Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: July 26th, 2023 in Education and Outreach, Wetland Research

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Imagine yourself at one of these places in Delaware: up a rooted trail in the Piedmont region, down a sandy path near the coast of the Atlantic Ocean, or along a pondside trail in a mature upland forest. You snap a few photos and stop along the way to look at some wildlife, then you pop a squat next to some shiny leaves and tree with vines to chug your water with an afternoon snack. When you get home, you’re feeling refreshed, in the Zen zone with nature, and head to bed for night. The next day you awake to the feeling of an…oozy, itchy, rash? Rash?! Yep, there it is. The gleaming redness from coming into contact with poison ivy.

Many of us have been there, and a few of us have had the chance to meet some of the rarer plant species even worse than poison ivy. For this month’s blog post, we’re taking a look at the poisonous and dangerous plants that call Delaware home, many of which are found throughout the state’s wetlands. Though some are elusive others are easy to encounter, being able to identify these species can be an important step for smoothing sailing in the great outdoors.

Poison Ivy, Sumac, and Oak

Let’s start with the more notorious of the bunch, Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). This species grows plentiful pretty much anywhere – roadside, wetlands, public parks, forests, along the water’s edge, your backyard. In the early spring and fall the leaves of the plant are red or orange, and by the time summer rolls around they are a noticeable shiny green. The plant can grow as a woody vine up high or in a shrub-like fashion low on the ground, with each leaf consisting of three leaflets. All parts of poison ivy contain a dangerous skin irritant which most folks are sensitive to, and develop a reaction anywhere between 8 to 48 hours after touching it or encountering objects that have touched the plant.

Poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix) and poison oak (Toxicodendron pubescens) are more uncommon to the average person but are often seen in wetlands. Sumac is a close relative to ivy and oak yet tends to more allergenic and is distinctly taller than the other two species, reaching up to 20 feet tall. This plant can be identified by its large compound leaves with 7 to 13 leaflets, red stems, and clusters of waxy berries produced in late summer. Moving on to poison oak, this species leaves resemble an oak leaf (hence the name), but it is not a member of the oak family. This plant is also a low shrub that shares poison ivy’s three-leaf clusters, except its leaves are fuzzy and lobed with rounded tips. At most the plant grows about 3 feet tall and changes color seasonally; the leaves are green in the spring, yellowish-pink in the summer, and brown in the fall.

So, what is the common denominator between all three of these species? Urushiol. This light, colorless oil is released through all parts of the plant and when it comes into contact with human skin, an allergic reaction can begin. Reactions include itchiness, red rashes, swelling, and blisters, and the sensation for some can feel relentless. Urushiol is pretty toxic stuff and can remain hidden on tools, clothes, or really anything that has come in contact with the oil. If you have crossed paths with any three of these plant species, you’d most likely know it.

Stinging Nettle and Devil’s Walking Stick

Our next species is not only seen in Delaware’s wetlands, but also is considered a common garden weed. Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) is an invasive species that can be found in dense stands with stems that pack a nasty punch. This slender, upright growing plant can be anywhere from 6 to 8 feet tall and when in bloom, has greenish-white flowers in branching clusters. The stems of the plant have tiny needle-like stinging hairs that can cause a sensation for a few minutes up to several hours if touched – like a bad bee sting. To avoid the more painful way of identifying a stinging nettle, look for its drooping flowers, hairy stems, and oval, toothed leaves.

As an exotic looking native to the United States, devil’s walking stick (Aralia spinosa) says it all in the name. Growing anywhere from 10 to 25 feet tall, these plants clubbed-shaped branches have vicious prickles that really can getcha’. Not only can the plant be recognized by its sharp spines, but also by its enormous clusters of green leaves that form in a canopy at the top of the plant. The good news about this species is that you’d only encounter the prickles during the first year of growth; as the tree matures, the stems gradually lose their spines and form into more smooth branches. All and all, you don’t want to reach for this woody tree when you need a grab.

