Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: March 14th, 2016 in Education and Outreach

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Winter storms and nor-easters brought excess rainfall, rough seas, and unseasonably high tides to Delaware this winter, highlighting the value of nature’s first line of defense against coastal storms; wetlands. Up and down Delaware’s coast, roadways were made impassable due to rising seas, buildings were battered by winds and water, and dunes and boardwalks were washed away by angry waves.

But don’t’ fret, there is hope in minimizing the effects of storms on your property: Protect, Preserve and Restore Wetlands! Wetlands have the innate ability to store flood waters, buffer storm surges, and prevent erosion. Did you know that peak floods can be reduced up to 60% in watersheds that contain 15% wetlands(NOAA Digital Coast)?

There are multiple things you can do to protect and preserve wetlands:

Written on: March 8th, 2016 in Wetland Assessments

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Every summer since 1999 our Program has gone out into the wilderness to assess non-tidal wetland health in Delaware’s different watersheds. Why you ask? Well, we want to see how healthy Delaware’s wetlands are and if they are able to perform the natural tasks that make them so valuable. We identify which wetlands are in good shape, areas where wetlands are not doing so well and why, and highlight ones that could use a little tender love and care (AKA, they are good candidates for restoration and protection).

In 2015, we focused on the Appoquinimink Watershed located in the northern third of Delaware. A watershed is an area of land in which all water drains and runs off towards a specific body of water, in this case the Appoquinimink River, and has a natural boundary defined by the tops of hills or ridges.

To begin our expedition, we divided the wetlands up by type depending on how they receive their water (groundwater, surface water flow, and precipitation) and where they exist (along a stream, in a shallow depression, and on forested terrace). Then we randomly selected wetland points on a map to be evaluated. We ended up visiting 31 headwater flats, 35 riverine and 29 depression wetlands throughout the summer in the Appoquinimink Watershed. As we hiked through each of the 95 sites, our team looked for a variety of features that could cause a wetland to be stressed or impacted. These features, or stressors, are broken up into three categories: habitat, hydrology and buffer.

Habitat stressors involve the physical and biological characteristics of the wetland and can include presence of invasive plants, excess nutrients, forest harvesting, farming or roadways.

Next up are the hydrologic stressors. Hydrology deals with water; what it is doing and where it is located (or not located) in the wetland. Some of the questions we ask ourselves are: Have ditches been added to the wetland? Has the stream channel been straightened or deepened? Does it have a stormwater pipes or point source pollution entering? Has it been filled or dug out?

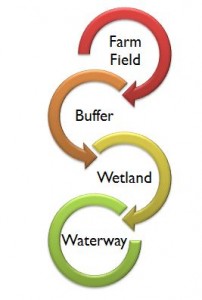

Last on the list to take a look at are the buffer stressors. A buffer is a zone of land just outside of the wetland that has the ability to protect a wetland from disturbances occurring in the surrounding upland landscape. If severe impacts are too close to a wetland, it may overwhelm it causing it to not function properly. If a wetland has a good buffer, then it has a first line of defense against excess nutrients, pesticides or soil runoff, and that wetland can further protect pollution from entering waterways (Figure 1.). Some of the buffer stressors that we look for include farming practices, developments, roads, landfills, golf courses and ditches.

Why don’t you give identifying wetland stressors a try. Can you identify the major stressor that was put in the below wetland?

If you guessed roadway, then you were right! As we go through each of these stressor categories at a site, we mark down what we see (like the roadway in the above picture), and tally everything up to give that wetland a score. The more stressors at a site, the lower the score, the poorer the health of that wetland. We are currently in the process of compiling all 95 scores for the a Wetland Health Report on the Appoquinimink Watershed.

The information gathered in this report will be used to compare wetland health across Delaware’s watersheds and make recommendations to landowners and policy makers to improve the health of Delaware’s wetlands. Be on the lookout for the Appoquinimink report in 2018.

Want more information on this process? Check these resources out:

Delaware Rapid Assessment Procedure

Watershed Wetland Health Reports