Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: September 22nd, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Natural Resources

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

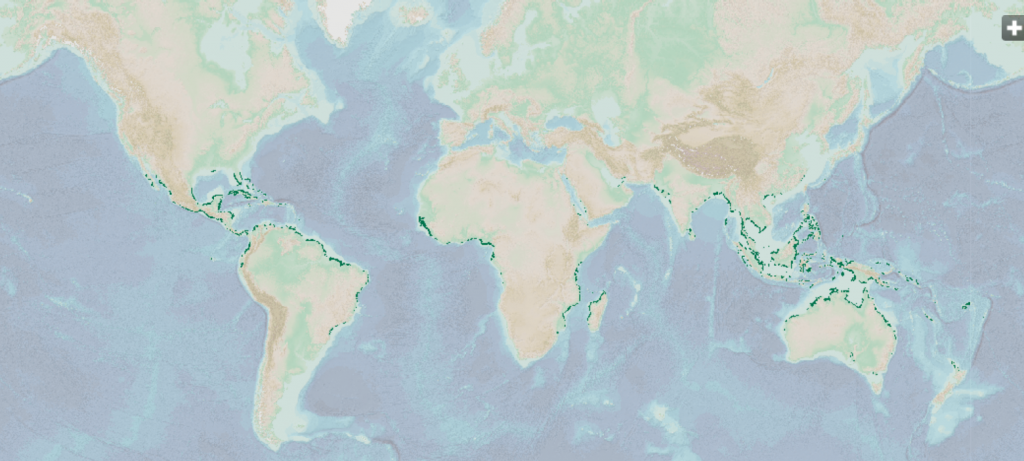

Magical forest, walking trees, mangals, snorkeling roots – this habitat can be called by many names. With a worldwide distribution in tropical to warm temperature latitudes, mangrove forests are not only incredible ecosystems, but a key player in climate resiliency and human livelihood. If you’ve been to the lower half of the United States, specifically southern Florida and the Gulf Coast of Texas, you may have come across this type of coastal wetland. If you’re more of a world traveler, it’s likely you may encounter a mangrove along your journey, as these wetlands reside on five out of seven continents on the globe.

Let’s get to know mangrove forests from root to tip. These coastal wetlands consist of groups of shrubs and trees that are uniquely adapted to estuarine tidal and marine conditions. Living in these ecosystems means that mangroves must be able to survive not only in waterlogged soils with oxygen-poor sediment, but also in saltwater experiencing daily tidal cycles. In order to grow in such harsh conditions, the roots are often sprawled above the water and below in sediment – a bit different than most plants. Along with the unique structure of their roots, mangroves can also filter out the salt from water as it enters their roots by secreting salt out of special glands on the leaves. This dynamic duo of adaptations allows the flowering part of the plant (the branches and leaves) to live above the water line, while the above and below ground root system maintains stability under the water.

When it comes to overcoming growth challenges, mangroves have really thought this one through. Regular coastal flooding can make most plants reproduction a more than difficult task. However, mangroves have adapted to use the tides and proximity to waves to their advantage through vivipary. This simply means that the offspring begin to grow while still attached to their parent plant, and in this case, far above the salt water. After pollination and germination, the seedlings fall into the water to then be swept away by the tides and wave action nearby. Next stop, the bottom of a muddy tidal wetland to grow out of the water and hopefully play a role in another mangrove colony.

According to The Nature Conservancy, there are approximately 70 species of trees and shrubs that make up mangrove plants communities of the world. Chilly or freezing waters are a big no no for mangroves, so it’s not a surprise that their distribution is only in tropical and subtropical latitudes near the equator. The various species across the globe are not necessarily closely related but do all share the distinct capability of growing dense roots out of the water in salty and often unstable conditions. For us here in continental United States, only three species of mangrove grow: black, red, and white mangroves.

Now, we’ve discussed the benefits and necessity for coastal wetlands on our blog before. But in standard fashion, each wetland habitat comes with its own intricate set of ecological and societal benefits. The fact that mangroves thrive in such harsh conditions is already remarkable; below are even more reasons to give them credit.

Habitat and Biodiversity

A mangroves maze of woody roots creates an intricate network of available habitat for numerous plants and animals. They are dense aquatic forests, a few miles in size, that provide areas for migratory birds, exotic fish and reptiles, heathy trees, and even furry friends like lemurs and panthers. As a nursery habitat, many small fish and invertebrates such as crabs and shrimp grow safely in mangroves and later move on to open water areas such as coral reefs. Recent data from The Nature Conservancy shows that mangroves are home to 341 internationally threatened species. And if you haven’t recognized their wonder yet, just Google a sloth swimming in a mangrove to really see the “wow factor”.