Poison Hemlock and Spotted Water Hemlock

Don’t let their being a member of the carrot family fool you – these last two plants are deadly. Poison hemlock (Conicum maculatum) is native to Europe, Africa and Asia, but invasive in North America. Ranging from 6 to 8 feet tall, this biennial plant (meaning it takes two year to complete a life cycle) is known to grow in meadows, wetlands, ditches, and at the edges of cultivated fields. An easy way to identify the plant is by taking a gander at its stems which are hairless with distinct purple blotches. It also emits an odor, like mouse urine some say, but getting that close to the plant to crush it for a sniff is not recommended. With glossy, dark, fern-like leaves and the physical characteristics, hopefully reading this blog will be your only encounter with identifying this species.

Spotted water hemlock (Cicuta maculata) is native to North America and is often considered the deadliest plant on the continent. The tough part about identifying this species is that the size and color of stems can vary greatly, ranging from solid purple or green, to green with purple stripes or spots. When folks have taken a closer look, it has been noted that the vein pattern, ending at the base of the notch of the leaf edge, is a more reliable form of physical identification. As an obligate wetland plant, it occurs naturally in freshwater swamps, floodplains and marshes, and along banks and roadside ditches. Again, it is considered one of the deadliest poisonous plants in the United States, so keep your distance.

Some key commonalities to remember between these two treacherous plants are that both hemlocks:

You absolutely want to steer clear of both poison hemlock and spotted water hemlock as all parts of the plant are poisonous to animals and humans alike. Some symptoms can be vomiting, stomach pain, diarrhea, seizures, muscle damage, increased heartrate, or potential death (just to name a few). Depending on the exposure – ingestion, inhalation, or direct contact – the severe symptoms can appear as soon as 15 minutes up to a couple hours. These plants are no joke; save the best for last, they say.

So, are you scared yet? This write-up is not meant to frighten you, but rather inform you. A simple takeaway to consider in the field is this: don’t touch a plant if you aren’t 100% sure what it is! All good scientists use their eyes first. An outdoor journey can take you many places in Delaware, so being able to identify dangerous plants can keep your adventures safe and your eye for the natural world sharp. Let alone give you a few less trips to the local Walgreens for Caladryl or Tecnu.

Want to discover more about wetland plants? Check out the DNREC Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program’s Delaware Wetland Plant Field Guide.

Written on: July 26th, 2023 in Natural Resources, Wetland Animals

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Summer means warm weather (ok hot), spending more time outside, exploring the woods, wading in streams, and fishing. This makes it more likely that you will encounter one of Delaware’s 14 species of turtles! Safe to say that there is a turtle in every type of habitat you visit.

From saltwater rivers and bays to freshwater creeks, forested wetland ponds, dry forests, wet meadows, and freshwater ponds- there are turtles in everyone! But can you tell which one you’re seeing?Can you Name that Turtle?

Let’s start out in the dry upland forest and work our way out to the Delaware River and Bay, learning a few fun facts about six popular turtle species that call Delaware home and how to identify them.

Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina)

The box turtle is a common and attractive species found in forested upland habitat. They are small but noticeable because of their gold and black patterned shell. No two are the same and their colors and patterns vary widely. Their red eyes are sharp and help them locate food such as snails, insects, flowers, mushrooms, and worms. I once interrupted a box turtle munching on a mushroom for breakfast.

Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina)

Snappers can be found in many different habitats: slow moving streams, rivers, ponds, impoundments, and brackish or salt marshes. What makes them distinctive? Their size and shape. They are the largest Delaware species when fully grown, topping out around 35lbs and 18 inches long! They have a pointy snout, long tail, and large webbed feet. You may see them crossing or along the road – they come out of water to seek sandy areas to lay their eggs generally in May. Watch out for these adaptable reptiles on the road but keep your distance- they are known to be a bit defensive (and flexible) and will bite if threatened.

