Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: May 17th, 2021 in Wetland Assessments

By Erin Dorset, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring amd Assessment Program

Here at the Wetland Monitoring & Assessment Program (WMAP), most fieldwork is done in the Delaware Bay and Inland Bays drainage basins, where waters move east to the Delaware Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. But, in 2018, WMAP had the opportunity to perform wetland assessments in a different part of Delaware, where waters drain west instead of east in the Chester-Choptank watershed. After a very buggy summer of field assessments and a couple years of data entry, analysis, and writing, WMAP is excited to share these new wetland condition results!

The Chester-Choptank Watershed

The Chester-Choptank watershed is in western Delaware and is part of the Chesapeake Bay drainage basin. The watershed continues out of Delaware west into Maryland. It is a headwater region, meaning that many streams begin here and eventually combine with other streams to funnel water west into the Chesapeake. The watershed is dominated by agriculture, wetlands, and upland forest.

WMAP visited and graded a random sample of 76 non-tidal wetland sites. All of these wetlands were one of three main types: flats, riverine wetlands, or depressions. Just as in other watersheds, WMAP used a rapid assessment method called DERAP (Delaware Rapid Assessment Procedure) to evaluate wetland health at all sites.

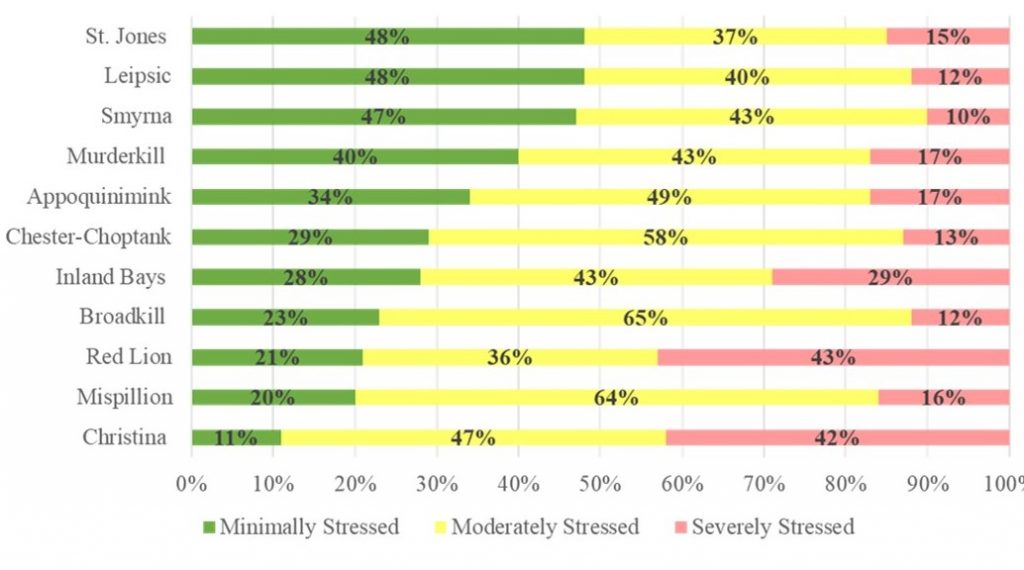

Based on that data, flat wetlands received a condition grade of B. Riverine wetlands received a B, and depressions got a B+. The overall Chester-Choptank watershed received a wetland condition letter grade of B, meaning that the watershed was doing moderately well in terms of wetland health. Compared with 10 other previously assessed watersheds, the Chester-Choptank fell right in the middle, with many of its wetlands being considered moderately stressed.

Buffer Blues

The most prevalent problems in the Chester-Choptank watershed weren’t necessarily found within wetlands but were instead often found surrounding wetlands. These problems are called buffer stressors. WMAP identified agriculture, development, roads, mowing, and channelized streams or ditches as buffer stressors that frequently occurred in the landscapes directly surrounding wetlands. Buffer stressors increase the risk of polluted runoff entering nearby wetlands, and they reduce habitat quality for wildlife.

Though buffer stressors were the most common, some other types of problems were found within the wetlands themselves. For example, invasive plant species were often present in riverine wetlands, which can crowd out native species and decrease habitat quality. Selective cut tree harvesting was a common habitat stressor in flat wetlands. Although selective cutting is not as damaging as clear-cutting trees, it can still negatively affect wetland habitat quality.

In addition, ditching was a common hydrology stressor in flats. Microtopographic alterations, such as skidder tracks from timbering vehicles and equipment, were also common hydrology stressors in flat and depression wetlands. Hydrology stressors like these can change the natural flow of water through a wetland such that plant communities, soil moisture, and groundwater levels may be negatively impacted.

Human Impacts Drive Acreage Trends

In addition to performing field assessments, WMAP used mapping data and software to explore wetland acreage trends in the Chester-Choptank watershed over time. It is estimated that the watershed lost about 39% of its historic wetland acreage by 2007 since early human settlement. Most of these losses were attributed to human development.

WMAP noticed that in recent years between 1992 and 2007, this pattern also held true, where most wetland losses were because of the construction of rural homes and housing developments. Agriculture was also a significant source of wetland loss. Most wetlands lost between 1992 and 2007 (71% of losses) were natural flats, and many natural depressions were also destroyed (23% of losses). These findings highlight the fact that most wetland losses in this watershed have been caused by direct human impacts.

Within that same 15-year time frame, some wetlands were also gained. However, most gained wetlands were ponds that were associated with human development or agriculture. Such ponds lack plants and do not resemble natural wetlands, meaning that their ability to perform beneficial wetland functions is limited. While it’s important to increase wetland acreage, it is also crucial that constructed and restored wetlands resemble natural wetlands as much as possible.

Working Together to Help Wetlands

Over half of the wetlands in the Chester-Choptank watershed were on privately-owned land. That means that private landowners can play a big role in improving the condition of wetlands in this watershed! Here are some simple ways that you can help:

Together, natural resource agencies and landowners can conserve wetland acreage and improve wetland condition in the Chester-Choptank watershed.

Want to know more about Delaware’s watersheds? Check out our web page that details the most current information about the health of wetlands on a watershed level!

You can also view and download all of our data on non-tidal wetlands, including the Chester-Choptank watershed, here.