Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: February 27th, 2019 in Education and Outreach

By Brittany Haywood, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Wetlands are a part of our everyday lives. They are in the landscape silently helping to control flood waters, clean our drinking waters and protect us from damaging storms. Knowing what wetlands are, where they are, how they work, and what can and can’t be done with them before property is purchased can save time and money in the long run. Read on to start your journey into Delaware’s wetland world.

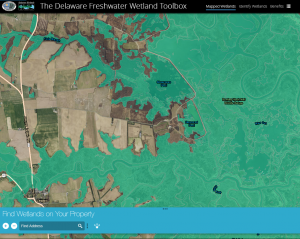

The first and easiest way to figure out if wetlands might be on a property is to look at maps. There are two different wetland map types available for anyone to use for free online. Each serves a different purpose. If there is an area on a property that seems like it should be a wetland, but it is not showing up on a map, you should probably have a wetland delineation performed.

Biological Wetland Maps

These maps outline all wetlands using the biological definition of wetlands: wetlands must have water on the surface for some part of the year, hydric soils and hydrophytic plants.

They map all wetland types including tidal and non-tidal wetlands, and serve only as a guidance tool. If a definitive wetland boundary needs to be determined, a wetland delineation is needed. Remember only certain wetland types are regulated, and just because a wetland is mapped, does not mean it is regulated. Click on one of the two maps below to get started:

The State-regulated Tidal Wetland Maps

The state of Delaware has the authority to regulate activities in tidal wetlands. Regulated wetlands are maintained at the Federal, state and county levels. These regulatory maps can help determine if there are State of Delaware regulated tidal wetlands on a property. If a landowner wants to know the location of State of Delaware jurisdictional features or believes the map to be incorrect, a Jurisdictional Determination and Map Change Request can be made.

What’s the Difference Between a Wetland Delineation and a Map?

A wetland delineation is a legal determination of a wetland boundary. An environmental consultant is hired to go onto a property and thoroughly document the existence of water, species of plants, and soil conditions to determine if a wetland is present and then flag its outer boundaries. These delineations can be used to see if a wetland permit is needed.

A wetland map is created through a computer analysis of environmental data and aerial images, and is followed up with on the ground verification of a select number of field sites. In the State of Delaware, every mapped location of wetlands has not been verified on the ground so these maps are only used for guidance purposes.

The Property has Wetlands, Now What?

Don’t run away screaming! Just because there are wetlands on a property, does not mean that the whole thing is unusable. Everyone wants a piece of land with a view, and wetlands can offer just that. Properties with wetlands are a wildlife watchers dream, have a built-in, no cost water purification system, offer drought protection, and can help reduce storm damage. Research has also supported the idea that healthy wetlands are good for maintaining underground water supplies (McCauley, 2015) which in turn can support crop growth on agricultural lands.

Wetlands are a prized natural resource. The best thing to do is to leave them alone, and give the wetland room to do its job. However if invasive plants, such as Phragmites australis, are a problem, some management of the plant maybe be beneficial to the health of the wetland and the property owner’s goals for the location.

You Want to Build Where?

Keep in mind, you don’t want to build on wetlands. Building on higher and dryer land will save you time and money in the long run. But if you have no other option, any activity that is planned on or near a wetland will most likely require a wetland delineation, mitigation plans that explain how wetland impacts have been minimized or are unavoidable, and permits or prior authorization at the Federal, state or county level.

Examples of activities that require permitting include filling of wetlands, removal of the buffer around wetlands, site access through a wetland, removing plants or tree stumps in a wetland or any sort of digging, construction or ditching in a wetland or stream. Basically, any action you do that alters the landscape of a wetland or stream needs a permit or authorization from at least one governmental agency.

Resources on Wetland Permitting and Regulations

Think of wetland maps and regulations as tools to help clients invest in the best locations to build on a property with high and dry land and ensure their investment can stand the test of time. Thanks for your interest in Delaware’s wetlands! If you are interested in learning even more, visit de.gov/wetlandtoolbox.