Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: March 11th, 2019 in Wetland Restoration

By Jules Bruck, University of Delaware

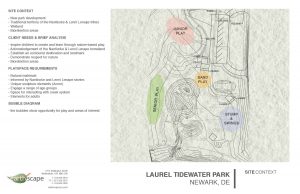

Great things come naturally in Laurel, Delaware including the new green infrastructure treatments that are popping up along the Broad Creek – home to the future Laurel Ramble. This past summer the Sussex County Conservation District broke ground on a parcel of land in the center of the Ramble plan called Tidewater Park. The project, designed to improve water quality in the area, was engineered by ForeSite Associates of New Castle, Delaware. Work began on two treatments – a vegetated bioswale and a constructed wetland, in early summer 2018.

The Bioswale

The bioswale was selected as a priority treatment due to the following factors:

The 300’ long gently meandering bioswale forms a diversion for runoff, permitting easier installation of the constructed wetland and fish habitat. It creates a viable, ecologically appropriate solution to aid in reducing pollutant loads to Broad Creek, which in turn makes a significant step forward toward meeting the demands of the town’s Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) permit.

The bioswale represents a permanent change in drainage patterns on site, and it is expected to be a long-lived treatment as long as the inlet is regularly inspected and maintained. It’s designed to meet the total maximum daily load (TMDL) requirements for 2.23 acres of existing impervious surface in the drainage area.

The Constructed Wetland and Tidal Fish Cell

The constructed wetland is approximately one acre is size, and planted with native grasses and sedges as well as some flowering herbaceous plants. It was designed to accept some stormwater surface flow from the upland areas as well as to allow the waters of the Broad Creek to enter during high tides.

According to the Stormwater Management Report prepared by FA in July 2016, “In keeping with the theme of the proposed playground as a nature-based feature and the Town’s goal to promote Laurel’s ecotourism industry, a tidal fish cell has been designed adjacent to the constructed wetland.”

“This tidal cell does not serve a regulatory function other than convey discharges from the constructed wetland to Broad Creek. Overflow from the constructed wetland is designed to discharge through a narrow v-shaped notch in the weir wall to help detain and slowly release runoff to the tidal fish area.”

Creating Native Wildlife Habitat with Native Plants

The new landscape has diverse plantings that will increase the native biodiversity on site and attract wildlife such as ducks and butterflies. We look forward to the spring so we can evaluate how the plants survived over the winter.

We anticipate the wetland will become important habitat for spawning fish, such as American Shad. In fact, we had to be careful about working in the water during the summer to avoid disruptions during critical times for the local native fish.

Good Planning = Easy Maintenance

After some minor touch ups and replanting of the plants that did not make it through the winter, the treatment should be relatively easy to maintain. University of Delaware landscape architecture students worked on a landscape management plan under the direction of Dr. Jules Bruck thanks to funding from UD Community Engagement Scholars and DE Sea Grant. We continue to work with the Town of Laurel to develop a management plan. We also want to keep an eye out for any invasive plants and provide training for the town’s landscape crews to help them identify and control non-native plants and noxious weeds. To that end, we’ve asked Tracy Wootten of Cooperative Extension to lend us a hand! We are working on some ideas to engage facilities and the community so the project remains a benefit to all. The Tidewater Park plan is a different type of landscape and you’ll start to see more of it as the Ramble plan is installed. It’s not just ornamental, it’s a working landscape.

This project was funded through two grants – the DNREC Community Water Quality Improvement Grant and the DNREC Chesapeake Bay Implementation Grant Program. Interested in learning more about this wetland and bioswale creation or the Laurel Ramble? Visit the Reimagining Laurel website. http://www.reimaginelaurel.net/