Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: March 6th, 2020 in Wetland Assessments

By Catherine Medlock, Graduate Student of University of Delaware

In tidal marshes, accurate representation of marsh elevation or height is critical for understanding sea-level rise, tidal inundation, and storm surge. Small changes in marsh elevation can significantly change the water movement (hydrology), plants (vegetation), and habitat. Our study aims to look at and correct a remote sensing method known as light detection and ranging (LiDAR), in order to provide accurate elevation data to scientists and coastal managers in Delaware.

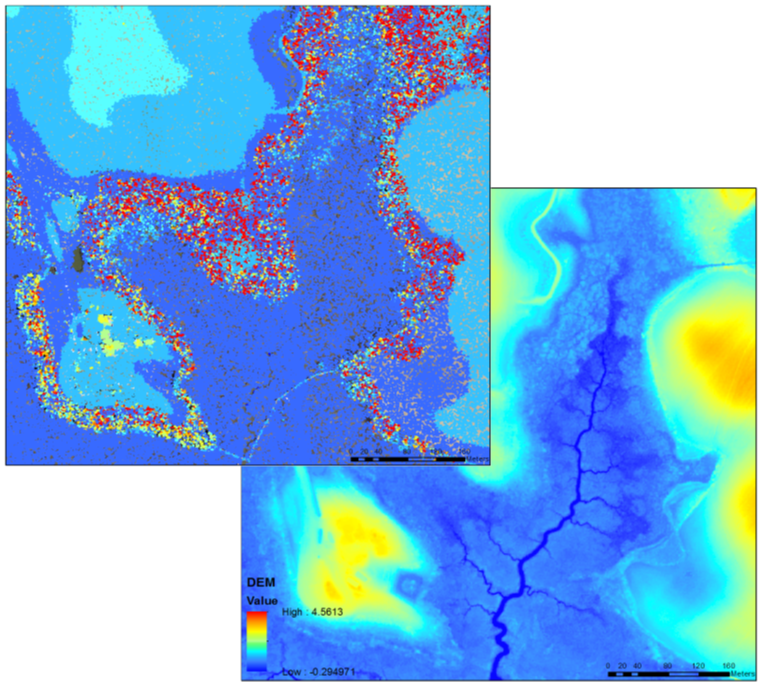

LiDAR may sound complicated, but it is really quite simple. LiDAR uses light pulses emitted from a sensor to gather 3-dimensional information about the earth’s surface. The LiDAR data is delivered as a 3-D cloud of individual points representing the ground, trees, buildings, and power lines. Ground elevation points are extracted from the point cloud, which are then used to create a digital map of the surface elevation called a digital elevation model (DEM). LiDAR is used in many coastal applications due to its high accuracy and density of data over large areas. For reference, in one square mile, LiDAR can collect over 7 million points!

LiDAR was collected across the entire state of Delaware in early 2014. LiDAR is an incredibly useful tool for topographic mapping, flood risk management, shoreline mapping, precision agriculture, and forest planning and management. Unfortunately, in tidal marshes, the light pulses are unable to penetrate through the dense vegetation to reach the marsh surface. This results in an average overestimation of 9 to 25 cm in elevation between the DEM and the actual marsh surface, depending on the marsh vegetation. This error can in turn lead to underestimations in the extent of coastal flooding and potential marsh erosion.

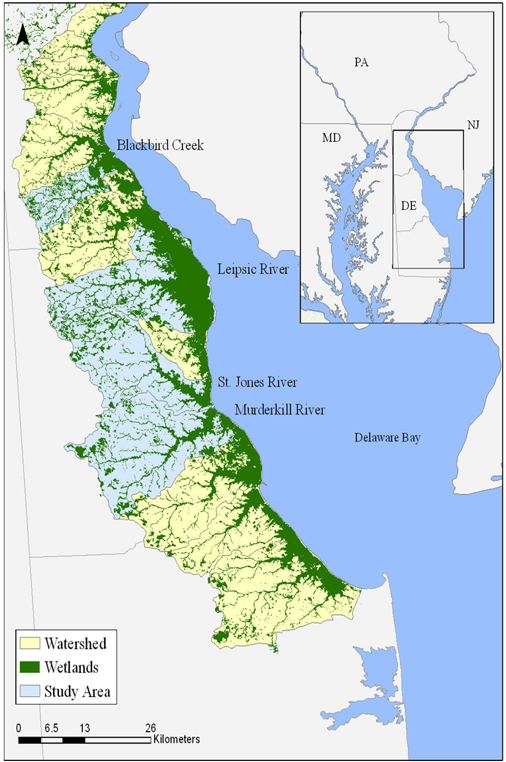

The goal of our study is to reduce the vertical error of LiDAR for mosquito ditches and the marsh platform, and provide a DEM correction that can be applied to all tidal marshes in Delaware. Four watersheds were identified to test several LiDAR correction methods: Blackbird Creek, Murderkill River, Leipsic River, and the St. Jones River. Over several years, we collected over 1000 GPS measurements with centimeter (cm)-level accuracy across the four marshes to compare DEM elevations with actual marsh elevations, and aid in the DEM corrections. As a result of the study, we plan to produce corrected DEMs, in order to model tidal inundation and assess marsh vulnerability in Delaware’s coastal marshes.

Historic human activities in marshes further complicate DEM corrections. In the 1930’s, the civilian conservation corps (CCC) dug mosquito ditches across marshes in Delaware to reduce mosquito populations by draining shallow pools on the marsh surface where mosquitoes reproduce. Enhancing drainage of the marsh surface actually transformed historically low salt marsh into high salt marsh habitat. Mosquito ditches are extensive throughout Delaware, and still visible in imagery today!

Mosquito ditches have a different elevation and vegetation than the rest of the marsh, so they require their own separate DEM correction. In efforts to correct the DEM for both the marsh platform and mosquito ditches, we hope to gain a better understanding of marsh inundation and vulnerability, and provide a useful tool to aide coastal scientists and managers in preparing for future environmental changes in Delaware’s marshes.