Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: December 22nd, 2025 in Education and Outreach, Natural Resources

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Sanctuary. All seek it, some search, and a lucky few can find it. As we know, these “sacred” spaces can come in many different forms and represent an untouched meaningfulness which is irreplaceable. One of a kind so to speak. At the far end of the Alaska Peninsula, where the land turns into the Bering Sea, sits a haven of this nature. A remote wetland habitat few know exist and even fewer visit, the Izembek National Wildlife Refuge. The wetlands across this landscape are some of the most unparalleled habitats in world, providing sanctuary to plants and animals of critical importance and are an intact wilderness of global significance. Get to know this refuge and explore its ecological value to all.

The Basics

Due to its remote location and geographical position, the majority of us will never visit this refuge, so we need to know what we’re working with. Though it is the smallest wildlife refuge in Alaska at 310,000 acres in size, roughly the same acreage as Grand Teton National Park, it’s one of the most ecologically unique refuges in the entire U.S. system. Established in 1960 by President Eisenhower as the Izembek National Wildlife Range, the country knew then this was a special place. In 1980, President Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) into law which redefined the area as the Izembek National Wildlife Refuge. ANILCA designated 300,000 acres (nearly all Izembek) as a Wilderness Area, which in congressional language means these areas are designated and intended to have the highest levels of protection to lands by permanently restricting roads and other industrial developments – on top of a smattering of other protections and regulations. Moreover, it was the first place in the U.S. to be designated under the RAMSAR Convention as a Wetland of International Importance with focus on its series of lagoons and surrounding marshes along the coasts. This place is a big deal.

The allure of this refuge has to do with its reclusiveness. Weather wise, you can typically expect cold temperatures with rain, wind, and fog with virtually no visitors. If you happen to have gotten there, it’s probably through the local community of Cold Bay (outside of the refuge itself) via boat, small plane, or off-road vehicle. Though Izembek has a headquarters with a mini visitor’s center in Cold Bay, there are no public-use facilities in the refuge. Just beautiful, sprawling wilderness.

The Wetlands, Water, and Wildlife

Tucked between the rich waters of the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea, the refuge is full of complex coastal wetland habitats that span miles. Its brackish waters also encompass hundreds of lakes, meandering streams, glaciers, and hot springs. The low bush tundra surrounding the wetland landscapes goes from sea level to volcanic mountains above 9,000 feet. Yes, you heard that right, wetlands and volcanoes right next to each other in a tundra climate. One of the most notable features is the Shishaldin Volcano, that despite having intense eruptions, has held its almost perfect cone shape for centuries.

At the heartbeat of these wetlands is the Izembek Lagoon, home to the world’s largest beds of eelgrass (Zostera marina). Spanning approximately 42,000 acres (65 square miles), these shallow beds are an essential source of food for many species throughout the refuge and a critical plant in coastal wetlands. The eelgrass meadows provide habitat and create nurseries for invertebrates, fish, and birds and create a corridor for larger mammals who roam Izemebek – but we will get to those in a bit! To top it all off, eelgrass is known as the “rainforest of the sea” and acts as a good ecological indicator of an ecosystem’s health because of its connection to species diversity, water quality, carbon storage, and shoreline protection.

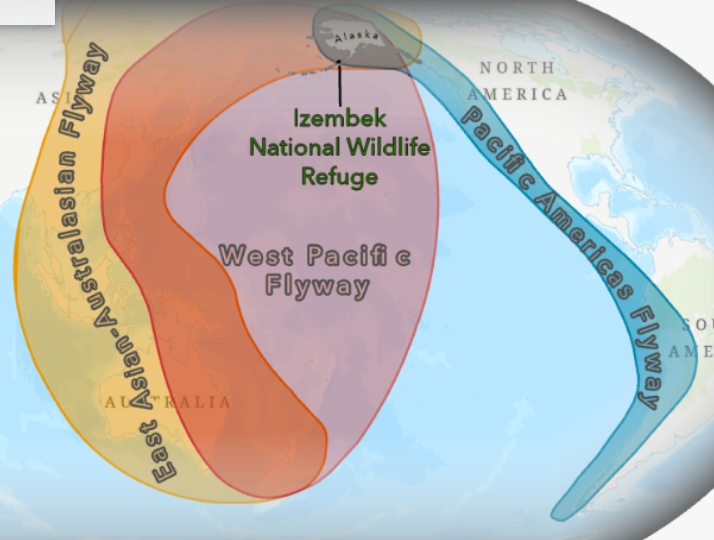

Now onto the wildlife. In true wetland form, seasonal and permanent havens exist for more than 200 bird and mammal species and 40 fish species across Izembek. Three major migratory bird flyways collide making the refuge a hotspot for our incredible avian friends: the East Asian-Australasian, West Pacific, and Pacific Americas flyways. Millions upon millions of birds visit the shores of the lagoons and wade into the wetlands for food, to find shelter, and take a load off after a long journey. Virtually the world’s entire population of the Pacific black brant and emperor goose stop at Izemebek to feed on the massive eelgrass beds during their seasonal migrations. Some species fly over 2,500 miles to reach the refuge! As a crucial wildlife travel corridor along the Alaska Peninsula, Izembek’s isthmus provides a passage for brown bears, caribou, and wolves, as well as safe places for them to rear their young. Year-round residents like the tundra swan, red fox, and moose can be seen frolicking on the shorelines. Minke, gray, and killer whales migrate by the thousands along the cold-water coasts. Hundreds of thousands of salmon begin and end their life cycles in Izembek’s streams. Such a plethora of species are supported in this dynamic coastal ecosystem, and the list could go on, but below are a few more.

