Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: September 16th, 2024 in Natural Resources

By Alison Stouffer, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Welcome back to the second installment of the WMAP cross country road trip! To our returning adventurers, we are so glad you have decided to join us on the next leg of the trip. For those of you joining us for the first time, we are slowly making our way across the country as we explore a new wetland in each state of the US. If you are feeling like you missed out, you can read up about the first excursion here. Otherwise, sit back, relax, and enjoy passenger princess treatment from the comfort of your home as we head to the wetlands of the southwestern United States.

This region of the country is dominated by arid desert lands, pock-marked by low-lying basins and small mountain ranges. However, desert isn’t the only ecosystem found here; forested mountains, great plains, and intertidal coastline are also present. And throughout, wetlands (covering approximately 8% of the four southwest states1) provide a refuge for wildlife to beat the dry climate. On this leg of our cross-country road trip, we will be exploring wetland points-of-interest from Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma.

Arizona

I hope you packed your portable, battery-operated fan because the first stop of our Southwest road trip is a hot one! Tres Rios, a wetland and riparian restoration project within the City of Phoenix, is a 700-acre freshwater wetland habitat influenced by the Salt River. This demonstration site helps to re-establish the historic wetland function of the Salt River by increasing flood control within the area and removing the invasive salt cedar tree (which has pushed out native plant species like the mesquite tree). Plus, as an added bonus, Tres Rios helps filter water entering the river from the city, including reclaimed water from a nearby wastewater treatment plant.

New Mexico

From one capital to the next, we continue our journey to the outskirts of Santa Fe, New Mexico. The Leonora Curtin Wetland Preserve is a unique and rare wetland type called a ciénega, or “marsh” in Spanish, which forms around a natural spring. The 35-acre preserve is actively monitored to ensure visitation and management efforts (such as the removal of invasive plant species) are having a minimal negative effect on the habitat. This desert oasis provides critical habitat and water resources for many species of birds, butterflies, and mammals.

Texas

Our next wetland stop-over has us leaving the desert behind for Big Thicket National Preserve, which boasts over 35,000 acres of mapped wetlands! Located in a unique transition point between ecosystems, the preserve contains a range of wetland habitats, including pine savannahs with poorly draining soils, riverine floodplains that experience seasonal flooding, baygall depressions dominated by sweetbay magnolia and gallberry holly, palmetto hardwood flats where ponding can occur, and cypress sloughs that are the quintessential image of a swamp. With sea level rise, Big Thicket will likely experience a shift from freshwater to estuarine wetlands as saltwater moves inland from the Gulf of Mexico.

Oklahoma

We will be finishing the southwest portion of our wetland cross country road trip at Red Slough Wildlife Management Area in Oklahoma. Red Slough contains around 2,400 acres of wetlands, a small proportion of its historic footprint. Agricultural draining and clearing in the 1960s significantly impacted the ecological functioning of the area, which was later restored by re-establishing former hydrologic conditions. Visitors will enjoy views of mudflats, shallow-water impoundments, emergent marshes, wet prairies, riparian zones, and scrub-shrub habitats.

Next Stop: Wetlands of the Midwest

I hope you enjoyed this installment of our cross-country road trip and all the unique features the wetlands of the Southwest had to offer! We will be turning our travels north to the Midwest in the next portion of our journey so be sure to stay tuned. Until then, rest up, stretch out those legs, and start planning your return to these wonderful southwestern wetlands!

Written on: September 16th, 2024 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Research

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

As our landscape continues to change due to development and urbanization, and the impacts from climate change are ever increasing, we must adapt our ways of managing natural resources. The last generation of environmentalists (we’re talking Clean Water Act days) did a great job with point source pollution, habitat management, and pesticide control. In our current generation, ecological restoration of our already degraded systems and management adaptation are at the forefront of movement to maintain our environment. Though our love for natural wetlands runs deep, we wanted to showcase a more avant-garde management tool gaining popularity, floating wetlands. You certainly won’t find this type of wetland on the Cowardin classification system.

What are Floating Wetlands?

