Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: September 26th, 2022 in Education and Outreach

By Olivia Allread, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

For many of us about to read this blog post, we may not be artists at heart. In fact, some of us may have not picked up a paint brush or sculpting clay since middle school. Everyone has their niche, right? Luckily a benefit of modern times is being able to participate in cross sections of expression. Our appreciation of the natural world, much like the work of an artist, can be influenced by the mediums we interact with. Some artists prefer photography to charcoal drawing, just like some scientists prefer outdoors field work to structured lab procedures. Let’s go past the policy making and not worry about grant deadlines to take a look at the world of wetlands through a different lens: art making.

Nature and art both have an extremely long history of cultural attachment to our societies and livelihoods. Art itself is not only there to just make things pretty, but to make varying kinds of discoveries about subject matter. A great example are the prehistoric cave paintings at the early stages of human civilization. These pieces of art dating back anywhere from 40,000 to 70,000 years ago provide context to communication, as well as human’s relationship with animals and the environment of that time period. Both art and science were needed to fully understand nature and its effects on people.

If you have read some of WMAP’s previous blog posts, you’ll see that threats to wetlands include unsustainable urban development, agriculture, pollution, and invasive species, to name a few. But the biggest threat is one of perception. Promoting the understanding of these critical habitats requires a form “je ne sais quoi”, utilizing multiple forms of interpretation and communications skills. As we all know, changing people’s minds is no easy task. New perspectives or meaning can be found through an acrylic painting of a marsh in a museum or Excel-based table in a wetland report. The end goal can often be the same: moving society towards ecological understanding and even sustainability.

Here is a deeper look at artists of all kinds that are using their creative skills in support of preserving, restoring, and interpreting wetlands.

Heading south (far south) our first stop is in Costa Rica with landscape artist Tomas Sanchez. Originally from Cuba, this painter specializes in hyperreal art using a mix of memory and experiences to cultivate wetland images. Sanchez has been in the game for quite a long time having been around during the 1980’s when Cuban art was heavily censored. Since then, he has been painting to create remarkable images of wetland paradise to comment on humans interactions with nature and broader environmental issues. Not to mention, his recent set of works in 2022 are sustainably produced by Hahnemüle, a soon to be carbon neutral paper mill that uses reusable fresh spring water.

A true mix of public art and eco-conscious infrastructure is showcased with the art from Lillian Ball. As an art activist, Ball has an extensive background in providing commentary on environmental issues through solution-based approaches. Since 2007, her WATERWASH projects throughout New York state have incorporated artistic designs into stormwater remediation, wetland restoration, and outreach opportunities. From native plants to a water access park to green infrastructure for runoff pollution, her work can be applicable to wetland issues happening in communities worldwide.

Birds and landscapes are what bring our next artist pure bliss. Hailing from Ontario, Canada, Ron Plaizier has specialized in works of the 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional species while also incorporating landscapes throughout North America. Using acrylic paint on canvas or mason board, he captures the balance between human development and wildlife to showcase the results of conservation; up-close and personal images of wetlands species that reside in these ecosystems. Decorated for his efforts several times over the last few years, Plaizier is a signature member of Artists For Conservation and has even been featured Ducks Unlimited Canada’s National Art Portfolio donating artwork to help raise funds for wetland conservation.

Across the pond in the UK, an illustrator and paper artist Jessica Palmer spends time using her art to support wetland habitats, particularly with marshes. A combination of collage and paint are what express her support of environmentalism around the cities of Bath and London. Most notably, the collage works in Waterfields are a celebration of marshes and wetlands showcasing flora and fauna of her local area. Palmer also uses her papercut creations to provide intricate depictions of wetland wildlife at its finest. Having worked with the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust and Forest of Imagination there seems to be more to come from the layers and landscapes of this artist.

Ever heard of the Bayou Bienvenue Wetland Triangle? Well, self-taught naturalist and artist John Taylor has spent his entire life in the wetland system located in the Lower 9th Ward of New Orleans. Coastal Louisiana is made up of millions of acres of wetlands built over thousands of years by the Mississippi River. Unfortunately, Taylor has seen almost 400 acres of freshwater cypress-tupelo swamp become ghost swamp, and has witnessed catastrophic weather events in his community over the last 60 years. Photography, wood carving, and spoken word are John’s mediums of choice to create a platform to showcase the impacts of coastal Louisiana’s land loss. Though recently he has partnered with the National Wildlife Federation, Taylor is a lifelong advocate for wetland restoration plus a storyteller to visitors and locals alike.

