Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: May 18th, 2020 in Wetland Animals

By Elisa Elizondo, University of Delaware

Colloquially known as marsh hens, the Clapper Rail (Rallus crepitans) is a vocal inhabitant of saltmarshes across the eastern coast of the United States and down into the Caribbean. Many of the first in-depth observations of Clapper Rail occurred in the mid-Atlantic, and in Delaware, Brooke Meanley documented much of their ecology. The northern Clapper Rail populations, including Delaware, have been declining based on extensive survey work conducted by the Saltmarsh Habitat Avian Research Program (SHARP).

Rails are typically secretive in nature, making their populations very difficult to monitor. One important measure of population health is nest survival, as the rate at which nests survive determines the number of offspring that can be produced to join the population in the following year.

Beginning in 2018, research conducted through the University of Delaware has been monitoring Clapper Rail nests in Delaware. Locating the nests can be tricky and is accomplished by searching on foot and using thermal imaging taken from a drone. Once a nest is located, the eggs can be floated in a container with freshwater to help determine their age. As the eggs develop, gas builds up within the egg ultimately causing it to float. When the eggs are close to hatching, they will float right to the top!

Often in the early stages of the nest, the adult rails are not spotted. When the eggs initiate hatching, however, the adults are at their most defensive. Both the male and female Clapper Rail incubate the nest and tend to the chicks. They employ various techniques to protect their nests including loud vocalizations, using their wings to appear larger, or feigning injury in the hopes of drawing off the predator. The chicks are ready to run into the marsh 1-2 hours after hatching, but currently there is no information on how many of those chicks make it to adulthood.

In order to learn more about adult Clapper Rail survival and habitat use, the University of Delaware research crew is deploying GPS tags. These tags can be programmed to take GPS points throughout the day. Those data are then either sent to a satellite then downloaded online or downloaded manually by getting close enough to a bird to transmit the data to a handheld device (the download method varies by tag model).

Each tag can provide hundreds of locations that we can use to determine their territories. This helps us to determine what areas each individual bird is using and the overall types of habitat the birds seem to prefer. The satellite tags can continue to transmit for several years to help identify where the birds migrate to as well.

These data can sometimes yield surprising new information; in 2019 we discovered a tagged male bird with two nests ~5 m (approximately 16 feet) apart within his home range! Blood samples were drawn from both the adult and several chicks from the nests so that paternity can be evaluated in the lab.

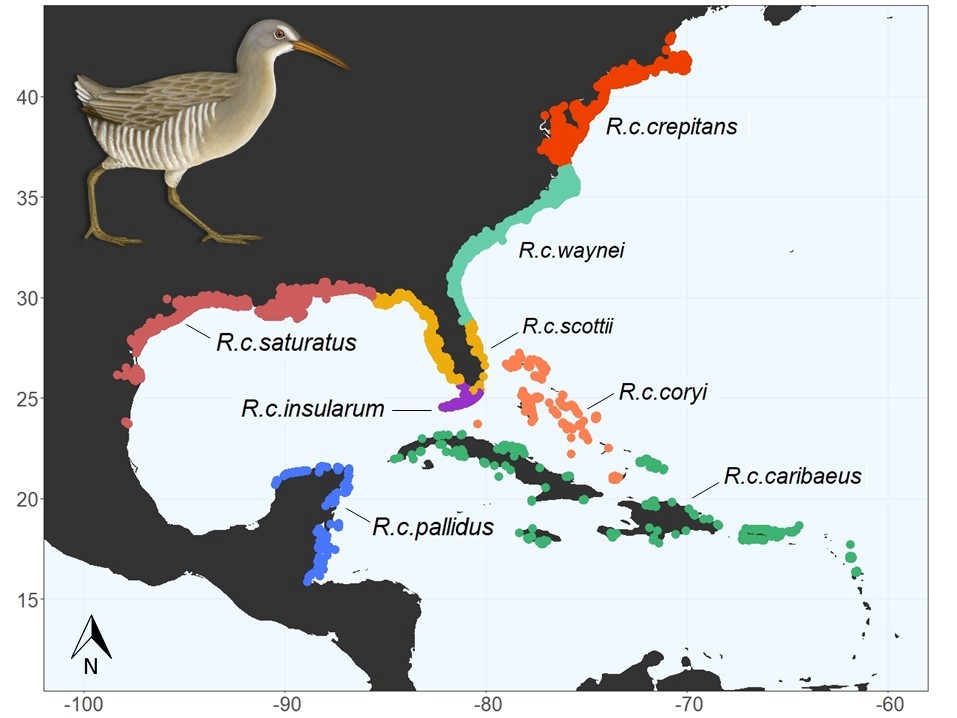

There are 8 subspecies of Clapper Rail, and only the Northern Clapper Rail (R. c. crepitans) migrates. Here in Delaware, hunting band records from the 1950s and recent satellite data from birds tagged in Delaware indicate that Clapper Rail from Delaware winter in South Carolina and surrounding states. Understanding the population connectivity, or the degree to which populations interbreed, is important in determining population trends and areas of high conservation concern.

To determine the relationship of Clapper Rail in Delaware to other regions, blood samples are currently being collected from all tagged birds. Through collaborations with other state agencies and academic partners, additional samples will be collected from across the U.S. range of these subspecies to assess population connectivity using Next Generation Sequencing techniques. Given that Northern Clapper Rail populations seem to be in decline, it is increasingly important for us to understand how their populations relate to non-migratory subspecies.

This research is made possible by many funding resources, including the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control, the Delaware Ornithological Society, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, and the University of Delaware.