place in the U.S. to test floating wetlands in a tidal system and today has over 10,000 square feet of recreated salt marsh habitat. Starting their work in 2010, the aquarium went through trial and error while navigating how to maintain a tidal floating marsh. By mimicking a habitat that once existed in the city of Baltimore, the Harbor Wetland provides green infrastructure that promotes healthy water, attracts native species like herons and American eels, and teaches visitors about wetland ecosystems. This innovative outdoor exhibit is currently open the public right next to the entrance of the National Aquarium.

Work done by the University of Washington’s Green Futures Research and Design Lab incorporated floating wetlands into a living shoreline project. The Sweetgrass Living Shoreline Restoration Project examined the benefit of floating wetlands as missing habitat on an urbanized shoreline for out-migrating juvenile salmon in the freshwater Lake Washington Basin. The floating wetlands were installed in conjunction with a living shoreline prototype and monitored for plant health, fish use, and water quality. Not only did the project provide scientific research to the lab but created educational opportunities to local indigenous youth.

Our friends over at Princeton Hydro have been into floating wetlands for quite some time now. Back in 2012 Lake Hopatcong, New Jersey’s largest lake, became the first public lake to install floating wetlands to reduce pollutant loading plus address invasive aquatic plants and nuisance algal blooms. After much success, more were installed in the summer of 2022 with help from staff and volunteers from the Lake Hopatcong Foundation and Lake Hopatcong Commission. As part of a series of water quality initiatives funded by NJDEP, these floating wetlands not only showcase project longevity but community engagement in environmental efforts.

The future of floating wetlands is bright as more research and implementation occurs in the U.S. and beyond. What can we learn from the microbial communities associated with these structures? How can we utilize them to attract specific pollinators in particular areas? Can floating wetlands compel cities to take a more aggressive approach to green stormwater infrastructure? Much like a garden, natural resource management takes tending, time, and consideration on how you want to treat the environment. The good thing about floating wetlands is that they’re a garden you won’t have to water.