Our last artist not only deals in massive works, but combines environmental activism with education. Based in New York, Mary Mattingly is an interdisciplinary artist who creates submerged buildings, sculptural watershed ecosystems, and even edible barges (yes, free floating food). Many of her art installations are centered around water resources and span over the last 20 years of the climate crisis. A notable floating sculpture, WetLand, integrates nature and a hand-built environment with importance of an equitable and sustainable water system. No medium is left unused with Mattingly as she offers specific yet Avant-garde solutions to environmental problems. With some works taking years in the making, her large-scale projects represent issues in climate change, sustainability, and human impact.

Being able to interact with all spectrums of nature gives us the ability to increase our connection to it. Artists and scientists alike can help us notice things in nature that we previously had not understood or were never taught to see. Through this collaboration of the arts and sciences, more space is made to change people’s values of wetland resources. Start Googling, see what’s happening at your local art league; be a part of another pathway towards preservation or action. After all, not all wetland warriors have to wear hip waders and carry a clipboard.

Written on: September 26th, 2022 in Wetland Animals

By Kayla Clauson, DNREC’s Watershed Assessment and Management Section

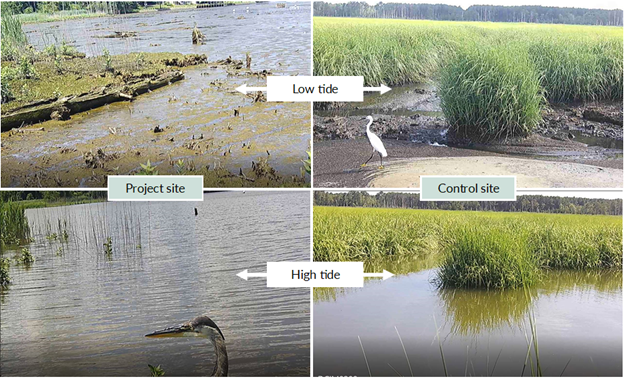

Wildlife cameras are a tool that scientists can use to collect wildlife field data. Discussed previously in a past blog post, wildlife cameras allow scientists to collect field data secretly, without being there, round the clock. This wildlife habitat utilization monitoring is part of a salt marsh recreation project, and supplements other ongoing monitoring that includes nekton sampling, breeding songbird surveys, vegetation, and wetland stability monitoring. Data collection for the project actually takes place within two Delaware salt marshes. One of the sites is where restoration will occur, in which we aim to rebuild a salt marsh where one used to exist. The other site is a healthy marsh and acts as a control. Scientists want to study the changes in habitat and wildlife utilization between both the sites and track any changes that may occur over time at the restoration site.

Each wetland experiences a semidiurnal tide, undergoing two high tides and two low tides daily. The animals that utilize these areas vary depending on time of day as well as the tides. See some differences between high and low tide at both sites below:

Family: Canidae – Fox and Coyote

Although secretive and swift, we’ve captured canids on our wildlife cameras. Canids are mainly nocturnal, and typically are seen during low tides that occur overnight and/or early mornings before sunrise. Two specific canids we’ve witnessed are Eastern Coyote (Canis latrans) and Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes). Because night-time shots are black and white, there are challenges when identifying these animals that have similar features. With assistance from specialized biologists, we were able to identify some of the canids as being the less-common coyotes. Coyotes are only present at our study site. The majority of the canid-captures are red fox. We’ve been fortunate enough to capture persistent interactions between a nesting Canada goose pair and a red fox (If you remember my previous blog post, Honk and Tonk had their work cut out for them defending their nest!). Red fox is present at both salt marshes.

Family: Procyonidae – Raccoon

These furry foragers are seen during similar times as the canids – coming out to eat at night during low tides. Raccoons (Procyon lotor) are omnivorous, eating both plants and animals. They can easily forage for food due to their very functional hands. In the salt marsh they are seen mainly feasting on crabs, shrimp, and fish they catch in the shallow low tide waters. If you observe the pictures closely, you can see how muddy the raccoon gets while walking around foraging in the mud. Raccoon have been seen at both our salt marshes.

Family: Cervidae – White-tailed Deer

Commonly seen on the side of the road grazing on grass, white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) often frequent the marsh for food. If you are confused how a deer gets to a more remote part of a marsh, you’ll be surprised to know that they are great swimmers! They are indeed very strong swimmers and have been recorded swimming up to 10 miles at a time. Young bucks and females have been spotted on our camera traps, utilizing both of our salt marshes. We were also lucky enough to see a rare piebald deer, with white and brown markings on her body. Piebaldism is a genetic condition that is expressed in about 2% of the white-tailed deer population- a pleasant find on our camera traps!