Bog Turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii)

The bog turtle is one you are NOT likely to encounter but it’s special and I had to include it. This petite and secretive turtle is only found in the eastern United States, and they are considered critically endangered. Bog turtles are the smallest in North America, reaching only 4.5 inches in length. They are dark brown and black mottled with a distinctive gold to orange patch on the side of their neck behind their eyes. Bog turtles are difficult to spot not just because of their size, but also their habitat. They favor open, groundwater-fed wet meadows and bogs dominated by sedges and grasses. Decline in this species is largely due to habitat loss and fragmentation, and meadows succeeding into forests.

Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans)

Red-eared sliders are recognizable in many freshwater ponds and rivers, and as a favored pet. They are distinctive by a broad red strip behind each eye. Although popular and common to see in the wild, they are a non-native invasive species in Delaware. Oftentimes, pet owners release unwanted pets into the wild, which contributes to their spread and risks spreading disease to native turtle populations.

Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata)

Spotted turtles are another small, aquatic species freshwater habitats, growing to between 3.5 and 5.5 inches (small enough to hold in one hand). Their dark smooth shell is marked with bright yellow polka dots. They prefer shallow freshwater forested ponds and spend more of their time underwater among leaf litter. In the winter, spotted turtles bury themselves deep in muddy sediment and enter brumation, where they slow heir metabolism drastically so they can live without food and very little oxygen. Like other species who rely on specific wetland types, spotted turtle populations are threatened by loss and fragmentation of habitat. Collection for the pet trade also poses a threat to them.

Diamondback Terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin)

This is one of my favorite turtle species in Delaware. Terrapins are unique in several ways. First, they are the only saltwater turtle in Delaware (not counting the odd sea turtle). The female is larger than males, measuring up to nine inches versus about 5.5 inches in males. They are common in the Delaware Bay and Inland Bays and are often spotted poking their heads up along tidal creeks and bays. They have a beautiful black and white spotted skin with distinctively light ‘lips’. They are meat-eating, and particularly enjoy menhaden and silverside fish. Unfortunately, many terrapins die each year as mistaken catch in crab traps, where they drown unless turtle exclusion devices are used. Many are also struck and killed on Route 1 in the Inland Bays as they cross the road to seek sandy nesting habitat.

If you are lucky enough to encounter any turtle in the wild, be gentle and let them be. Observe them doing their turtle thing, take some pictures but resist the idea to take them home. Wildlife belongs in the wild!

If you see a turtle crossing the road and want to lend a hand, carefully pick them (NOT by their tail) and move them across in the direction they were facing when you found them. Do this only if traffic allows safe conditions for yourself.

For more details on these turtles and more visit this turtle identification guide!