Blue Carbon Sequesters

Like all trees, especially in wetlands, mangroves absorb and store carbon from the atmosphere. What sets these habitats apart from the rest is how they store it. Once leaves and older trees die in a mangrove forest, they fall into the water and take the stored carbon with them to be buried in the soil. This is what we call “blue carbon” because it is stored underwater in the coastal ecosystem. Storing substantial amounts of carbon has proven to offset carbon emissions that drive the current climate crisis. The Smithsonian Ocean predicts one acre of mangrove forest can store about 1,450 pounds of carbon per year – roughly the same amount emitted by a car driving straight across the United States and back. Another reason to love mangroves and wetlands; they keep our air cleaner.

Coastline Protectors

This is a big one. Mangroves protect our shorelines and coastal areas more than we can imagine. As natural infrastructure, they provide protection to populated coastal areas by reducing flood impacts and property damages during extreme weather events. Mangrove forests buffer wave and wind energy as a first line of defense during strong storms. Also, their dense, aboveground roots slow down water flow and hold deposited sediment in place mitigating impacts from sea level rise. Last, their complex, underground root systems help cycle and filter excess nutrients reducing pollution and improving water quality.

Recreation and Culture

It’s a universal truth; the outdoors can bring people joy. Kayaking, snorkeling, fishing, birding, the list goes on. Mangroves can provide an invaluable natural experience because of their biodiversity and geographic location in some of the most tropical places on Earth. In addition to the everyday recreation, the traditional use of mangrove habitats dates to the BC times. These highly sustainable practices for hunting, timber, and food production are still in use today in some South American and African countries but may be lost with ecosystem degradation. The livelihoods of coastal cultures worldwide have become intertwined with mangrove forests whether it be through living spaces to nature clubs, small scale businesses to historic heritage sites.

Like many coastal ecosystems, these habitats unfortunately face a variety of threats and are being lost at a rapid rate. Whether experiencing habitat destruction from human impact like aquaculture or development, threats from sea level rise, damages from coastal storms and flooding – mangroves are up against some tough odds. The hard times of the modern age have brought on bigger and better ideas in conservation for mangroves, but all the answers are not clear yet. Science and education, reforestation projects, monitoring, policy adaptation – these are some of the ingredients to the recipe for success. But if there is a future for mangrove forests in our world, it may be useful to look at them as part of the solution. After all, they are masters at adaptation and overcoming intense challenges daily. From The Sundarbans of India and Bangladesh to the Galapagos Islands and The Everglades in southern Florida, mangroves are wetland wonderlands like no other.

Written on: September 22nd, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Natural Resources

By Beatrice Arce, MANO Project Fellow with the Hispanic Access Foundation

A year ago, I became an environmental professional after completing my educational journey in biology and environmental science. I am a first-generation college graduate, product of two tenacious Hispanic parents, my mother in administration at an environmental consulting firm and my father a salesman of fine oriental rugs in Houston, Texas. A mixture of an interest in my mother’s profession and love for science piqued my interest in this career; although, I did not know what I was getting myself into. Not in a bad way, though.

Stepping into the world of environmental consulting has become a transformative journey. For those who dedicate themselves to this profession, nature takes on a whole new meaning. After a year immersed in the field, my perspective on the natural world has shifted, affording me a new appreciation for its complexities and greater understanding towards its preservation. I am so very gracious to call my profession my own. Can you imagine being outdoors for work a quarter of the time?!

The Heck Are These Humans Doing to Nature?

First things first: what is an environmental consultant?! A majority of what my role consists of is measuring human interaction with the environment. Going into college, I was a bright-eyed student looking to positively contribute to conservation principles. But I’m not going to lie, I didn’t think it would be through the measure of human impact on the environment. Honestly, I had no idea what it would consist of. I just liked trees. When I enter a job site, I am more often than not identifying the altered and unnatural than nature itself. The projects I complete generally fall into three categories: prevention, reporting, and assessment. Our clients often request services mandated by state and/or federal regulations. However, I hope my work not only helps them meets these requirements but also sparks a deeper sense of environmental responsibility within their organization.

Consultants witness the consequences of industrial processes (e.g. oil spills), urban development (e.g. construction), and resource extraction (e.g. natural gas extraction). Yet, they also witness the potential for responsible, sustainable practices that harmonize with nature rather than exploit it (e.g. pollution prevention plans, Tier II reporting).