Family: Cricetidae – Muskrat

A semi-aquatic rodent, the muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) is often seen swimming or foraging within salt marsh waters. Although muskrat and beaver look similar, live in Delaware, and are both large rodents, they are not closely related. Muskrats are actually in a family with hamsters, voles, mice and rats, not beaver (family Castoridae). Muskrat can be seen at all times of day but have been captured mainly during nighttime.

Family: Mustelidae – Otter

More commonly found in lakes, rivers, and other freshwater wetlands, the North American River Otter (Lontra canadensis) has made an appearance at both of our study sites. There have been a pair of otter swimming and running in our tidal salt marshes. Another mainly nocturnal animal, otter was only captured in night time shots. Since otter are agile on both land and water, they’ve been seen both at high and low tides.

Other Mentions -Turtles and Tides

Although mammals and birds are the targeted species for this monitoring, there are other data that can be utilized from the cameras. For example, we can see the various turtle species enjoying our marshes as well. With the warming weather, turtles such as the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) and the common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) have been spotted more and more frequently basking in the sun or enjoying a swim.

Cameras also provide insight to other important factors, such as vegetation growth, storm occurrences, and tidal range. Observing vegetation is a standard monitoring technique used in our tidal wetland assessments, so capturing photos that show vegetation growth over the year is helpful to gain insight to how the habitat changes. Lastly, we’ve captured the salt marsh providing one of its important ecological functions- by withstanding storms and protecting our uplands from flooding. We’ve captured large waves battering our marshes as well as excess water standing over the marsh following a storm.

Written on: September 26th, 2022 in Education and Outreach

By Ivette Clayton and Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Tax Ditch Program

What is a Tax Ditch?

Did you know that there are 234 tax ditch organizations across the state of Delaware? They make up approximately 2,000 miles of channels across Kent, New Castle, and Sussex Counties. However, not all ditches are tax ditches.

A tax ditch is an organization that is a governmental subdivision of the state. It is watershed-based and formed and run by the landowners who live within it. Each organization is provided technical and administrative assistance by DNREC’s Tax Ditch Program and county conservation districts.

Tax ditch watersheds range in size from a small two-acre system to the largest 56,000 acre system. The design of a tax ditch varies with most having a “u” or “v” shape. Some are big and some are small, but all have a permanent right-of-way to allow access and disposal for maintenance activities. Visit de.gov/taxditchmap to see if your property has a tax ditch located near it!

Why Tax Ditches?

Just about everyone benefits, either directly or indirectly, from tax ditches. It equates to just over 100,000 people and almost one-half of the state-maintained roads. The best part, tax ditch organizations are set up so that the landowners within the watershed are the ones making maintenance decisions. Who knows the land better than the folks living right there?

It should be noted that to have a successful tax ditch organization and operational drainage, active participation by the landowners is required. Volunteer positions, such as the Chairman, Manager and Secretary-Treasurer, need to be voted in annually, and appropriate tax rates levied to the landowners to ensure proper maintenance can be conducted.

Are you interested in volunteering your time as an officer? First, you have to be a landowner within the tax ditch organization you are interested in participating with. Second, reach out to our office at DNREC_Drainage@delaware.gov, and we’ll get back to you with more information!

Changing Environment, Changing Designs

Most of Delaware is flat with a high-water table so tax ditches were created to assist in moving normal water flows off lands. Most tax ditches were created from 1950 to the late 1980s, and land use has greatly changed since then. To account for this land use change, to have more resilient ditches, and to improve the health of our waters, tax ditch design changes are occurring.

Floodplain Benches

Floodplain or bankfull benches are becoming a method to address erosion issues and improve the stability of tax ditches. Instead of being a “u” or “v” shape, it opens the slope of the tax ditch channel. This nature-inspired design allows the ditch to hold larger volumes of water while maintaining the integrity of the bank. The shallower channel reduces the water’s velocity. A slower current deters the water from acting like a knife and cutting deep into the land, eroding the banks away. Slower water flow also allows sediment to settle out of the water, improving water clarity and quality.

Design updates to tax ditches like this improve wetlands and water quality but do require adjustments to the Right-of-Ways (ROWs) that run along side the tax ditches, as well as other properties in the watershed. By expanding the width of the tax ditch, it pushes the ROWs further into the adjacent land. This can cause changes on the land used and requires coordination with landowners.

Below is a cross-section of a tax ditch without and with a floodplain bench.

Below is an example of a floodplain bench that was installed in the Hudson Road Tax Ditch.

DNREC’s Drainage Program’s hope to help tax ditch organizations plan and construct stream restoration projects like this one to address maintenance issues in the future.