Written on: July 26th, 2023 in Natural Resources, Wetland Restoration

By Brigham Whitman, Delaware Wild Lands

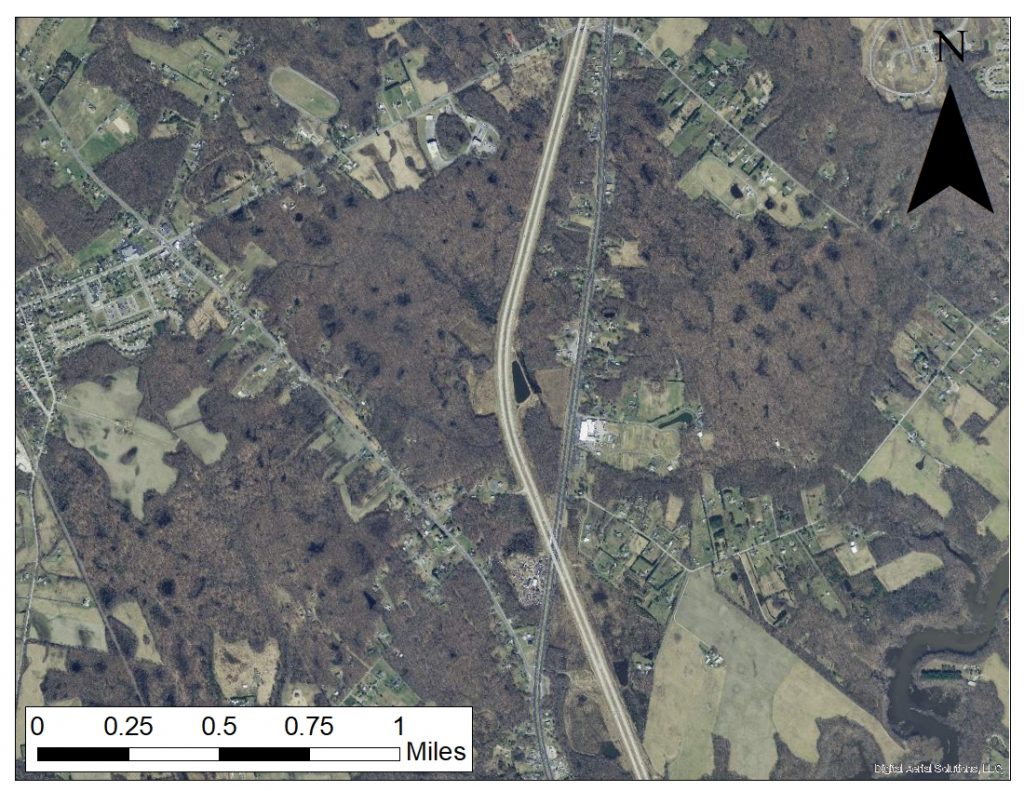

Taylors Bridge in southern New Castle County perfectly characterizes Delaware’s coastal flood plain: a mosaic of agricultural fields interspersed with patches of upland hardwood forest and the occasional residential development, surrounded by the waters of the Delaware Bay with fingers of marsh snaking throughout the adjacent low-lying areas. Aside from the natural beauty of the area, Taylors Bridge is also a highly biodiverse ecosystem, hosting 21% of the State’s flora in just 0.36% of the state’s land area. For these reasons, Delaware Wild Lands (DWL), the State’s oldest and largest land conservation organization, recently embarked on a major multi-phased effort to restore and connect natural habitats across DWL’s Taylors Bridge properties and protect the water quality of the Delaware River watershed. The first phase of this initiative, the now completed “NFWF Phase I” project, was funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) and at that point was the largest Federal grant DWL had ever received. Prior to this project, DWL typically focused on smaller grants because the organization was limited by its small staff size.

Last year, DWL and their partners, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Sarver Ecological, LLC, applied for and received a second, larger, and even more ambitious NFWF grant. In fact, this will now be the biggest Federal grant that DWL has ever received! This project, called NFWF Phase II, will rival the size and scale of DWL’s recent restoration projects at the Great Cypress Swamp in Sussex County. NFWF Phase II will add 75 acres of forest, seven acres of early successional habitat, and four acres of wetlands to the Taylors Bridge landscape. These restored areas will further connect and supplement the wildlife corridors that DWL installed in NFWF Phase I, thereby expanding the benefits of these corridors to new areas and additional wildlife populations. By utilizing a phased approach to restoration work, DWL can leverage the success of past grants to support current projects and produce results that might otherwise have seemed out of reach.