Let me list some projects I have gained experience from this position:

College gave me a great foundation to build knowledge on as an environmental consultant. But nothing prepares you for what you will learn in the field until you simply go through the motions. At the beginning of my consulting career, nature seemed untamed and overwhelming. I have now grown to recognize patterns within the noise and rhythms in specific industries.

What Growth Looks Like in Consulting

As a first gen, I definitely took a lot of guesses on how to land into a position like my own. Advancement was no longer linear as it once was. Although, I challenge you to see this chaos as a privilege rather than a setback! The non-linear configuration of a professional career allows specificity in particular interests you have. I have found myself to be forming into nonprofit leadership, which is a position I would have dreamt of five years ago! You’ll be surprised how quickly you adapt to situations and positions that were made for you. Kind of like nature.

It’s easy to become disheartened by the audacities you witness being done to the environment as a consultant. Although, with these gained experiences you also will begin to recognize nature’s remarkable ability to adapt and the environmental protections that are in place to mitigate damage. Ecosystems rebound from disturbances and state and federal agencies have regulations in place to safeguard natural resources. I have so much hope for the advancement in environmental stewardship!

Finding My Role

A wonderful past professor of mine by the name of Dr. Sam Atkinson asked me on the day I defended my M.S. degree, “So, what do you want to be when you grow up?”. And to that, I say, “The best I can be.”.

A beauty about science is constant learning. I hope one day to reach the level of a wise, intuitive consultant that uses their knowledge to inform local communities through grassroot initiatives (on top of my position, of course!). I believe environmental consultants hold a unique position to serve as an instrument of sustainable development and knowledge. I hope to meander to a specific passion in my journey. Find my niche in an ecosystem, if you will.

Written on: September 22nd, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Natural Resources

By Alondra Ureña, MANO Project Fellow with the Hispanic Access Foundation

The last few months have brought me a myriad of new experiences as an Endangered Species intern at the Sacramento Fish & Wildlife Office, from getting started on my internship deliverables to visiting my first wildlife refuge (I’ve now visited 4!), to celebrating Latino Conservation Week. I’ve participated in a 3-day training on Effect Pathway Manager (EPM), for the Service’s Information for Consultation and Planning (IPaC) system, helping to streamline technical assistance to agency partners. This is a large focus of my work during my internship, and I am in the process of assessing resource needs and collecting conservation measures for vernal pool fairy shrimp. I will input data into EPM to analyze the effects of human urbanization and development in the fairy shrimp’s habitats. It’s been a joy learning about vernal pools and fairy shrimp’s unique life cycle through a literature research extravaganza; it’s even more special knowing that I get to use my research to help protect these endangered Anostraca.

In between readings and research, I’ve participated in side quests that I could have only dreamed of as a young kid, and which have elevated my internship experience. I was lucky enough to attend Latino Conservation Week 2023 at the Minnesota Valley National Wildlife Refuge. I met other Hispanic Access Foundation interns and the MANO program associate, Yashira M. Valentin Feliciano. The night before the event, I went to my first baseball game in Minneapolis for the Twins vs. White Sox, the Twins won! Yashira and I met early the day of the event to set up our table with flyers, MANO swag including Latino Conservation Week 2023 stickers and tote bags, plus a temporary tattoo station. The temporary tattoo station was a hit: everyone, from children to moms to artists, were interested in representing the beautiful Latino Conservation Week 2023 emblem. We all enjoyed live music, performances from traditional Aztec dancers, and empanadas from a local food truck. The trip was an experience I’ll never forget, especially with how meaningful it was to celebrate ten years of the event with my Latinx community and my first time in the Midwest.

I’ve also expanded my fieldwork skills. I supported Dr. Jaymme Marty in setting pitfall traps and relocating over 60 endangered California tiger salamanders at Travis Air Force Base. I’ve participated in two field visits to Antioch Dunes National Wildlife Refuge for Lange’s metalmark butterfly surveys. We observed and identified other butterfly species including the California sisters, mournful duskywing, and skippers, but sadly not Lange’s metalmark butterfly. Out on the dunes, I felt an internal surge of peace as I realized I hadn’t spent as much time outdoors like this since I was a kid playing in the park with my primos and primas every weekend. When was the last time I enjoyed the outdoors, not thinking about watching a show after work or what I’d cook for dinner, but letting myself feel the sun and get lost staring at a butterfly? It’s been very healing for my inner child and after months of staying indoors for the pandemic and working in retail, the last few weeks have been a breath of fresh air. It’s been a sign of true alignment with my purpose in conservation as well as a reminder for me to never be afraid to be an intern, start over, and rediscover myself, my passions, and mi comunidad.