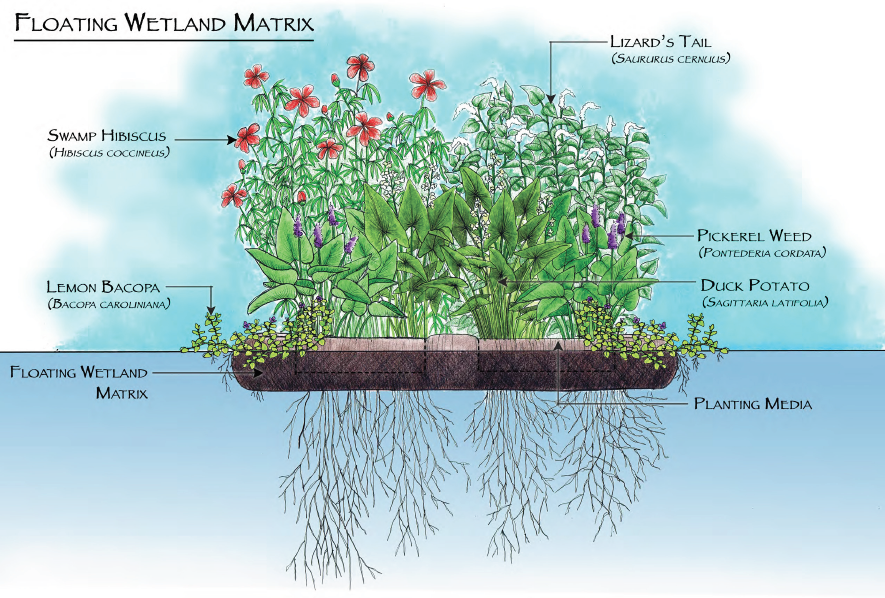

Well, the name really does say it all. Essentially, floating wetlands are tiny ecosystems created on top of a buoyant surface, then placed out into an aquatic habitat. A main component of this type of green infrastructure is that they are artificially made. The base is an artificial buoyant platform, something that can float, that is then planted with vegetation. The vegetation is primarily emergent wetland plants, meaning that the roots are tolerant of standing water and their leaves, stems, and flowers are above the water’s surface. It’s ideal that the plant species are native to the area or project region, but that doesn’t always have to be the case. Once it is complete, the platform is anchored in the water but still has enough slack to adjust to changing water levels. Your floating oasis awaits!

Benefits of Floating Wetlands

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Floating wetlands are designed to mimic the processes and ecosystem services that natural wetlands provide. It’s kind of a no-brainer when you’re using the exact plants, water, and growing conditions as a natural wetland habitat. Floating wetlands can be placed in tidal and nontidal waterways, but tidal habitat parameters can be a little trickier to work with. Let’s look at some of the benefits and advantages of floating wetlands.

Of course, every project is different. The range of benefits floating wetlands provide depend on the aquatic environment they’re placed in, type of pollution in the area, plant species used, goals and partners of the project, and the size of the structure itself. Identifying challenges and lessons learned are certainly part of any good project as well. From grant-based research to watershed management plans, as more floating wetlands are implemented the understanding of their usefulness will continue to grow.

Example Projects

It’s time to see some of these in action. The National Aquarium in Baltimore was the first place in the U.S. to test floating wetlands in a tidal system and today has over 10,000 square feet of recreated salt marsh habitat. Starting their work in 2010, the aquarium went through trial and error while navigating how to maintain a tidal floating marsh. By mimicking a habitat that once existed in the city of Baltimore, the Harbor Wetland provides green infrastructure that promotes healthy water, attracts native species like herons and American eels, and teaches visitors about wetland ecosystems. This innovative outdoor exhibit is currently open the public right next to the entrance of the National Aquarium.

Work done by the University of Washington’s Green Futures Research and Design Lab incorporated floating wetlands into a living shoreline project. The Sweetgrass Living Shoreline Restoration Project examined the benefit of floating wetlands as missing habitat on an urbanized shoreline for out-migrating juvenile salmon in the freshwater Lake Washington Basin. The floating wetlands were installed in conjunction with a living shoreline prototype and monitored for plant health, fish use, and water quality. Not only did the project provide scientific research to the lab but created educational opportunities to local indigenous youth.