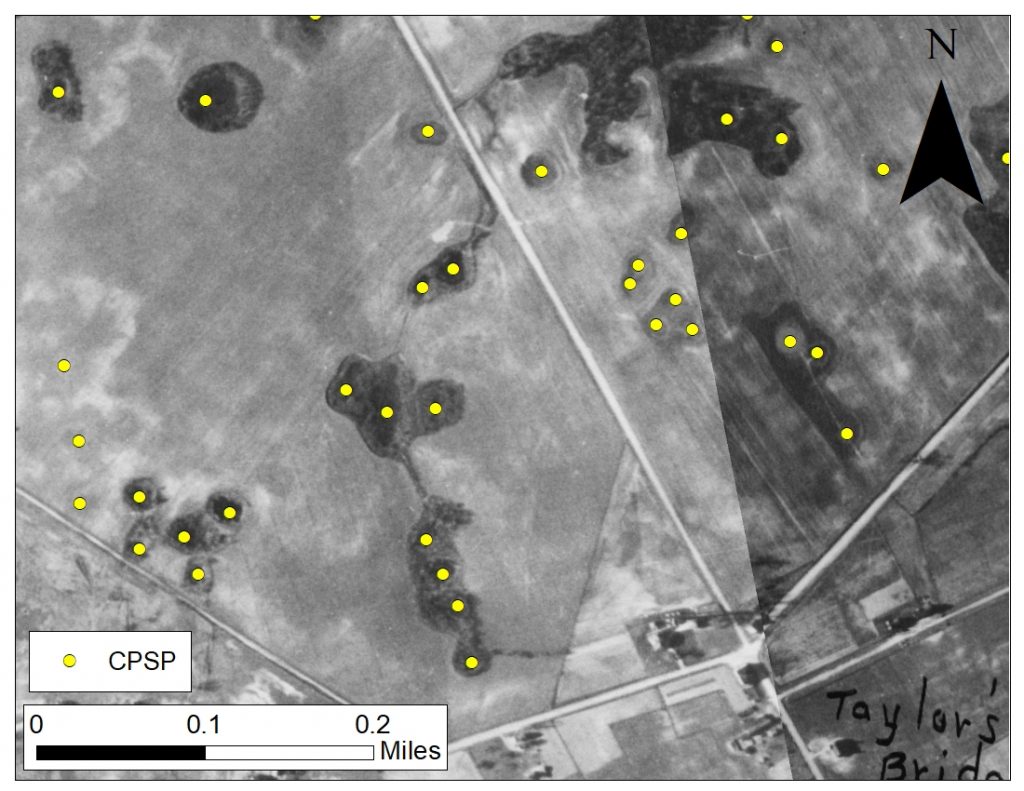

A major component of NFWF Phase II is the restoration of four acres of freshwater wetlands known as Coastal Plain Seasonal Ponds (CPSP), also called Delmarva Bays, Carolina Bays, or whale wallows. These ponds, which can be found across the eastern United States, are seasonal freshwater wetlands that are isolated from other water bodies. There are a number of theories about how these ponds formed, including meteor strikes, fish shoaling activity, or wind erosion during the Pleistocene Era. What is certain, though, is that without predatory fish, CPSP can provide unique habitat for rare and endangered species that can’t exist in other water bodies. CPSP were once a dominant feature on the landscape, and Taylors Bridge was a hotspot for these ponds. With the conversion of land for agricultural and residential use, however, many ponds were drained or filled-in. The CPSP that remain are now substantially threatened by development and sea level rise.

In preparation for the CPSP restoration, DWL staff referenced aerial imagery of DWL’s Dickinson Farm from the 1920s and performed subsurface soil investigations to determine where these ponds once existed. This year, staff will work with an excavator to restore the CPSP depressions to their original depth and place locally sourced tree stumps and logs to provide the structure necessary for a functional wetland ecosystem. DWL staff will then fill in the surrounding landscape with trees, grasses, and forbs.

Once NFWF Phases I and II are complete, the forested areas will serve as stop-over habitat for migratory songbirds and create a rare forest block in the region that will support forest interior dwelling wildlife species such as the wood thrush. The early successional habitat will benefit native bee and butterfly populations; provide habitat for snakes, turtles, red fox, opossum, skunk, and white-tailed deer; and support bird species such as the American woodcock, Baltimore oriole, indigo bunting, bobwhite quail, and turkey. The unique conditions in the CPSPs will benefit amphibians, reptiles, aquatic invertebrates, and rare insects and plants such as the state-endangered rare skipper, the amber-winged spreadwing, and the CPSP specialist plant American featherfoil. Farming activity will be streamlined as DWL makes a strategic effort to remove wet, marginal land from production in an effort to address sea level rise and manage the inland migration of marsh habitat on DWL properties. Furthermore, the trees and other vegetation that are planted will support conservation of the nearby marsh and protect the water quality of the Delaware River watershed. Landscape-scale conservation is a complex task, but DWL’s phased approach to conservation is achieving big results in Taylors Bridge.

To learn more about Delaware Wild Lands, visit dewildlands.org and follow them on Facebook and Instagram!