Facebook Twitter Instagram YouTube

Written on: March 7th, 2018 in Wetland Assessments

By Erin Dorest, DNREC’s Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

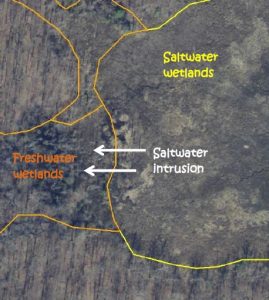

As you might imagine, sea level rise can increase water levels and cause more flooding. As that happens, salt water starts to move further inland. It may start to creep into freshwater areas through a process called saltwater intrusion. Higher waters can endanger coastal communities, while saltwater intrusion can affect our drinking water and agricultural lands. But we, WMAP, are also looking at the issue from our wetlands lens. How can sea level rise—and in turn saltwater intrusion—impact freshwater wetland habitats?

Freshwater wetlands that are located near saltwater wetlands will likely be some of the first areas to experience saltwater intrusion and increased flooding. If these wetlands begin to experience the effects of sea level rise, there are several possible outcomes:

We want to know which of these scenarios is happening to freshwater wetlands in Delaware!

Methods

To try to answer this question, we chose 15 study sites throughout Delaware where freshwater wetlands are next to saltwater wetlands. Those are the areas where we are most likely to see increased flooding and/or saltwater intrusion from rising sea levels.

We selected sites by comparing old and current state wetland maps. This allowed us to see where parts of freshwater wetlands may have started experiencing change. We also used old and current aerial imagery to select sites. Aerial imagery allowed us to see where vegetation changes, such as tree or shrub death, have begun to occur. We placed four sampling points at each field site in order to best describe the whole area that might be in transition. At each point for each site, we gathered data about water salinity, vegetation, and soils.

Field Results

What we have seen so far is that there are quite a few standing dead trees along edges of many forests that are next to saltmarshes. This shows that some forest edges are starting to die off as they face increased flooding and/or saltwater intrusion, as we expected. We have also seen that the common reed is moving into a lot of these areas where trees are dying off. This suggests that invasive Phragmites is colonizing areas before native saltmarsh plants have a chance to.

A lot of our fieldwork for this study was done in the 2017 field season, but we will be finishing up in the 2018 field season. Stay tuned for more detailed results and our conclusions!

Written on: March 7th, 2018 in Wetland Assessments

By Kenny Smith, DNREC, Wetland Monitoring and Assessment Program

Wetlands provide many vital benefits to the State of Delaware, like habitat for all kinds of plants and animals, improved water quality, and erosion control. Another benefit that wetlands provide is flood control. Wetlands have the ability to collect and store storm waters and lessen flooding down river, and we are working on a project to study just that.

Riverine Wetlands

No matter where you are in Delaware, there is at least one wetland located within a mile of you. Wetlands do not always have water at the surface. For this reason, we determined a wetland to be an area where water is held in the top 12 inches of the soil or higher for two or more weeks. This particular project focused on riverine or floodplain wetlands. Riverine wetlands are found along non-tidal creeks or rivers surrounding the banks of the creek. One of their main benefits is that they absorb and hold onto any excess water in the system. Creeks and rivers without wetlands along them can have significant damage or erosion to nearby properties from storm events.

Monitoring Water Levels in Riverine Wetlands

Our program, WMAP, installed three wells in an area along the Blackbird Creek in the Blackbird Forest in 2015. We placed the wells throughout the riverine wetland to figure out what the water in the soil is doing at the site to then determine how much flood protection that particular wetland can provide. The wells collect data on how much and often the wetland is soaked with water. Every four months we go back to the site to download the data and do any maintenance.

Does the Blackbird Forest Wetland Offer Flood Protection? And How Long was the Wetland Wet?

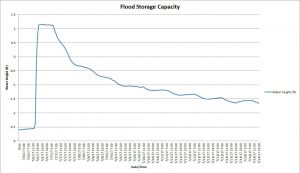

The 2016 data showed that this particular wetland had water in the top 12 inches of the soil or higher for for about 179 days throughout the year (if you combine the days together, that is almost six months)! The water level was even above the ground surface on four different days. Looking at what months were the wettest, the data also showed that the majority of the water was held for 162 days from December 15, 2015 to May 27, 2016. This information supports the fact that wetlands hold more water in the winter and early spring months.

Can the Wetland Soak Up Water?

To figure out how much flood protection the Blackbird Forest riverine wetland provided, we compared the water depth of our wells with a downstream water level gauge in the creek. The thought process is that as precipitation falls the creek water level will rise. Once it has rained, snowed, or sleeted enough, the water level will reach the creek banks and overflow into the wetland. Then, the wells should show the increase of water in this wetland.

We have had a few large precipitation events since we installed these wells and can visualize how much water these wetlands can hold in these events. One example of this was around December 25, 2015. The site received about two inches of precipitation and in response the creek water gauge increased by 27 inches and our well water levels increased by 19 inches. Another example was on July 6, 2017. The site received approximately seven and a half inches of precipitation, the creek water gauge rose to almost 33 inches above the normal level and our wells reported an increase in 45 inches.

Can the Wetland Slowly Release the Water?

The well data also showed that this wetland surrounding the creek was able to quickly soak up the overbank flooding and slowly release it. The water level in the wells usually increased exponentially faster than decreased after the precipitation events. If the wetland hadn’t been there, it is likely the water would have quickly rushed down creek causing flooding or erosion damage in both of these rain events.

Future Monitoring Efforts

We will continue to monitor our Blackbird Forest site to further explain the function of riverine wetlands to the landscape. In addition, we also have three wells in a flat wetland in the Ted Harvey Wildlife area in Dover, DE where we have been collecting data. Here we will look at the relationship between flat wetlands and precipitation.

Want more information about this project? Contact kenneth.e.smith@delaware.gov or 302-739-9939.