Written on: September 26th, 2022 in Wetland Assessments

By Alison Rogerson, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Over the past year plus I’ve written five blogs sharing the results of our 2007-2017 Status and Trends report which reviews many angles of Delaware’s wetlands based on analysis of the 2017 Statewide Wetland Mapping Project (SWMP). In this post I am focusing on final thoughts and discussion of everything presented. It’s a lot of information to boil down, so based on everything we found with wetland acreage, gains, losses, and changes what are the key takeaways?

Tidal Wetlands

On the tidal wetland front, net losses were around 100 acres and mostly due to environmental forces such as erosion and sea level rise, mostly in the Delaware Bay. This is similar to findings from 1992-2007. We documented a lot of tidal fresh wetlands becoming tidal as salt water lines creep higher and higher up tributaries, changing the wetland community over time. This shifting upstream of tidal fresh wetlands is vital to their survival and is only possible when tributaries are free flowing and not blocked by dams and control structures.

We also documented some tidal wetland gains as a result of marsh migration inland. This is a good sign that wetlands are attempting to seek new territory as sea levels rise. However, marsh migration only works if the wetland to upland border is not built up with berms or hardened by structures such as roads and bulkhead. This requires planning ahead and leaving room. Fingers crossed that wetlands can migrate as fast as sea level rise is coming behind them.

Not too bad so far, right? The more concerning discovery was that a significant portion of tidal wetland changes (65%) were due to vegetated wetlands turning into basically mudflats. They have not yet washed away into open water habitat but without communities of Spartina and other grasses their capacity to function drops way down. The next step here is being washed away completely so resilient shoreline stabilization tactics become very important to prevent future erosion and loss. We can’t stop sea level rise but we can slow down the impacts.

Lastly, improved mapping technology allowed us to label tidal wetland areas that were dominated by the invasive reed Phragmites australis. This feature allowed us to identify that over half (52%) of all high marsh areas in tidal wetlands contained or were dominated by Phragmites. Phragmites preys on recently disturbed areas, areas with altered water regimes and along the wetland to upland border. Once it takes over, it is very difficult to remove so prevention and control is crucial. This baseline reading will be useful to compare against in another 10 years.

Non-tidal Wetlands

On the non-tidal wetland front, the picture was definitely more bleak. Delaware logged a net loss of 2,534 acres of vegetated non-tidal wetlands between 2007 and 2017. Gross losses were even more. This is, again, on track with our findings from 1992-2007. The Chesapeake Bay basin bore the brunt of the losses, accounting for 62% of statewide totals even though the Chesapeake Bay basin makes up only 34% of statewide acreage.

Non-tidal wetland losses were associated with clearing for logging activities (54%), development (24%), and agriculture (19%). This pattern is consistent with non-tidal wetland losses from 1992-2007. A small portion were due to transportation and utility impacts (3%). Although timber harvesting is a renewable resource, impacts to wetland hydrology and habitat are significant and wetland function will take decades to become restored. Impacts to headwater forested wetlands were most common and leads to reduced ability to filter excess nutrients and pollutants from water moving through them.

Although the gross loss of non-tidal wetland loss was lessened by wetland gains, those gains were in the form of created stormwater ponds. In fact, 81% of non-tidal wetland gains were as unvegetated, open water retention ponds, usually in residential developments or on farms. Stormwater ponds offer severely reduced functions, providing limited wildlife habitat, water filtration and sediment retention services and are not an even trade for the loss of natural wetlands. Wetland creation should replace the impacted wetland type.

Changes for non-tidal wetlands were mostly (71%) related to a shift in cover types. For example from forested to scrub-shrub as a result of forestry clear cutting starting to recover or a scrub shrub area maturing into a forested wetland. Another portion of non-tidal wetlands (15%) changed from non-tidal to tidal fresh as the salt water lines creep further upstream and flooded conditions increase. This could cause forested wetlands to become emergent. Stands of dead trees in coastal areas, or ghost forests, are becoming a noticeable sign of salt water intrusion, sea level rise and a shift in forested communities.

At the end of the day, every wetland trend comes with an associated shift in wetland function. By far, Delaware lost more wetlands in ten years than were created and with those losses come a reduction in storm protection, erosion control, water filtration, water storage, fish and shellfish production, breeding bird habitat, and carbon sequestration. Created wetlands don’t provide comparable services and functions to natural wetlands and likely won’t for several decades. It is these long term functional impacts that we need to be thinking about in the next ten years and hopefully Delaware can break away from the trend of wetland losses that have been in place since the 1990’s and earlier. Small impacts here and there add up over decades and lead to a fractured resource network that cannot provide the valuable services that we expect to serve us for free.

Check back in December for the final post in this series focusing on what we do next with management recommendations.