Alaska truly is the last frontier. Its abundant, untouched landscapes and habitats take us to a place where wildlife and wilderness rule, and the outside world has no presence. This refuge where worlds collide – wetlands, volcanoes, underwater meadows – few and far between places like this exist in our world. The wildlife, the Alaskan culture, the plant species, all of it deserves to be protected, and more importantly, studied and shared. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says, “The scenery, wildlife, and wilderness experiences that the refuge offers are truly unique – the experience of a lifetime.”. If the folks who run the show say Izembek is amazing, it must be a natural spectacle, even by Alaska’s standards.

Written on: December 22nd, 2025 in Wetland Animals

By Alison Stouffer, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

If you are like me, you have likely been driving down a rural road, paddling through a tidal wetland, or going for a stroll through a state park and seen a furry, brown animal that had you doing a double take. That wasn’t a weird looking dog all by its lonesome, was it? There are a handful of mammalian species that this animal could be, but they often look similar, if not identical. Read on to see if you can correctly identify these fury, brown mammals in a fun game of This or That? Answers can be found at the end of this blog post.

Round 1: Beaver or Groundhog?

For Round 1, you must decide which image belongs to the North American Beaver (Castor canadensis) and which belongs to the Groundhog (Marmota monax).

The North American beaver is the largest rodent in the United States and is considered a keystone species and ecosystem engineer due to its dam-building pastime, which significantly impacts the structure and function of the surrounding environment. For example, beaver dams – created from trees, sticks, and mud – create important wetland and floodplain habitats adjacent to open water, filtering out sediment and pollutants from the water column. These animals also rely on these wetland habitats as a source of plant-based nutrition for their herbivore diet. The North American beaver is easily identifiable by its long, flat, black tail and large front teeth. In addition to its tail, the beaver’s webbed feet, waterproof fur, and ability to hold its breathe for long periods of time make this animal suited to life in and around water.

The groundhog – also known as a whistle pig or woodchuck – is the most geographically spread marmot species in North America. Unlike the beaver, groundhogs are not typically found in wetland habitats. Instead, they prefer well-draining soil within forests and fields where they can build their dens and stay dry. Dens consist of a network of underground tunnels, which can provide habitat for other animals when abandoned. The groundhog is easily identifiable by its favorite posture – standing on its hind legs – and its short, bushy tail. These animals are also adapted to life underground, having strong claws for digging and short ears that flatten over the ear canal to prevent dirt from entering it while burrowing.

Round 2: Mink or Otter?

For Round 2, you must decide which image belongs to the American Mink (Neovison vison) and which belongs to the North American River Otter (Lontra canadensis).

The American mink has a geographic range that spans the entire continental United States, except for Arizona (I wonder what AZ did to deserve a mink exodus…) and are typically found in forested wetlands near streams, rivers, ponds, and lakes. These animals are well-adapted to their semi-aquatic habitats, using their waterproof fur and partially webbed paws to propel them through and under water to hunt for prey. The American mink – a carnivore – will eat small land mammals like mice and shrews, as well as fish, ducks, and frogs. When not in the water, they can be found hunkered down in their bankside burrows. As a wetland-reliant species, these animals are threatened by habitat loss and can be used as an indicator of wetland health.

The North American river otter inhabits most of the continental United States, except for more arid, desert states such as New Mexico, parts of southern California, and Texas. Like the American mink, North American river otters are found near aquatic habitats such as rivers and lakes; however, can tolerate both freshwater and saltwater and thus can be seen floating along the coastline or within saltmarshes . These animals are equipped to llive in the water, having nostrils that close and allow them to hold their breath for up to 8 minutes, webbed paws for swimming, dense fur for insulation, and whiskers that help them hunt in the water when other senses are reduced. The river otter is dependent on the waters adjacent to wetland habitats, relying on them for much of their diet (i.e., fish, amphibians, turtles, aquatic invertebrates, etc.).

Round 3: Muskrat or Nutria?

The common muskrat is native to North America and found throughout most of the continental United States but has been introduced – and become invasive – throughout parts of Eurasia. These large rodents are highly dependent on wetlands for survival; however, they can tolerate both fresh and salt water. Wetland habitats, such as ponds, lakes, marshes, and swamps, provide protection from the elements and food resources. Muskrats burrow underground within the banks of wetlands to create their homes, coming and going through underwater entrances. They also rely on their habitat for food, primarily consuming aquatic vegetation such as cattails. As a semi-aquatic animal, the muskrat is suited to the water as they have vertically flattened, scaled tails to help propel and steer them through the water, dense fur for insulation and buoyancy, slightly webbed back paws, and an ability to stay underwater for 12-17 minutes at a time.

Nutria are a rodent native to South America that were introduced to Eurasia and North America through the fur trade. In some part of the United States, nutria are considered an invasive species due to the damage that can be caused to irrigation infrastructure (i.e., dikes) from burrowing and competition for resources with native species, such as muskrat. Like muskrat, nutria are a wetland-dependent species that live primarily in freshwater marshes, lakes, and streams. They rely on wetland habitat for food, eating the roots, stems, and leaves of aquatic vegetation. These animals will also groom and feed off of DIY vegetation platforms and floating logs. Nutria, like muskrat, have dense fur for insulation, webbed back paws, and an ability to stay underwater for more than 10 minutes. However, their long tails are lightly covered in hair, rather than scales.

Hope you enjoyed the guessing game! The answers are below.

Round 1 – A) beaver, B) groundhog

Round 2 – A) otter, B) mink

Round 3 – A) nutria, B) muskrat