Our friends over at Princeton Hydro have been into floating wetlands for quite some time now. Back in 2012 Lake Hopatcong, New Jersey’s largest lake, became the first public lake to install floating wetlands to reduce pollutant loading plus address invasive aquatic plants and nuisance algal blooms. After much success, more were installed in the summer of 2022 with help from staff and volunteers from the Lake Hopatcong Foundation and Lake Hopatcong Commission. As part of a series of water quality initiatives funded by NJDEP, these floating wetlands not only showcase project longevity but community engagement in environmental efforts.

The future of floating wetlands is bright as more research and implementation occurs in the U.S. and beyond. What can we learn from the microbial communities associated with these structures? How can we utilize them to attract specific pollinators in particular areas? Can floating wetlands compel cities to take a more aggressive approach to green stormwater infrastructure? Much like a garden, natural resource management takes tending, time, and consideration on how you want to treat the environment. The good thing about floating wetlands is that they’re a garden you won’t have to water.

Written on: September 16th, 2024 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Research

By Elizabeth Long, Delaware Sea Grant

Hi everybody! My name is Elizabeth Long, and for the past few months I have been working with Delaware Sea Grant as their Marine Debris intern! I graduated from Muhlenberg College in 2021 with a BS degree in Biology. After graduation, I moved out to Catalina Island off the coast of Southern California and worked as an outdoor educator. After leaving California, I was hoping to move back to the east coast, and was lucky enough to be given the opportunity to work with Delaware Sea Grant under their Coastal Ecology Specialist, Brittany Haywood. This was definitely a summer of learning!

The purpose of my internship was to investigate the problem of derelict crab pots in the Delaware Inland Bays. I grew up crabbing at the Jersey shore, but prior to this internship, had no idea that derelict crab pots were such a big problem, not only here, but in crab fisheries worldwide. Derelict crab pots are pots that have been abandoned or lost, usually through boat strikes, storms, or vandalism. A huge part of the problem created by these discarded pots is that they continue to trap organisms, known as “ghost fishing”. In blue crab fisheries, the most commonly ghost fished organisms are crabs, diamondback terrapins, and fish. Despite being a recreation-only fishery, it’s estimated that there are over 30,000 derelict crab pots in the Delaware Inland Bays. It’s definitely worth reading up on ghost fishing in the Inland Bays, so gather some background information on another guest blog feature from Delaware Sea Grant.

I personally became very interested in ways to reduce ghost fishing once pots have become lost. Currently, Delaware requires bycatch reduction devices (BRDs), also known as turtle excluder devices (TEDs) to be installed on all funnel entrances of a commercial-style crab pot. While not required, it is also strongly recommended to have cull rings installed on your trap, which allow for the escape of undersized crabs and small fish. I’m currently wrapping up my internship with a research project to test whether crabs have a preference as to the location of escape options in crab pots. This work could hopefully inform decisions about where escape panels or cull rings should be located should they become required in Delaware!

I also had the opportunity to help out with Delaware Sea Grant’s crab pot refurbishment workshops. The purpose of these events is to provide community members the opportunity to learn how to fix up their old or broken crab pots, and to learn about crabbing in Delaware. Locals bring their pots, and we show them how to install bycatch reductions devices, cull rings, and new line and bungees. These events always bring out people excited to learn. If you have a crab pot that needs a little love, the next refurbishment workshop is on September 27th at the Marina at Peppers Creek in Dagsboro, Delaware.

Other exciting moments from this summer included opportunities to help out in the field! First, I got to assist the Delaware Center for the Inland Bays with widgeon grass seed planting for a restoration project. I also assisted the DNREC Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program with annual transect monitoring of marsh health by looking at vegetation composition, elevation, and herbivory. These days in the field were hot and muddy, but super rewarding! It was great to get hands-on experience with the awesome work happening around the Inland Bays. Overall, I had an awesome summer working with Delaware Sea Grant and am looking forward to whatever comes next!

Looking to find out more about Delaware Sea Grant and their partners in the environmental world? Join us all at the University of Delaware’s Coast Day on Sunday, October 6th!